South Asia’s gender map

This year’s score marks second consecutive drop from Pakistan’s best score of 57.7% achieved in 2023

The World Economic Forum has released the Global Gender Parity Index 2025. Pakistan ranks at 148th, the last position on the index.

Pakistan’s overall gender parity score has slightly declined from 57 per cent to 56.7 per cent. Since 2006, the country has made only a 2.3 percentage point improvement in closing the gender gap. This year’s score marks the second consecutive drop from Pakistan’s best score of 57.7 per cent achieved in 2023. There has been a -1.3 percentage point decline in economic participation and opportunity for women.

Although women’s economic representation indicators have stayed the same, income disparity has slightly increased (+0.02 points), and perceived wage inequality has risen by 4.0 percentage points. The only area where Pakistan made progress is educational attainment, bumping educational parity upwards by +1.5 percentage points to reach 85.1 per cent. This improvement is mainly due to an increase in female literacy (from 46.5 per cent to 48.5 per cent), but also because male enrolment in higher education has dropped, which narrows the gap but reduces overall educational reach. While women’s representation in parliament increased slightly by 1.2 percentage points, the share of women ministers fell from 5.9 per cent to zero in 2025, which brought down the overall political empowerment score.

India ranks 131st on the Global Gender Parity Index 2025, with an overall score of 64.4 per cent. This is three places lower than in 2024, mainly because other countries have done better. India’s score in Economic Participation and Opportunity has improved by 0.9 points, now at 40.7 per cent. Most indicators stayed the same, but women’s estimated earned income rose from 28.6 per cent to 29.9 per cent, which helped improve the score.

The labour force participation rate remains at 45.9 per cent, matching India’s best level so far. In education, India scores 97.1 per cent. This comes from better female literacy and more women enrolling in higher education. The health and survival parity has also improved, despite both men and women now living slightly shorter lives.

Political empowerment saw a small drop of 0.6 points. Women in parliament fell from 14.7 per cent to 13.8 per cent, and women ministers fell from 6.5 per cent to 5.6 per cent. This brings the indicator down to 5.9 per cent, far below its best level of 30 per cent in 2019.

The biggest surprise in the 2025 Global Gender Parity Index is Bangladesh. Despite facing turmoil last year, Bangladesh is doing wonders and has made remarkable progress. It now ranks 24th, the largest jump in the global gender parity gap ranking in a single year, climbing 75 places. Its overall gender parity score has increased significantly from 68.9 per cent in 2024 to 77.5 per cent in 2025.

The main reason for this progress is political empowerment. The share of women in ministerial positions rose sharply from 9.1 per cent to 22.2 per cent between 2024 and 2025. Bangladesh now ranks first in South Asia and third globally in political parity. Economic participation and opportunity is another driver of this improvement, mainly because of updated labour-force data that brings Bangladesh’s economic parity back to its 2023 level.

Bangladesh has also made gains in closing the gender gap in literacy, with women catching up to men. In South Asia, Bangladesh leads the region, Bhutan is ranked 119th with 0.663, followed by Nepal at 125th with 0.648. Sri Lanka stands at 130th with 0.645, and India at 131st with 0.644. Maldives is ranked 138th with 0.626. The contrast between Bangladesh and Pakistan is striking. In political empowerment, Bangladesh ranks third globally, while Pakistan is at 118. In economic participation, Bangladesh stands at 141, compared to Pakistan at 147. In educational attainment, Bangladesh is at 115, while Pakistan is at 137. And in health and survival, Bangladesh ranks 123, ahead of Pakistan at 131.

Only in Bangladesh do women represent around one-fifth of ministers (18.2 per cent). Pakistan has scored 0.1 almost zero for women’s ministerial involvement in the Global Gender Gap Report 2025 on 0-1 scale, this figure reflects a reality we are reluctant to face. On paper, we can cite a federal minister for women, a state minister and the historic election of Pakistan’s first woman chief minister in Punjab. Balochistan and Sindh each count a single woman in their cabinets, while Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has none. Yet these scattered examples are exceptions rather than the rule – isolated dots on a map that, when viewed from a distance, still resemble an empty landscape.

The National Commission on the Status of Women (NCSW) has rejected these findings, calling the data unreliable and unreflective of reality. The commission has also strongly criticised the score for women’s ministerial involvement, arguing that it overlooks the ground-level progress made in political representation. The report’s score does not undermine these individual achievements, but we should keep in mind that token representation cannot be a substitute for meaningful inclusion.

Gender disparity means having equal numbers of women and men in different areas of life like education, jobs, politics and leadership roles. It’s about making sure both genders are represented in the same proportion. For example, gender parity at work means women and men are equally present at all levels. It’s a way to measure balance using numbers. But while gender parity looks at equal numbers, gender equality goes a step further it focuses on fairness, removing barriers, and making sure everyone has an equal chance to succeed.

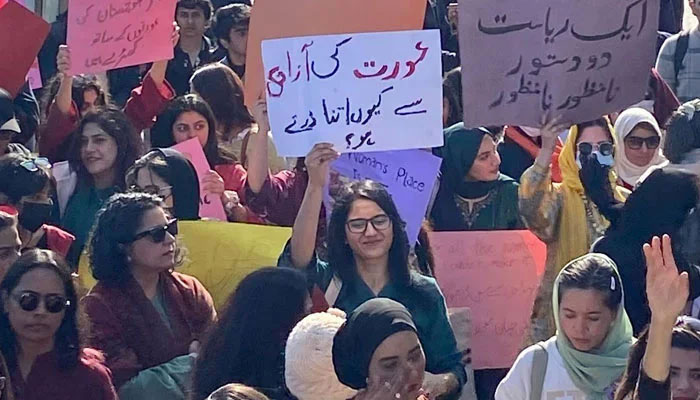

This Global Gender Parity Index is directly related to the policies and actions of governments. We may argue over its findings, challenge its methods or expose gaps in its data but we cannot, and must not, turn away from the harsh reality it reveals. We cannot shut our eyes, hoping the storm will pass. The truth is that the condition of women in Pakistan is a glaring injustice that demands action, not empty words. The situation for women in Pakistan is heartbreaking. Even today, in the 21st century, women are forced to fight for the most basic human rights, the right to education, the right to healthcare, the right to simply live with dignity.

And yet, whenever the concerns are raised, the same hollow reply echoes back: “But religion has given women all the rights”. Who is denying that? The problem is with our culture, our people and our society. If every human being is born with rights, why do men choose to rule over women and suppress them at every step of their lives? The relationship between a man and a woman should be built on trust, on respect, on shared strength not on power and control. There must be compatibility, not domination.

We don’t need to import or mirror the Western model of feminism. We have the power to carve our own way, a way that honours our values, our culture and our identity. But no path will appear until we open our eyes and our hearts to the reality, no progress will be made until we find, deep within us, the courage to question old mindsets, the resolve to unbind ourselves from the chains we have long accepted as normal, and the will to rise.

We can learn from Bangladesh, they chose not to stand still. They chose progress, they chose to rise and they are rising. Despite facing challenge after challenge, they moved forward, because they wanted to, because they dared to, because they understood that true prosperity begins with the will to change. We need to transform our attitudes and rethink our behaviours – before we are forced to face a truth too bitter to bear that perhaps the time when a daughter was buried at birth was less merciless than now, when we let her live only to bury her spirit, her hopes, her dignity, every single day.

The writer is professor and chairperson at the Department of Digital Media, University of the Punjab, Lahore – and a feminist at heart.

-

Jake Paul Criticizes Bad Bunny's Super Bowl LX Halftime Show: 'Fake American'

Jake Paul Criticizes Bad Bunny's Super Bowl LX Halftime Show: 'Fake American' -

Prince William Wants Uncle Andrew In Front Of Police: What To Expect Of Future King

Prince William Wants Uncle Andrew In Front Of Police: What To Expect Of Future King -

Antioxidants Found To Be Protective Agents Against Cognitive Decline

Antioxidants Found To Be Protective Agents Against Cognitive Decline -

Hong Kong Court Sentences Media Tycoon Jimmy Lai To 20-years: Full List Of Charges Explained

Hong Kong Court Sentences Media Tycoon Jimmy Lai To 20-years: Full List Of Charges Explained -

Coffee Reduces Cancer Risk, Research Suggests

Coffee Reduces Cancer Risk, Research Suggests -

Katie Price Defends Marriage To Lee Andrews After Receiving Multiple Warnings

Katie Price Defends Marriage To Lee Andrews After Receiving Multiple Warnings -

Seahawks Super Bowl Victory Parade 2026: Schedule, Route & Seattle Celebration Plans

Seahawks Super Bowl Victory Parade 2026: Schedule, Route & Seattle Celebration Plans -

Keto Diet Emerges As Key To Alzheimer's Cure

Keto Diet Emerges As Key To Alzheimer's Cure -

Chris Brown Reacts To Bad Bunny's Super Bowl LX Halftime Performance

Chris Brown Reacts To Bad Bunny's Super Bowl LX Halftime Performance -

Trump Passes Verdict On Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show

Trump Passes Verdict On Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show -

Super Bowl 2026 Live: Seahawks Defeat Patriots 29-13 To Win Super Bowl LX

Super Bowl 2026 Live: Seahawks Defeat Patriots 29-13 To Win Super Bowl LX -

Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton Make First Public Appearance As A Couple At Super Bowl 2026

Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton Make First Public Appearance As A Couple At Super Bowl 2026 -

Romeo And Cruz Beckham Subtly Roast Brooklyn With New Family Tattoos

Romeo And Cruz Beckham Subtly Roast Brooklyn With New Family Tattoos -

Meghan Markle Called Out For Unturthful Comment About Queen Curtsy

Meghan Markle Called Out For Unturthful Comment About Queen Curtsy -

Bad Bunny Headlines Super Bowl With Hits, Dancers And Celebrity Guests

Bad Bunny Headlines Super Bowl With Hits, Dancers And Celebrity Guests -

Insiders Weigh In On Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton's Relationship

Insiders Weigh In On Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton's Relationship