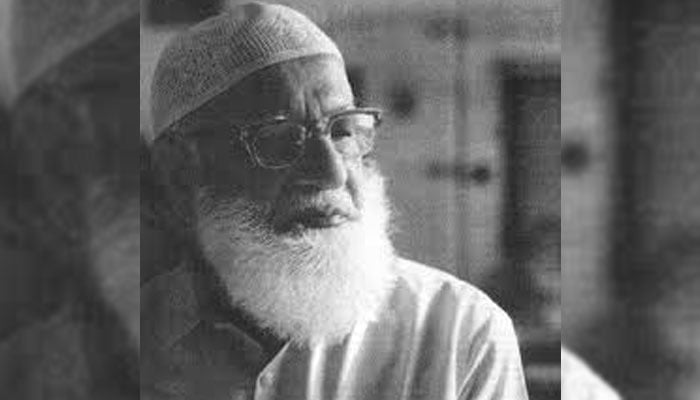

The works of Jamal Abro

Jamal was among the Sindhi short story writers who shaped landscape of Sindhi literature after 1947

The Sindhi short story is nearly a century old now. In the early decades of the 20th century, writers such as Mirza Qaleech Baig, Lalchand Amardinomal, and Jethmal Parsram started writing Sindhi short stories that exposed feudal lords and moneylenders as the main exploiters of the working classes in Sindh that was part of the Bombay presidency or province till 1936.

Gobind Punjabi’s book ‘Sard Ahoon’ (Sighs Full of Grief) is a landmark collection of short stories that appeared in 1940. Gobind Malhi is another name that adorned the firmament of Sindhi literature during the pre-partition decades. Amarlal Hingorani wrote his short story ‘Ado Abdur Rehman’ (Brother Abdul Rehman) in 1930 – published in 1940 – and Assanand Mamtora penned ‘Kiki’ (a pet name for a girl child) and ‘Gawarin’ (Rustic Woman). Unesco shortlisted both stories, ‘Ado Abdul Rehman’ and ‘Gawarin’ as part of their world heritage of literature. In the 1940s emerged Subho Gianchandani and Mangharam Malkani who ventured into criticism too.

Jamal Abro, born in 1924, was among that generation of Sindhi short story writers who shaped the landscape of Sindhi literature after 1947. He occupies an exalted place as one of the founders of Sindhi literature in the post-independence decades. His oeuvre does not span large tomes; he wrote sparingly but exceptionally well. In terms of the techniques and thoughts presented in his short stories, he was a trendsetter by all means. His experiences as a lawyer and judge enabled him to comprehend the problems of common people that he delineated in his unique style.

Abro proved himself to be a conscientious judge not only of the criminal cases presented to him but also of social injustices that the dominant classes meted out to the Sindhi folks. Anyone interested in the literature of Sindh simply cannot move forward without first reading Jamal Abro’s short stories. Some critics have called Abro an interesting blend of Maxim Gorky, Jack London and O’ Henry. This comparison appears to be off the mark as Abro wrote just 17 short stories and only a couple of essays, but in terms of style, he has some similarities with Gorky and London.

Jamal Abro began his literary journey in 1949 with his first short story ‘Hoo Hur Ho’ (He was a Hur). It is the story of a prominent Hur – Khairu Khaskheli – a follower of Pir Pagara. In the story, the British authorities had imprisoned the Pir and Khairu felt enraged at the incarceration of his revered spiritual leader. Sindh had become a battleground with attacks on railway carriages and target killings of British officers. The British army was bent upon crushing the rebellion with the proverbial ‘iron hand’. Villages come under fire and women were abducted and raped.

When Khairu became a leader of the armed struggle against the British, his mother and sister also became a target of the British army’s brutalities and were killed. The authorities hanged the Pir on charges of sedition and treason but that intensified the struggle; Khairu became a legendary freedom fighter against British rule. Dacoits and terrorists were the monikers attached to freedom fighters who also indulged in robberies and attacked the police at random and killed the collaborating landlords. After independence, Khairu continued his activities and played the role of Robin Hood, looting the rich and helping the poor.

‘Pirani’ is the story of a Brohi family climbing down the hills with their animals and meagre subsistence material on a couple of bullock carts. They are coming to Sindh to sell bamboo at throwaway prices. All family members are in tatters and barefoot, looking dirty and unshaven for weeks. Nine-year-old Pirani is so dear to her parents that they feed her their own share of the stale food they eat with water. Unable to earn any living, they end up selling Pirani to a local rich man. The story leaves you in a state of shock.

Pirani is arguably his best and most impactful story, and it catapulted Jamal Abro to the hall of fame in Sindhi literature. Abro beautifully describes family bondage in a nomadic family and then shows how compelled the father is to sell his daughter to an elderly but wealthy man. “They dragged the struggling girl inside her new home. But she was slipping away from their hands, kicking, biting, screaming, and bouncing like a rubber ball… The child’s delicate throat was hoarse with cries. Between tears and hiccups, she kept moaning for her father and mother in vain.” (Translation by Hasho Kevalramani)

‘Khamise jo Coat’ (The Coat of Khameeso) exposes the ugliness of a morbid society that Mashaikhs and Mirs shamelessly rule. Excessive religiosity and merciless poverty go hand in hand in this story of an 11-year-old barefoot child who wears a tattered coat with a dirty cotton-filled cap but has no shirt on his torso while tending his cattle herd in the village. The clergy is ruthless in exploiting the poor children. Then one day Khameeso falls sick and his parents can hardly afford a blessed thread from the local Mullah. Khameeso died, and the next day his younger brother Mahar takes charge of grazing the herd. He is wearing the same old tattered coat of Khameeso.

Another story ‘Badtameez’ (Discourteous) exposes the sham morality that has become a hallmark of society that thrives on hypocrisy. Those who are too courteous to the all-powerful bureaucracy become discourteous and even rude and ruthless to the poor and the powerless. An embodiment of moral rectitude in the face of power, maltreats the downtrodden. Economically depressed folk receive no courtesy even when they are on the verge of collapse.

‘Shah jo Phar’ (The Brat of a Shah) has an affable female character Maryam who is dynamic and loveable. But a farcical sense of racial superiority in a Syed (Shah) destroys her kind character. The story lays bare the religious conceit so prevalent in feudal and tribal societies across Pakistan. Maryam calls everyone mama (maternal uncle) and the villagers love her; giving her candies and biscuits. But one day when she calls a Shah her mama, he is so enraged that his wrath is unleashed on the poor girl.

‘Karo Munh’ (Blackened Face) is another story of abrasive shame in a decadent society that is more interested in tomb worship than feeding the poor. Mythical totems abound and innocent people like Deen Muhammad end up receiving severe punishments for stealing an anointed chador (floral wreath) spread over a sacred grave. Deen Muhammad is unable to pay forty rupees for his ailing son’s treatment and tries to steal the chador, which results in his public humiliation with a karo munh (blackened face). He is paraded around the village and mocked and jeered at by all and sundry.

Another interesting story is ‘Maan Mard’ (Macho Man) revolving around a scary fantasy with a unique plot in Sindhi fiction. Writing for women’s rights was not uncommon in Sindhi novels and stories even before Partition, but the way Jamal Abro has used an interesting plot to show injustices to women in Sindh is marvellous. A man is transported to a faraway land where women rule and men are subjected to the treatment that women receive in Sindh. With horrifying details of women’s ruthless treatment of men, Abro upends the equation.

Perhaps the longest and the most controversial story by Jamal Abro is ‘Pishoo Pasha’. It blends folk tales of dacoits with an ideological narrative that smacks of communist propaganda. Being a deeply religious man, Abro sympathized with the struggle of the poor; ‘Pishoo Pasha’ shows an armed insurrection against the state. Abro remains an icon in Sindhi short story writing. He died in 2004 at the age of 80.

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK. He tweets/posts @NaazirMahmood and can be reached at:

mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

-

Eric Dane's Girlfriend Janell Shirtcliff Pays Him Emotional Tribute After ALS Death

Eric Dane's Girlfriend Janell Shirtcliff Pays Him Emotional Tribute After ALS Death -

King Charles Faces ‘stuff Of The Nightmares’ Over Jarring Issue

King Charles Faces ‘stuff Of The Nightmares’ Over Jarring Issue -

Sarah Ferguson Has ‘no Remorse’ Over Jeffrey Epstein Friendship

Sarah Ferguson Has ‘no Remorse’ Over Jeffrey Epstein Friendship -

A$AP Rocky Throws Rihanna Surprise Birthday Dinner On Turning 38

A$AP Rocky Throws Rihanna Surprise Birthday Dinner On Turning 38 -

Andrew Jokes In Hold As BAFTA Welcomes Prince William

Andrew Jokes In Hold As BAFTA Welcomes Prince William -

Sam Levinson Donates $27K To Eric Dane Family Fund After Actor’s Death

Sam Levinson Donates $27K To Eric Dane Family Fund After Actor’s Death -

Savannah Guthrie Mother Case: Police Block Activist Mom Group Efforts To Search For Missing Nancy Over Permission Row

Savannah Guthrie Mother Case: Police Block Activist Mom Group Efforts To Search For Missing Nancy Over Permission Row -

Dove Cameron Calls '56 Days' Casting 'Hollywood Fever Dream'

Dove Cameron Calls '56 Days' Casting 'Hollywood Fever Dream' -

Prince William, Kate Middleton ‘carrying Weight’ Of Reputation In Epstein Scandal

Prince William, Kate Middleton ‘carrying Weight’ Of Reputation In Epstein Scandal -

Timothée Chalamet Compares 'Dune: Part Three' With Iconic Films 'Interstellar', 'The Dark Knight' & 'Apocalypse Now'

Timothée Chalamet Compares 'Dune: Part Three' With Iconic Films 'Interstellar', 'The Dark Knight' & 'Apocalypse Now' -

Little Mix Star Leigh-Anne Pinnock Talks About Protecting Her Children From Social Media

Little Mix Star Leigh-Anne Pinnock Talks About Protecting Her Children From Social Media -

Ghislaine Maxwell Is ‘fall Guy’ For Jeffrey Epstein, Claims Brother

Ghislaine Maxwell Is ‘fall Guy’ For Jeffrey Epstein, Claims Brother -

Timothee Chalamet Rejects Fame Linked To Kardashian Reality TV World While Dating Kylie Jenner

Timothee Chalamet Rejects Fame Linked To Kardashian Reality TV World While Dating Kylie Jenner -

Sarah Chalke Recalls Backlash To 'Roseanne' Casting

Sarah Chalke Recalls Backlash To 'Roseanne' Casting -

Pamela Anderson, David Hasselhoff's Return To Reimagined Version Of 'Baywatch' Confirmed By Star

Pamela Anderson, David Hasselhoff's Return To Reimagined Version Of 'Baywatch' Confirmed By Star -

Willie Colón, Salsa Legend, Dies At 75

Willie Colón, Salsa Legend, Dies At 75