Parachuted manifestos

I reviewed manifestos of three major parties – PML-N, PPP, and PTI – that have held power at some points in past

The election manifestos of all major parties have now been released. I went through them with an eye on education priorities. If education is an election issue for you that will determine in whose favour you will cast your vote, keep reading.

I reviewed the manifestos of the three major parties – the PML-N, PPP, and PTI – that have held power at some points in the past. I also included the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) as the fourth major party and two budding progressive parties – the Awami Workers Party (AWP) and the Haqooq-e-Khalq Party (HKP), because every dog has its day. You never know when someone in a smoke-filled room decides it is time to let someone new have a go at it. The AWP and HKP’s education plans are progressive but sparse and a number of items impractical and uninformed.

The key takeaway from all manifestos is this: The promises parties make to secure votes are not the promises that will address problems of the school and university sectors.

In that sense, the education manifestos of the four big parties – PML-N, PPP, PTI, and JI – are what I would like to describe as parachute manifestos: disconnected from the ground realities and ignorant of all public debates of recent years. The issues in the education sector that emerged in the last few years are left unaddressed. A lot of deep-seated problems require changes to existing laws and/or policies or writing new ones. This means they can be addressed in full or in part without spending public funds.

For example, when you speak to faculty members in universities, there seems to be only one issue on anyone’s mind: the two different service tracks permanent faculty members in universities are appointed on – the traditional Basic Pay Scale and the relatively new Tenure Track System (TTS). Put simply, each wants a service benefit that only the other track offers, leading to unhappiness all around.

If you speak to university leaders, one of their biggest problems is the discontinuation of the sizable financial contribution by the HEC to the salaries of university faculty appointed on TTS. Another one is the infringement on university autonomy by education departments, bureaucracy in general, and various political offices. Governance issues, all. But none of the manifestos of these big four parties are offering anything in the way of governance reforms.

Broadly speaking, the manifestos read like laundry lists of spending programmes, goodies, and giveaways. The lists are long, expensive, and mostly unrealistic. No one in any party bothered to sit down and work out the costs of the programmes being promised. Serious parties issuing serious manifestos in serious democracies work out at least two things when they put forward a serious programme proposal: a) A cost estimate and b) where that money will come from.

Both are missing for every programme in the manifestos of all parties (education spending promises as a percentage of GDP excluded). For this reason, I cannot take them seriously even as mere intentions. On this point I would like to make a special mention of the PML-N here which has been touting its election promises as “realistic”, but I cannot see how.

The PML-N’s manifesto presents a (largely) progressive wish list of nuts-and-bolts programmes – for example, a school lunch programme, double shifts in schools, universal early childhood and school education, expansion of scholarship programmes, etc – all things I wish for all school students, but expensive and unlikely to grow beyond pilot-scale. It is also the longest of all education manifestos, looks incredibly expensive, and, therefore, ultimately unrealistic.

The PML-N’s agenda for higher education is more conventional: Promises of more universities, more public funding, establishing endowment funds, etc. An item that caught my eye: a promise to put a medical and engineering college in every district. As expensive as it is, opening a new higher education institution in name only is not the problem. I am sure private sector players would be more than happy to step in and oblige if they are guaranteed charters. There is a crisis of quality of education in most universities (and schools, for that matter), a reality that is not acknowledged by manifestos.

The PPP’s education manifesto can be described in one word as ‘basic’. It does not list any priorities that one could disagree with, e.g., universal access to school education and all the material resources that entails, gender parity, inclusivity, vocational training, teacher training, teaching in local languages etc. The PPP has been running Sindh non-stop since 2008 which has been its stronghold for decades. These promises would be more convincing if one could see at least some of them enacted and improving the state of education in its own backyard. However, of the four major parties, the PPP is the only one that explicitly expresses its support for strengthening provinces’ role in education. Both the PTI and JI explicitly favour greater centralization while the PML-N’s manifesto is rather quiet on this issue.

The PTI’s Charter of Education suggests it has learned a few lessons from its ham-handed attempts at education reform. Notably, there is no longer any mention of the Single National Curriculum, but remnants of it are still visible. It still includes making “interesting textbooks” and “revamping” the examination system. Never mind that it claims to have both these things in its last tenure. It has stepped back from its talk of enforcing a single school system, a promise that has been picked up by the JI and AWP in this election cycle. Very importantly, the inclusion of “strengthening central institutions” signals its continued keenness to reverse the devolution of education under the 18th Amendment to the constitution.

On higher education, it promises to do the opposite of what it delivered in its last term – an increase in funding, a promise you can find in every party’s manifesto. It promises to “guarantee curriculum relevance”, “regular curriculum updates” and “ensure curricula are in sync with… needs of industries.” These are jobs for universities, not politicians or political parties. It appears reminiscent of the SNC.

The JI’s education manifesto endeavours for a single school system, like the PTI once did. It seeks to reverse the devolution of education to provinces by a constitutional amendment. It also promises to make Urdu the medium of instruction, ignoring the fact that in many parts of the country, it is not children’s mother tongue, which is like teaching primary schoolers in a foreign language. Furthermore, it promises price controls on private schools, which can only drive private schools out of the education sector, further compounding the crisis of access to schools. Its list of goodies and giveaways is slightly shorter - houses for all teachers and scholarships for students. Of course, the JI being the JI, is promising lots and lots more Islamization of education.

The Urdu version of the manifesto includes some more Taliban-esque agenda items that are omitted from the English versions posted on social media platforms, the most ominous of which is segregating universities. Given that it took us 75-odd years to get to 250 universities today, one wonders how long the JI would take to enact this one agenda item. I am assuming that just like in Afghanistan, women would be sent home and deprived of a higher education until the JI can be bothered to build new women-only universities. Its vision for the country and the education sector is by far the most regressive of all parties.

The JI’s education manifesto is terrifying. If there is a cosmic thumb capable of tilting the electoral scales for or against a party, one hopes it always exerts its force against the JI. The thought of seeing our country follow in the footsteps of Afghanistan is too terrible to contemplate. One has to give them credit for making no bones about what they want to see done.

In the last few years, the school education issues that rose to prominence in public debates included abandoned attempts to introduce a single school system, federally dictated school textbooks (both of which reduced choices for private schools), continued poor quality of education, attempts to reverse devolution of education, vilification of the private schools that serve roughly half of school-going children, and the widespread destruction of schools by floods.

In the higher education sector, the issues that came up were multiple service structures for faculty, careless approval of university charters, the fact that almost all public universities are incapable of sustaining themselves, have not developed sizable endowments but depend on public funds to stay open, and, finally, the poor quality of education imparted by most university programs.

Not one party manifesto acknowledges these issues or is willing to address them directly.

The writer (she/her) has a PhD in Education.

-

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame -

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus -

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’ -

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter -

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud -

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels -

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing -

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras -

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards -

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest -

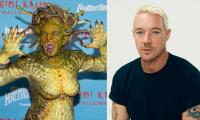

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween'

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween' -

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down -

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest?

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest? -

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights -

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed