KU’s degrees may lose their uniqueness without Urdu calligraphy adornment

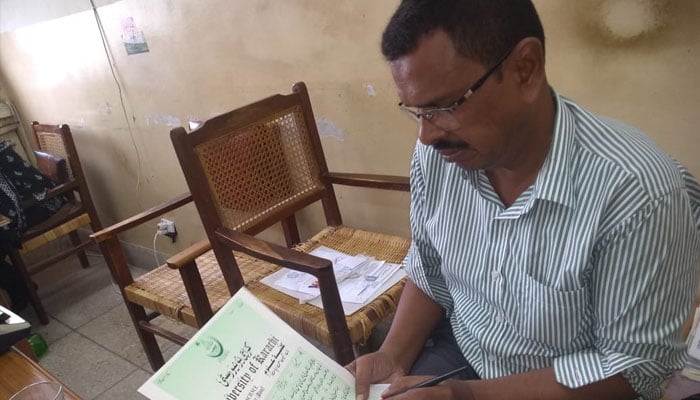

Piles of classified documents and other important records are stacked before Urdu calligraphers Amir Ilyas and Rehan Mustafa inside a busy office in the University of Karachi’s examination department.

They sit in a corner on a mattress placed over a wooden pallet. With pillows set against the wall behind them, they hold blank degrees in their laps to fill them in with students’ information.

To produce ornate text, they use fountain pens as well as cut-nib pens dipped in the inkwell placed in a box between the two men. They don’t have anything fancy at their disposal, such as swivel chairs with smooth castors, glossy office tables, bundles of white papers or marble pen holders. Instead, the chair next to their pallet is splintered and the wall behind them is stained.

As far as furniture is concerned, comfortable chairs or sturdy tables don’t help their penmanship at all, but rather make it difficult to create good work. “Sometimes we need to bend the paper, hold the pen at a certain angle, reposition our hands a lot to inscribe the words in the best possible way,” explains Ilyas.

While he had learnt calligraphy from his elder brother, Ilyas had never imagined working at KU. But in 1995 he read a vacancy announcement in the newspaper, applied for the calligrapher job and found that he met the required criteria.

Since then he’s been working at the university. For many years he wrote 30 to 35 degrees. “Now I write 70 to 72 degrees a day. I’ve been working for the past 25 years. It took a long time, but I’ve finally become used to writing more degrees.”

Mustafa, who has a BA degree, became a calligrapher when he was in year six. He’s been working with Ilyas since 2006 and now writes the same number of degrees as his senior colleague.

Work ethics

As soon as the two men reach the office, they get to work to meet their target. “We’re just a two-member team on whom KU’s entire degree production is dependent,” says Mustafa. “If we start participating in union or other activities, how will the university issue degrees?”

Moreover, they need to be very careful to avoid errors. “Sometimes departments and examiners send us incorrect names of candidates, final percentages or names of the degree programmes,” says Ilyas. “Before finalising a degree, one of us cross-checks it against the relevant documents.”

Challenges

They continuously write degrees that are then issued to graduates, but they themselves can’t pursue further education because they work for the degree-awarding and examination sections.

To study further, they need to leave the examination department, but KU management will not transfer them to another department because the university doesn’t have any other calligraphers.

“When a government employee gets a higher degree, they get a raise and other financial benefits and incentives,” says Mustafa, “but there’s no such opportunity for us here. I wish to get a master’s degree, but it won’t result in any financial benefits for me in this job.”

Moreover, sitting on a wooden pallet working for hours day in day out over the past many years has resulted in several health issues for the two men, like neck pain, backache and short-sightedness.

They say calligraphy involves painstaking work and the family of a calligrapher lives from hand to mouth. “My children don’t fancy my work. They’ve never wished to learn it,” says Ilyas. Mustafa also doesn’t suggest that kids learn calligraphy. “I know how I live because of it.”

Computerised degrees

KU is perhaps the only university in Pakistan that has calligraphers to write degrees. But due to the demand of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) and the lack of competent calligraphers, the university’s examination department is planning to issue computerised degrees.

Dr Syed Zafar Hussain, KU’s controller of examinations, said the university issues bilingual degrees. The English text is printed on the paper, while the calligraphers write the Urdu text, he added.

He said the examination department receives 400 to 500 applications a day for the issuance of degrees. He added that since the normal waiting period is three months, most of the applicants select the urgent (one month) or the most-urgent (two weeks) option.

Dr Hussain said that just two calligraphers can’t write more than 150 degrees a day. He said that writing a degree is somewhat different from the art of a common calligrapher.

“We’ve been looking for competent calligraphers for the past many years, but no one has been able to meet the criteria. Therefore, continuing to issue such degrees without any change in the current situation is difficult for the examination department.”

Moreover, through a notification issued on March 25, 2019, the HEC had ordered around 24 universities to get their degrees, transcripts, postgraduate diplomas and provisional certificates printed from the National Security Printing Company.

The HEC’s order will be discussed in the next syndicate meeting. And it would be a shame if the practice of Urdu calligraphy on KU degrees is discontinued, because it’s part of the country’s literary heritage. “I’m also against computerised degrees because calligraphy makes KU’s degrees unique,” says Dr Hussain.

-

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene

Lana Del Rey Announces New Single Co-written With Husband Jeremy Dufrene -

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections

Ukraine-Russia Talks Heat Up As Zelenskyy Warns Of US Pressure Before Elections -

Lil Nas X Spotted Buying Used Refrigerator After Backlash Over Nude Public Meltdown

Lil Nas X Spotted Buying Used Refrigerator After Backlash Over Nude Public Meltdown -

Caleb McLaughlin Shares His Resume For This Major Role

Caleb McLaughlin Shares His Resume For This Major Role -

King Charles Carries With ‘dignity’ As Andrew Lets Down

King Charles Carries With ‘dignity’ As Andrew Lets Down -

Brooklyn Beckham Covers Up More Tattoos Linked To His Family Amid Rift

Brooklyn Beckham Covers Up More Tattoos Linked To His Family Amid Rift -

Shamed Andrew Agreed To ‘go Quietly’ If King Protects Daughters

Shamed Andrew Agreed To ‘go Quietly’ If King Protects Daughters -

Candace Cameron Bure Says She’s Supporting Lori Loughlin After Separation From Mossimo Giannulli

Candace Cameron Bure Says She’s Supporting Lori Loughlin After Separation From Mossimo Giannulli -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are ‘not Innocent’ In Epstein Drama

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Are ‘not Innocent’ In Epstein Drama -

Reese Witherspoon Goes 'boss' Mode On 'Legally Blonde' Prequel

Reese Witherspoon Goes 'boss' Mode On 'Legally Blonde' Prequel -

Chris Hemsworth And Elsa Pataky Open Up About Raising Their Three Children In Australia

Chris Hemsworth And Elsa Pataky Open Up About Raising Their Three Children In Australia -

Record Set Straight On King Charles’ Reason For Financially Supporting Andrew And Not Harry

Record Set Straight On King Charles’ Reason For Financially Supporting Andrew And Not Harry -

Michael Douglas Breaks Silence On Jack Nicholson's Constant Teasing

Michael Douglas Breaks Silence On Jack Nicholson's Constant Teasing -

How Prince Edward Was ‘bullied’ By Brother Andrew Mountbatten Windsor

How Prince Edward Was ‘bullied’ By Brother Andrew Mountbatten Windsor -

'Kryptonite' Singer Brad Arnold Loses Battle With Cancer

'Kryptonite' Singer Brad Arnold Loses Battle With Cancer -

Gabourey Sidibe Gets Candid About Balancing Motherhood And Career

Gabourey Sidibe Gets Candid About Balancing Motherhood And Career