The giddy season

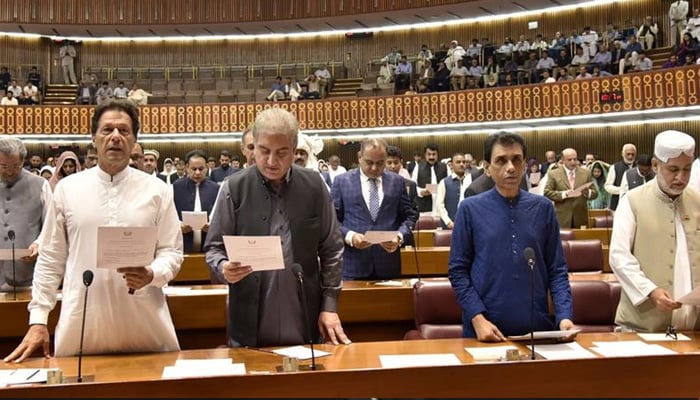

At the eve of Imran Khan being anointed prime minister, Pakistan is giddy with hope. Hope is a good thing – but when it begins to resemble silliness, one begins to worry. Drawing room conversations have become fantastic. The urban middle class surrounded by likeminded folk (which helps reinforce beliefs unimpeded by reason) is convinced that statecraft, like cricket, is a game of chance. With Kaptaan having become the captain of the ship, everything is now possible. All we need is one extraordinary spell and the game will be ours.

We are told that there has never been a time in Pakistan’s recent history that the country was as hopeful as it is now. The balance of payment crisis will sort itself out as we have a PM whom folks can trust and so expats will start sending money to Pakistan, something they previously didn’t do due to corrupt leaders. With a clean leader refusing to live in the PM’s mansion, simplicity and accountability will trickle down. With the Sharifs in jail and IK at the helm, the tremendous potential of this industrious nation is finally about to be unleashed, so we are told.

It’s too early in the day to expose bubbles to reason. But one worries about the longevity of happiness (especially of friends and family) relying on miracles. Remember Musharraf’s seven-point agenda (and its incidental similarity with the PTI’s 100-day plan): “rebuild national confidence; strengthen the federation; remove inter-provincial harmony; revive the economy and restore investor confidence; ensure law and order and dispense speedy justice; depoliticise state institutions; devolve power to [the] grassroots level; across-the-board accountability.”

Remember the hope there was post the lawyers’ movement? The law and the constitution had reigned supreme. We had told ourselves that, with the legitimacy of the law having overawed the brute power of a dictator, the fallen having risen against all odds and with the birth of an independent judiciary free from the establishment’s crutches, we were finally coming out of the woods and building a polity driven by rule of law. Those who were hopeful back then weren’t wrong either. But those bubbles burst eventually due to our failure to leap from populism to policy.

The economy won’t fix itself because expats previously lived in mortal fear of money sent to Pakistan being robbed by corrupt politicos and sent to offshore destinations. The property boom post-9/11 wasn’t caused due to faith in Musharraf’s honesty but due to fear of a backlash against Muslims in the West. Expats who could afford to buy property in Pakistan did so as an insurance policy. Expats will invest in Pakistan so long as the government can offer attractive schemes that guarantee a decent return on investment while keeping their capital safe.

Notwithstanding popular belief, money ‘stolen’ from Pakistan by our rulers and ‘stashed’ abroad isn’t sitting in an account or locker from where it can be brought back once our accountability system injects fear of God in the looters. Money changes form and hands. Money that has left Pakistan can’t be brought back even with the most valiant effort. What we need is not to bring back something that doesn’t exist as imagined, but to reverse reasons that produce flight of capital (and human resource) from Pakistan to more stable jurisdictions.

Return on investment is often higher in Pakistan than in jurisdictions where our money lands. But so is risk. Our real problem is state credibility. Its promises aren’t trustworthy. When it comes to property rights and solemnity of contracts, our state and legal system function like a lynch mob. Vested rights can be snatched without redress. Decades-old contracts can be undone. We’re disinterested in regulation but obsessed with price-fixing. You hear of an amnesty scheme one day and then about those availing it being hounded by state institutions.

Can we name one industrial group that is seen as having made its money the right way? So long as state policies are founded on the belief that all money is dirty and all moneyed folks legitimate NAB targets, we will not see an end to the flight of capital. And if such flight isn’t reversed and those with money don’t feel safe investing in Pakistan, how will job-creation come about? So if we wish to stem the flight of money and brains from Pakistan we will need to throw our weight behind sensible policies as opposed to populist whims and witch-hunts.

The PTI’s populism has paid dividends at the polls. It is now time to leap from populism to policy. And that is the big challenge for the PTI (and sensible folk like Asad Umar, Shafqat Mehmood etc within it). Announcements such as declining security or refusing to live in the PM House or bulldozing governors’ houses can whip up populist fervour but can’t move the needle for Pakistan. Symbolism is important and can set the tone for change. But that is all there is to it. Symbolism must be backed by thought-through policies to become the trigger for change.

The state can reassess how to manage the security of public office-holders more efficiently and cut out pomp and show. But with the kind of security threats alive in Pakistan, a PM without security protocol would be madness. There is little comment on the media over security protocol for service chiefs – and that is good. The last thing we need is losing a civilian or military leader to a terror attack. But we can do away with this tawdry business of counting security vehicles on TV to create time and energy for more substantive debates.

Likewise, the refusal of a PM to live in the PM’s official quarters in and of itself does nothing. But if it were part of a larger policy to reconsider the priorities of a state and to focus them on citizen welfare by rationalising state expenditure and allocation of resources and utilisation of state property, it would be another story. Let the government come up with a policy that taxpayers’ money won’t be utilised to subsidise the pompous lifestyle of public officials including state-run guesthouses, whether meant for use by politicos, generals, judges or babus.

Let the government come up with a policy that the perks of all public officials will be monetised, and that state land and resources tied up in providing official residences to politicos, generals, judges and babus will be freed up. Let the government announce that henceforth state-land (a fungible public resource to be held in trust for the citizens) will not be transformed into private property of public servants through plot and gallantry schemes. That state-land will only be employed for welfare schemes that benefit all citizens as a class and not a privileged subset.

Rule of law, for example, won’t persevere due to suo motus or a NAB chief taking note of Kiki challenges or the PTI initiating disciplinary proceedings against a violent MPA. To fix the justice system, we will need to fix each of its components: watch and ward, investigation, prosecution, courts and prisons. We will need to amend laws that create rent-seeking opportunities through litigation, penalise those seeking to delay adjudication of disputes, and inject efficiency and certainty into case and court management systems by taking out the arbitrariness that pervades all across.

As long as IK’s populist announcements are symbols marking the behavioural change that will be affected by well-thought-through policies, it’s okay. But the bottom line is that gimmickry can be a marketing feature of a policy but not the policy itself. We are a big country with complex problems. One can sell all sorts of fantasies to the gullible voter prior to an election, but delivering on promises to bring fantasies to life requires hard-nosed and pain-inducing institutional and structural reform.

We have been lagging behind, but not just because Sharifs or Zardaris happened to us. We are lagging behind because our worldview is blinkered and conspiratorial, our priorities myopic and retrogressive, our state’s view of security trumps citizen welfare, our civil-military imbalance is a constant source of infighting, and our institutions are inefficient and prone to whimsical tantrums. Let’s hope IK is up to the monumental challenge before him. Statecraft, after all, is no game of chance.

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad.

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

-

Hong Kong Court Sentences Media Tycoon Jimmy Lai To 20-years: Full List Of Charges Explained

Hong Kong Court Sentences Media Tycoon Jimmy Lai To 20-years: Full List Of Charges Explained -

Coffee Reduces Cancer Risk, Research Suggests

Coffee Reduces Cancer Risk, Research Suggests -

Katie Price Defends Marriage To Lee Andrews After Receiving Multiple Warnings

Katie Price Defends Marriage To Lee Andrews After Receiving Multiple Warnings -

Seahawks Super Bowl Victory Parade 2026: Schedule, Route & Seattle Celebration Plans

Seahawks Super Bowl Victory Parade 2026: Schedule, Route & Seattle Celebration Plans -

Keto Diet Emerges As Key To Alzheimer's Cure

Keto Diet Emerges As Key To Alzheimer's Cure -

Chris Brown Reacts To Bad Bunny's Super Bowl LX Halftime Performance

Chris Brown Reacts To Bad Bunny's Super Bowl LX Halftime Performance -

Trump Passes Verdict On Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show

Trump Passes Verdict On Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show -

Super Bowl 2026 Live: Seahawks Defeat Patriots 29-13 To Win Super Bowl LX

Super Bowl 2026 Live: Seahawks Defeat Patriots 29-13 To Win Super Bowl LX -

Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton Make First Public Appearance As A Couple At Super Bowl 2026

Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton Make First Public Appearance As A Couple At Super Bowl 2026 -

Romeo And Cruz Beckham Subtly Roast Brooklyn With New Family Tattoos

Romeo And Cruz Beckham Subtly Roast Brooklyn With New Family Tattoos -

Meghan Markle Called Out For Unturthful Comment About Queen Curtsy

Meghan Markle Called Out For Unturthful Comment About Queen Curtsy -

Bad Bunny Headlines Super Bowl With Hits, Dancers And Celebrity Guests

Bad Bunny Headlines Super Bowl With Hits, Dancers And Celebrity Guests -

Insiders Weigh In On Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton's Relationship

Insiders Weigh In On Kim Kardashian And Lewis Hamilton's Relationship -

Prince William, Kate Middleton Private Time At Posh French Location Laid Bare

Prince William, Kate Middleton Private Time At Posh French Location Laid Bare -

Stefon Diggs Family Explained: How Many Children The Patriots Star Has And With Whom

Stefon Diggs Family Explained: How Many Children The Patriots Star Has And With Whom -

‘Narcissist’ Andrew Still Feels ‘invincible’ After Exile

‘Narcissist’ Andrew Still Feels ‘invincible’ After Exile