Pakistan’s value addition gap: why cheap labour alone won’t deliver

LAHORE: Pakistan produces low value-added goods not just because of low wages, but due to structural gaps in strategy, investment and value-chain integration. Vietnam’s example shows that value addition stems from policy vision, infrastructure, training and trade connectivity.

All countries that excel in value addition have made concerted efforts to aggressively integrate with global markets. Part of the reason Pakistan continues to export low value-added products is economic displacement: many developed -- and now even some developing -- economies have moved away from such products for various reasons. Rising labour costs have made low-margin, labour-intensive goods unfeasible. These countries have shifted their focus to innovation, high-tech manufacturing, and services.

Pakistan’s comparative advantage in cheap labour (relative to developed nations and China) makes it more feasible to produce low-end goods. However, cheap labour alone does not ensure competitiveness or sustainability, as seen in the case of Vietnam. Vietnam demonstrates that low wages are not the sole factor for success. Despite wages there being higher than in Bangladesh and close to or above India’s, it has still outcompeted many.

The proactive policies of the Vietnamese government attracted FDI, particularly from South Korea, Japan and China. Vietnam secured better trade agreements such as the EU-Vietnam FTA, CPTPP and RCEP. Another advantage is its robust infrastructure, superior to Pakistan’s and often India’s. Vietnam has integrated into the global economy by improving its ease of doing business and establishing special economic zones. These measures have helped it embed itself in global value chains, especially in electronics and high-end apparel.

Beyond textiles, Pakistan exports other products too. It holds a niche in surgical instruments, but this is mostly low- to mid-value-added (OEM manufacturing). Similarly, its footwear and leather goods exports are largely in the low-end category (semi-processed leather rather than branded fashion products). Software and IT services have only recently started to flourish, with some mid-tier offerings, but nothing comparable in scale or quality to India’s exports. Pakistan’s electronics exports remain extremely limited and are not high-tech -- typically at the assembly level. Most of these exports are still low to medium value-added, with minimal brand ownership or design.

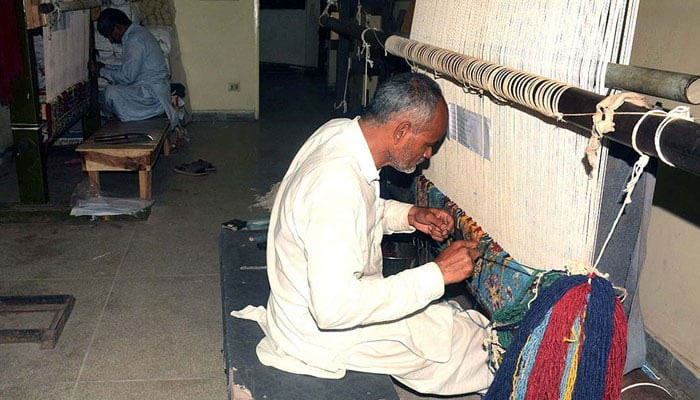

There is scope to add higher value to Pakistan’s textile and other exports. In textiles, a significant share of exports still comprises yarn and greige fabric, which are low value-added. Apparel exports remain undiversified and focused on basic items (eg, T-shirts, towels, socks). Competing countries have moved into fashion garments, sportswear, technical textiles, and branded products.

To upgrade its textiles, Pakistan needs stronger design and branding capabilities, much like Bangladesh, which collaborates with Western buyers and increasingly with local designers. Entrepreneurs must invest in fashion technology, R&D and synthetic fibres. The industry also needs to improve compliance and sustainability standards to access premium markets. These steps will help textile firms integrate with global retail and fast fashion chains.

There is a dire need to upskill the textile workforce beyond just cheap labour. The sector must produce technicians, pattern makers, and merchandisers -- roles that command significantly higher wages than the industry typically pays its textile labour force. Even in Bangladesh, high-end skills fetch far better wages.

Several reasons explain why value addition has lagged in Pakistan. The fundamental issue is the absence of a long-term industrial policy. Energy and logistics bottlenecks have disrupted business planning. Poor coordination between industry, academia, and government has also stifled innovation. Limited FDI inflows -- often a result of regulatory unpredictability and security concerns -- have resulted in negligible investment in technology upgrades and design development. The race to the bottom in wages alone will never deliver if other critical enablers of growth are missing.

-

Savannah Guthrie Shares Sweet Childhood Video With Missing Mom Nancy: Watch

Savannah Guthrie Shares Sweet Childhood Video With Missing Mom Nancy: Watch -

Over $1.5 Million Raised To Support Van Der Beek's Family

Over $1.5 Million Raised To Support Van Der Beek's Family -

Diana Once Used Salad Dressing As A Weapon Against Charles: Inside Their Fight From A Staffers Eyes

Diana Once Used Salad Dressing As A Weapon Against Charles: Inside Their Fight From A Staffers Eyes -

Paul Anthony Kelly Opens Up On 'nervousness' Of Playing JFK Jr.

Paul Anthony Kelly Opens Up On 'nervousness' Of Playing JFK Jr. -

Video Of Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise 'fighting' Over Epstein Shocks Hollywood Fans

Video Of Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise 'fighting' Over Epstein Shocks Hollywood Fans -

Jelly Roll's Wife Bunnie Xo Talks About His Huge Weight Loss

Jelly Roll's Wife Bunnie Xo Talks About His Huge Weight Loss -

Margot Robbie Reveals Why She Clicked So Fast With Jacob Elordi

Margot Robbie Reveals Why She Clicked So Fast With Jacob Elordi -

Piers Morgan Praised By Ukrainian President Over 'principled Stance' On Winter Olympics Controversy

Piers Morgan Praised By Ukrainian President Over 'principled Stance' On Winter Olympics Controversy -

Halsey's Fiance Avan Jogia Shares Rare Update On Wedding Planning

Halsey's Fiance Avan Jogia Shares Rare Update On Wedding Planning -

Instagram Head Adam Mosseri Says Users Cannot Be Clinically Addicted To App

Instagram Head Adam Mosseri Says Users Cannot Be Clinically Addicted To App -

James Van Der Beek Was Working On THIS Secret Project Before Death

James Van Der Beek Was Working On THIS Secret Project Before Death -

Las Vegas Father Shoots Daughter's Boyfriend, Then Calls Police Himself

Las Vegas Father Shoots Daughter's Boyfriend, Then Calls Police Himself -

'Hunger Games' Star Jena Malone Shocks Fans With Huge Announcement

'Hunger Games' Star Jena Malone Shocks Fans With Huge Announcement -

Ex-OpenAI Researcher Quits Over ChatGPT Ads

Ex-OpenAI Researcher Quits Over ChatGPT Ads -

Prince William Criticized Over Indirect Epstein Connection

Prince William Criticized Over Indirect Epstein Connection -

'Finding Her Edge' Creator Explains Likeness Between Show And Jane Austin Novel

'Finding Her Edge' Creator Explains Likeness Between Show And Jane Austin Novel