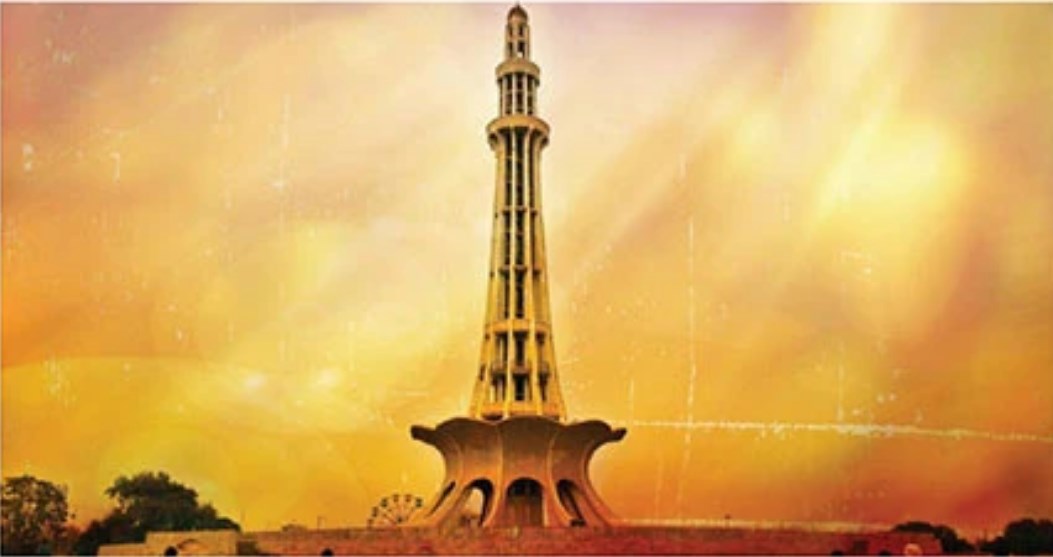

The promise of

23rd March

What was the 23rd March Resolution? What was its political context? What is its current state of affairs and relevance? What does it demand from the present day Pakistan? These are some of the questions pondered in this article albeit very briefly. Empirically, it happened at the Lahore Session of All-India Muslim League on March 22nd-24th, 1940. Along with other relevant matters, the Session categorically rejected the scheme of federation embodied in the Government of India Act, 1935 as being “unsuited to, and unworkable for Muslim India”. It empathetically demanded a new constitution for the protection of minorities rights pertaining to their religious, cultural, economic, political, administrative and other rights. To put it differently, the Muslims of India demanded “adequate, effective and mandatory safeguards” for their (minority) group rights.

The case for Muslim homeland was well substantiated by M A Jinnah in an article in the London Weekly Time & Tide on March 9, 1940 in the following words:

“Democratic systems based on the concept of homogeneous nation such as England are very definitely not applicable to heterogeneous countries such as India.... If, therefore, it is accepted that there is in India a major and a minor nation, it follows that a parliamentary system based on the majority principle must inevitably mean the rule of major nation”.

Jinnah’s ideas were supplemented by hard and undeniable facts too. It was explicit from the attacks on the Muslims since the Congress led provincial government in India. The following words shed light on how Jinnah very aptly pointed the systematic and gross activities of Hindu majority against the Muslim minority since 1935:

“In the five Muslim provinces every attempt was made to defeat the Muslim-led-coalition Ministries. Attempts were made to have Bande Mataram, the Congress Party song, recognised as the national anthem, the Party flag, and the real national language, Urdu, supplanted by Hindi. Everywhere oppression commenced and complaints poured in such force. Is it the desire (of British people) that India should become a totalitarian Hindu State? And I feel certain that Muslim India will never submit to such a position and will be forced to resist it with every means in their power. To conclude, a constitution must be evolved that recognises that there are in India two nations who both must share the governance of their common motherland.”

Against the above pretext, it is crystal clear that Jinnah and his companions wanted to win constitutional arrangements to avoid the continuing persecutions of the Indian Muslims in the near future. Since then, it became evident that All India Muslim League wanted to secure the rights of the Indian Muslims and was not possible constitutional recognition of two separate nations living in one state and consequently, required likewise appreciation by their colonial masters.

Under their continuous struggle, Jinnah and his counterparts won a separate home for the Indian Muslims. In his first speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, Jinnah as the father of the nation, promised a set of rights for the citizens of the newly born state on August 11, 1947.

He emphasised on an inclusive and impartial government, religious freedom, rule of law and equality for all. Jinnah also outlined a list of urgent problems to be fixed by the new government. To name a few, his list included law and order, so life, property and religious beliefs are protected for all. He also referred to the problems of bribery, black-marketing and nepotism. Most importantly, he visualised that all citizens of the country must be “first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights”. But did we win Jinnah’s resolve of freedom and other human rights? Nation’s history tells us rather a very different story.

Unfortunately, the group rights promised by the founding fathers of Pakistan were never translated into reality. The human rights conditions become even more gruesome over time. Furthermore, human rights listed in the International Bill of Human Rights as well as the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan hardly touched the social, political, economic and cultural ontology of Pakistan. Interestingly though, in the name of group rights the state became increasingly powerful whereas the individuals as powerless. The irony of the matter is that the state itself is grounded in the collective rights of individuals in order to dispense their rights as a duty bearer but it turned out to impede the realisation of its very purpose.

As Pakistan is celebrating the 81st anniversary of its “Resolution” at the national level, it is high time to ponder upon certain questions. First, do we need to comprehend the real meanings of an independent sovereign state where the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of its citizens come on top of everything else?

Second, what is the use of state if it consistently fails to deliver its fundamental promise to its people? Third, what if there appears a clear clash of interests between civilians and state institutions where later assumes itself above public accountability and scrutiny? Fourth, what if leaders elected by the public to serve them involve themselves in nepotism, bribery, corruption and looting and plundering of public funds? Lastly, what if ethnic and religious minorities consistently whine against the organized violation of their rights?

The current history of the world enlightens us that when group right namely state sovereignty endangers the basic rights and interests of individuals, it should not be considered as a genuine human right. Therefore, there must not be any compromise on individuals’ rights in whatsoever conditions and by whosoever be it any state or regime. Hence, we need to think about the way out of the quagmire which has encircled the people of Pakistan since their dream of freedom has partially realized.

To begin with, all states are supposed to respect the human rights of their citizens. For example, after basic rights, equal importance must be given to freedom of speech, association, assembly and there must not be any form of torture, disappearance, and mass killings in an organised fashion.

Some states do cross the ethical and legal threshold by referring to the group right of self-determination as well as on the basis of rationalism. Their constructs include one or all of these justifications: a) the perceived benefits of repressing exceed the costs,

b) there are no viable alternatives for socio-political control, c) the probability of success from repressive action is high, d) utilitarian use of force, e) to end the specific violation. These arguments which are sometimes termed as the utilitarian approach is vehemently debated and challenged in the moral discourses hence do not warrant the violation of human rights by any state.

Arguably, it is also a considerable fact that as an infant democracy, a state may go for political repression to establish order to advance economic goals/prosperity. Therefore, it is assumed that as state repression decreases as democratic maturity (values) increases. Likewise, all democracies are not the same therefore, insistence on one specific form of democratic values and practices may go against the spirit of democracy. Nevertheless, the aforementioned excuses are losing their moral grounds in the case of Pakistan as the state is almost approaching its seventy fifth anniversary and the Declaration its 81st. Today, we must reinvert the real promise of Pakistan.

The secret to realising the Promise of Pakistan is hidden in true democracy as more and more democracy leads to less and less state coercion as it provides the safest route to people to vote the highest authorities out of office if voters find their actions inappropriate and contrary to the promise of the constitution. Along the same lines, democratic values dictate the democratic behaviour of state officials. Lastly, democracy gives a way to alternative perspectives, tolerate dissent, breeds an environment for national dialogue, and reconciliation which today’s Pakistan needs most. Let us rediscover the promise of the Pakistan Resolution and make our country a truly social welfare democracy.

– The writer teaches International Relations at Iqra

University Islamabad. He can be reached at:

tasawar.hussain@iqraisb.edu.pk

-

Kate Middleton Shares Moving Message For Cancer Patients

Kate Middleton Shares Moving Message For Cancer Patients -

Gigi Hadid Battles Heartache After Zayn Malik's Brutal Love Confession

Gigi Hadid Battles Heartache After Zayn Malik's Brutal Love Confession -

Ernie Anastos Dies Of Pneumonia After Urging People To Stand Up For Truth In Last Message

Ernie Anastos Dies Of Pneumonia After Urging People To Stand Up For Truth In Last Message -

Gigi Hadid Cannot Help But Wish The Best For Ex Zayn Malik

Gigi Hadid Cannot Help But Wish The Best For Ex Zayn Malik -

Kate Middleton To Attend St Patrick's Day Parade

Kate Middleton To Attend St Patrick's Day Parade -

Uber Partners With Motional To Launch Commercial 'robotaxis' In Las Vegas In Latest Technology Push

Uber Partners With Motional To Launch Commercial 'robotaxis' In Las Vegas In Latest Technology Push -

No Respite For Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor As New Photo With Epstein Emerges

No Respite For Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor As New Photo With Epstein Emerges -

Royal Expert Reveals Meghan Markle, Prince Harry 'new Strategy' With Australia Tour

Royal Expert Reveals Meghan Markle, Prince Harry 'new Strategy' With Australia Tour -

Jack Harlow Shares Rare Insight Into His Dating Life

Jack Harlow Shares Rare Insight Into His Dating Life -

Ahead Of Harry And Meghan's Visit, King And Queen Leave For Australia

Ahead Of Harry And Meghan's Visit, King And Queen Leave For Australia -

Kim Kardashian, Kendall Jenner Clash Over Lewis Hamilton?

Kim Kardashian, Kendall Jenner Clash Over Lewis Hamilton? -

Adobe To Pay $75m To Settle US Lawsuit Over Hidden Charges

Adobe To Pay $75m To Settle US Lawsuit Over Hidden Charges -

Stephanie Buttermore Fans Continue To Raise Big Question

Stephanie Buttermore Fans Continue To Raise Big Question -

Bobbi Althoff Reveals Where She Stands With Ex Cory After Shocking Split

Bobbi Althoff Reveals Where She Stands With Ex Cory After Shocking Split -

AI Adds To Employee Workload, Study Finds

AI Adds To Employee Workload, Study Finds -

'KPop Demon Hunters' Sequel: Here's What We Know So Far

'KPop Demon Hunters' Sequel: Here's What We Know So Far