In rising waters

The domestic-international gap [in the US] in perceptions is not quite as large on climate change as it was on the pandemic back in 2020. For instance, 39 percent of non-Americans surveyed by Pew in 2021 rated the US record on climate change as ‘good’. A much larger number of Americans, 49 percent, share that opinion. More troubling is the ideological gap in the United States, with 67 percent of those on the right and only 26 percent on the left thinking that the US record is good.

Such gaps in perception were on full display at the big climate confab that’s taking place in Glasgow. Last week, leaders gathered to make declarations while critics mobilized in the streets to decry the insufficiency of those efforts. This week, the negotiators try to transform the declarations into numbers.

A couple of those declarations look promising. A deal on beginning to reverse deforestation by 2030 would be a great step forward (of course, a similar agreement in 2014 would also have been a great step forward). A pact to cut methane levels by 30 percent by 2030 is certainly welcome, but the biggest sinners in this regard (India, Russia, and China) are not yet on board.

The assembled leaders agreed to what they have called the ‘Glasgow Breakthrough Agenda’ covering five sectors that account for half of all carbon emissions: power, road transport, steel, hydrogen, and agriculture. This collection of initiatives is meant to create 20 million jobs and increase global GDP by 4 percent over what it would otherwise be by 2030.

Deeply troubling in all of these declarations is the continued reliance on private finance to lead the way toward a carbon-neutral world, like the pledge from the captains of finance to push for cleaner technologies. Unfortunately, they are not making a comparable commitment to stop investing in fossil fuels.

Just as citizens of countries tend to view the climate policies of their own governments more favorably than outsiders do, the leaders of the international community generally have a self-congratulatory approach to their own efforts. Those on the outside of the Glasgow meetings, on the other hand, were harshly critical. “Blah, blah, blah,” said Greta Thunberg in one of her latest jeremiads against the insufficiency of response.

Let’s be clear: it’s not nothing.

Going into the Glasgow meeting, the cumulative impact of all the pledges countries have made to reduce their carbon emissions would have led to the world heating up to 2.1 degrees Celsius (over pre-industrial levels) by 2100. Factoring in the pledges made at Glasgow, according to the International Energy Agency, will bring down that number to 1.8 degrees.

It’s not the 1.5 degree-level that represents the consensus of scientists and activists who want to avoid the worst effects of climate change. But it’s also the first time that the international community has managed to get below the 2-degree mark, which was the upper level established by the Paris accords.

But wait, this analysis comes with a number of important asterisks.

First, despite all the fine words surrounding the Paris Accords, countries have largely not met the agreement’s voluntary limits. Five years after making those commitments, countries were on track to reduce carbon emissions by a mere 5.5 percent by 2030 compared to the minimum requirement of 40-50 percent.

That’s probably a generous estimate. According to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, meeting the Paris commitments would only result, by 2030, in a 1 percent reduction from 2010 levels.

Both estimates, in any case, are probably off because, as The Washington Post reports this week, the data is incomplete and sometimes falsified outright. Algeria hasn’t reported since 2000, Qatar since 2007, Iran since 2010, China since 2014, Libya and Taiwan since, well, never: in all, 45 countries haven’t reported data since 2009. No country claims the carbon emissions from international travel and shipping (more than a billion tons a year). Countries like Russia and Malaysia have subtracted carbon emissions from their balance sheets based on their forests, and sometimes those estimates bear little relationship to reality. Even the emissions they do report don’t line up with the estimates of independent assessments. According to the Post, as much as 13.3 billion tons of carbon each year goes unreported.

Compounding this problem is the so-called brown recovery. The modest reductions in carbon emissions that took place during the COVID-19 economic shutdowns are being obliterated by the burst of post-pandemic economic activity. The world could have built back better in a sustainable manner. Instead, it is building back brown.

So, let’s take another look at the IEA prediction of substantial progress after Glasgow. The UN’s own estimate, released this week, suggests that the combined reduction in global temperature as a result of the Glasgow pledges – given the failures to meet earlier commitments, the gaps in the data, and the current upsurge in post-pandemic emissions – will be a mere 0.1 degrees, not 0.3 degrees. And the world is heading not toward a 2.1-degree Celsius increase by the turn of the next century but 2.5 degrees.

So, the gap between perception and reality has some very dangerous consequences indeed.

To narrow that gap, activists will have to continue to push governments to do better. Individuals think they are doing enough, think that their governments are doing enough, and on the whole consider climate change to be somebody else’s problem. They have to be persuaded otherwise.

One of the great compromises – or grand delusions, if you prefer – at the heart of the Breakthrough Agenda is encapsulated in the phrase ‘green growth’. At Glasgow, the luminaries promise millions more jobs and a boost in global GDP. Political leaders are not in the business of taking things away from people, of promising belt-tightening, of Scrooging everyone’s Black Friday buying spree. At Glasgow, like pretty much everywhere else, politicians promised more jobs (green ones), more energy (the clean kind), more gadgets (like electric cars).

More, more, more has been humanity’s mantra for the last 150 years or so. It used to be only the watchword of the rich. The industrial revolution democratized the phrase.

The problem, however, is that the planet can no longer accommodate our collective voracity. There just isn’t enough stuff to go around.

Excerpted: ‘Climate of Delusion’

Counterpunch.org

-

Scott Baio Reacts To Sudden Death Of 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Jennifer Runyon

Scott Baio Reacts To Sudden Death Of 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Jennifer Runyon -

Emilia, James Van Der Beek's Daughter, Shares How To Fight Grief After Losing A Loved One

Emilia, James Van Der Beek's Daughter, Shares How To Fight Grief After Losing A Loved One -

Rihanna Shooter: Police Reveal Identity Of Singer's Home Shooting Suspect

Rihanna Shooter: Police Reveal Identity Of Singer's Home Shooting Suspect -

Dolly Parton Ready To Marry Again?

Dolly Parton Ready To Marry Again? -

Savannah Guthrie Breaks Cover As Search For Mom Nancy Intensifies

Savannah Guthrie Breaks Cover As Search For Mom Nancy Intensifies -

Jennifer Lopez Shares Emotional Post After Discussing Split With Marc Anthony

Jennifer Lopez Shares Emotional Post After Discussing Split With Marc Anthony -

Andrew's Escape Plan Just Hit Unexpected Roadblock: 'Huge Blow'

Andrew's Escape Plan Just Hit Unexpected Roadblock: 'Huge Blow' -

Jessica Alba And Danny Ramirez Send Strong Message: Ignore Joe Burrow Rumours

Jessica Alba And Danny Ramirez Send Strong Message: Ignore Joe Burrow Rumours -

Dakota Johnson Leaves Fans Speechless With Calvin Klein Ad

Dakota Johnson Leaves Fans Speechless With Calvin Klein Ad -

Stephanie Faracy Talks About Her Role In 'Nobody Wants This' Season 3

Stephanie Faracy Talks About Her Role In 'Nobody Wants This' Season 3 -

Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Receive Fresh Warning

Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Receive Fresh Warning -

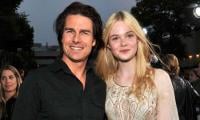

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards -

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer -

Paul Bettany Gets Honest About Voldemort Casting Rumours In 'Harry Potter' Series

Paul Bettany Gets Honest About Voldemort Casting Rumours In 'Harry Potter' Series -

Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner Show Support As Brody Jenner Reveals Big News

Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner Show Support As Brody Jenner Reveals Big News -

King Charles Plans Emotional Reunion With Lilibet, Archie

King Charles Plans Emotional Reunion With Lilibet, Archie