In the peoples’ court

Legal eye

The writer is a lawyer based in

Islamabad.

There could be three possible instruments to remove Nawaz Sharif: the people, the court and the khakis. Ordinary folks in Pakistan, burdened by umpteen everyday challenges, weren’t outraged enough by the Panama leaks to instantly pour into the streets and demand Mr Sharif’s ouster.

Also gone is the era of the attention-hogging Iftikhar Chaudhry Supreme Court that would take suo motu cognizance of everything including a bottle or two of wine in a celebrity’s luggage. Imagine if Justice Chaudhry was the chief justice today. Imran Khan might have had to sing his praises again.

What we have today is a traditional SC: one that doesn’t envision itself as a maker of daily breaking news; one that sees its main function as being an arbiter in disputes between contesting parties, as opposed to becoming party to controversies itself. For such a cautious SC, the matter of the Panama leaks is as unpleasant a political thicket as can be. The leaks haven’t disclosed new scandals about the PM and his family. It has breathed life into old allegations. But to be legally actionable, the allegations will have to be backed by prosecutable evidence.

It is not the court’s function to find evidence. In common law adversarial systems such as ours judges rule on the basis of evidence and arguments presented by contesting parties. Their job is to remain focused on the material in the file before them and not be influenced by extraneous considerations such as claims of parties backed by their beliefs and not verifiable facts. Judges are bound by the principle that everyone is innocent until proven guilty. And in case of doubt the courts are required to grant its benefit to the accused.

In civil law based inquisitorial systems, judges and magistrates can be involved in investigating facts, and parts of the court are mandated to connect dots and dig out facts before determining whether there is enough evidence to take a matter to trial. As we know from Mr Zardari’s Swiss cases, it was a magistrate that had recommended that charges be prosecuted. The role of an investigator is partly partisan, for he can’t give the benefit of the doubt to an accused while probing the truth of allegations against him.

In our system a judge who exhibits any leaning in a case before him is deemed unfit to sit in judgement over it. Just because our ill-conceived Commission of Inquiry Act creates the option of appointing inquiry commissions comprising judges, to hope that inquiry judges, notwithstanding their training and judicial ethic of neutrality, will show spunk in digging out evidence in a matter as complex as the Panama leaks is foolhardy. And if they do find evidence and suggest prosecution, is there room for a trial where charges are framed by SC judges?

Inquiry commissions comprising judges can only serve the purpose of offering non-partisan policy advice in matters involving the law. The Saleem Shahzad Commission Report noted that while there wasn’t enough evidence to absolve intelligence agencies, there wasn’t enough evidence to find them guilty either. The CJ-led judicial commission investigating election-rigging complaints concluded that those alleging that elections were rigged had failed to discharge their onus of proof. Can one reasonably expect the Panama leaks commission to conclude anything different?

The Panama leaks scandal is hard to investigate. Within our nation-state system, it is the municipal laws of states that have teeth and not international law. Cross-jurisdictional investigations get stuck in a legal black hole. Without legal assistance treaties with offshore jurisdictions where funds might have been parked or assets purchased, who would volunteer the information that the commission would need? What means will the commission have to verify the declared value of the offshore companies (which own the London flats) purchased by the Sharifs?

It isn’t illegal for individuals to take money out of Pakistan through formal channels or to bring it back in. If the Sharifs haven’t been sloppy with basic math and documentation (ie their income and wealth declarations and the numbers and dates reflected in share-purchase agreements for their offshore companies) nothing will come out of the Panama commission, unless the commission TORs state that the Sharifs will be deemed guilty until they prove their innocence through evidence. It seems that the opposition has begun to realise this as well.

Other than the impossibility of the task before the Panama commission, it is also the timing of the deliverable that doesn’t help those who wish to dislodge NS in 2016. The Panama story is still unfolding. Another set of revelations is due on May 9. There might be more releases during the year. A commission comprising judges will issue notices to all who are named. These rich folks will then hire the best lawyers. With no incriminating materials magically flowing in from foreign jurisdictions and the challenge of converting ICIJ reports into admissible evidence in a formal trial, the circus could continue for years.

That brings us to the third instrument of removal: the khakis. Our military asserts tremendous influence from behind the curtain. But what ultimately backs such influence is the threat of direct intervention. For such threat to be acted upon you need a very ambitious chief or a government that is endangering the military’s institutional interests. We have neither situation today. The military’s domain and influence has swelled considerably in the last few years. How do you overthrow a government that either plays dead when you flex your muscle or joins the #ThankYouRaheelSharif chorus?

The army chief doesn’t come across as the coup-making sort. He has secured near-messiah status across the civil-military divide and would be disinclined to pursue any misadventures that could take the shine away from his name, reputation and legacy. While predictions can come back to haunt, it seems that he is all set to walk into the sunset in a few months. If NS can survive the summer of 2016 without provoking the khakis to strike, he will be home safe. Before the new chief finds his feet, it will all be about Election 2018.

So where does that leave the government and the opposition? The Zardari-led PPP has no compunctions about corruption and foreign assets – to put it mildly. What it can want from the Panama crisis is two things: to stay relevant and see if it can use this leash to revive itself in Punjab; or failing that, get something out of a cornered NS, such as immunity from control and intervention of federal agencies in Sindh. The PTI’s goals are different. The PTI’s best-case scenario is NS crumbling under pressure in 2016 and Imran Khan running a morality-accountability based campaign to claim Punjab in a mid-term election.

But if this wish can’t be granted yet again, the PTI would want to heat up the streets and continue drumming up the issue of Sharif’s corruption and immorality to expand its support base across Punjab. The Panama leaks are embarrassing for right-thinking supporters of the PML-N. If they can be kept confused and embarrassed enough till 2018 to be unwilling to come out and secure fortress Punjab for the Sharifs, the PTI will have succeeded in leveraging the Panama leaks appropriately. But then in the universe of politics 2018 is light years away.

NS seems to understand all this. He knows that to survive Panama, he doesn’t need to convert supporters of the PTI (or PPP) into believing that he is clean. He just needs to convince his own supporters that he isn’t dirty. But notwithstanding what his court jesters tell him, them eulogising him or a meaningless commission not finding him guilty won’t do the trick. He owes his supporters an explanation. And playing victim or alleging conspiracies isn’t enough. If he has nothing to hide, he must publicly disclose details of the Panama-routed London property transactions.

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

-

Scott Baio Reacts To Sudden Death Of 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Jennifer Runyon

Scott Baio Reacts To Sudden Death Of 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Jennifer Runyon -

Emilia, James Van Der Beek's Daughter, Shares How To Fight Grief After Losing A Loved One

Emilia, James Van Der Beek's Daughter, Shares How To Fight Grief After Losing A Loved One -

Rihanna Shooter: Police Reveal Identity Of Singer's Home Shooting Suspect

Rihanna Shooter: Police Reveal Identity Of Singer's Home Shooting Suspect -

Dolly Parton Ready To Marry Again?

Dolly Parton Ready To Marry Again? -

Savannah Guthrie Breaks Cover As Search For Mom Nancy Intensifies

Savannah Guthrie Breaks Cover As Search For Mom Nancy Intensifies -

Jennifer Lopez Shares Emotional Post After Discussing Split With Marc Anthony

Jennifer Lopez Shares Emotional Post After Discussing Split With Marc Anthony -

Andrew's Escape Plan Just Hit Unexpected Roadblock: 'Huge Blow'

Andrew's Escape Plan Just Hit Unexpected Roadblock: 'Huge Blow' -

Jessica Alba And Danny Ramirez Send Strong Message: Ignore Joe Burrow Rumours

Jessica Alba And Danny Ramirez Send Strong Message: Ignore Joe Burrow Rumours -

Dakota Johnson Leaves Fans Speechless With Calvin Klein Ad

Dakota Johnson Leaves Fans Speechless With Calvin Klein Ad -

Stephanie Faracy Talks About Her Role In 'Nobody Wants This' Season 3

Stephanie Faracy Talks About Her Role In 'Nobody Wants This' Season 3 -

Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Receive Fresh Warning

Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Receive Fresh Warning -

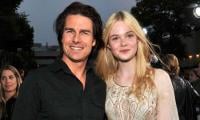

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards -

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer -

Paul Bettany Gets Honest About Voldemort Casting Rumours In 'Harry Potter' Series

Paul Bettany Gets Honest About Voldemort Casting Rumours In 'Harry Potter' Series -

Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner Show Support As Brody Jenner Reveals Big News

Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner Show Support As Brody Jenner Reveals Big News -

King Charles Plans Emotional Reunion With Lilibet, Archie

King Charles Plans Emotional Reunion With Lilibet, Archie