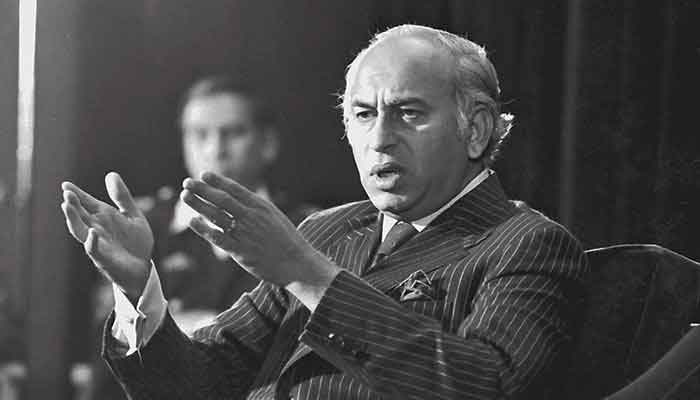

Remembering Bhutto the writer-Part I

A lot has been written about his rise and fall, about his achievements and failures, and about his decisions – right and wrong – that led him to the gallows.

Today marks the 40th death anniversary of Z A Bhutto, arguably the most intelligent and well-read political leader Pakistan has had in its 72-year history.

A lot has been written about his rise and fall, about his achievements and failures, and about his decisions – right and wrong – that led him to the gallows.

Here we discuss him as an active politician who not only participated in some of the salient events of our history but also documented his observations and wrote with a felicity not many leaders have possessed in Pakistan.

Those who knew Bhutto, both friends and foes, testify that he was a genius who enraged some mediocre people who had aspired for higher positions, and their mediocrity – coupled with at times unwarranted arrogance by ZAB himself – led ultimately to his downfall. That Molvi Mushtaq, Anwarul Haq, Ziaul Haq and some of ZAB’s close associates were mediocre is not a secret. The first three were especially clearly smitten by ZAB’s far superior capacity to work wonders with the people. These three held grudges against ZAB and when the time came, they struck with unabashed ruthlessness and vengeance.

Here we are more concerned with his writings and how he found time – like all great leaders do – to read at a tremendous pace, and then write with a prolific pen. Students of the history of Pakistan cannot and should not ignore what Bhutto wrote. Though he gave his own version, rather than trying to be an objective historian, his insights help us understand the turns and twists of the 1960s and 1970s. His book, ‘The Myth of Independence’ (1969) is a chronicle of his entry to and exit from the various ministries that fell into his lap, sometimes unexpectedly.

For example, his appointment as the foreign minister of Pakistan in 1963 was the result of the sudden departure of Muhammad Ali Bogra, Pakistan’s foreign minister for seven months, who died in Dhaka at the age of just 53. Who would have known that ZAB’s life would also be cut short in 1979 just at the age of 51? ZAB’s ‘The Myth of Independence’ is a rich source of history; in less than 200 pages, he summarises all major events spanning over a decade during his early engagements with foreign affairs and how he saw and tackled some of the most challenging tasks given to him by General Ayub Khan.

But his much more informative book is even shorter, comprising hardly 100 pages including the text of the Six-Point Formula with both the original and the amended points; the salient extracts from the legal Framework Order (LFO – 1970); and the text of the broadcast to the nation by General Yahya Khan on March 26, 1971. ‘The Great Tragedy’, written during the tumultuous months of 1971, is a compact treasure trove for anyone interested in knowing how the events unfolded in quick succession and how ZAB himself played an active role as one of the major interlocutors in almost all political discussions at the highest level.

One wonders how he was able to put his pen to paper when a bitter civil war was going on in the country, one in which ZAB was not a silent spectator. He was very much part of the disintegration process in Pakistan. ‘The Great Tragedy ‘starts with the events of 1971 and goes back to the LFO and the assumption of power by General Yahya Khan in 1969. Then it discusses the events prior to the removal of General Ayub Khan and covers the Agartala Conspiracy Case and the background to the Six Points presented by Sheikh Mujibur Rehman in 1966.

But for readers’ convenience, we begin where the book ends. On the last page of ‘The Great Tragedy’, Z A Bhutto writes:

“The people did not fight and sacrifice for the creation of Pakistan so that they might be ruled indefinitely by a Generals’ Junta, ruthlessly exploited by a handful of capitalists, bullied by bureaucrats, and lashed into obedience on the orders of mobile military courts. Nor have the poor people of Pakistan toiled for years to see their Pakistan come to this pass. The people demand the Pakistan for which they have fought, sacrificed and toiled, in which they are their own masters, free from all forms of exploitation, and in which their children can be properly housed, fed, clothed, and educated.”

In this one paragraph, he has summarised the aspirations of the people of Pakistan; the aspirations that almost half a century later remain unfulfilled and unrealized. That he was not given time to achieve what he wanted, remains a great tragedy in itself. The people are still bullied, exploited, and lashed into obedience, and the severity of these undeserved punishments keeps intensifying. Forty years after Bhutto’s unceremonious exit and unconvincing execution, the people are not only bullied, they are also butchered on campuses and in classrooms; they are not only lashed into obedience, but also lifted into oblivion.

On page 87, ZAB writes: “Despite the fact that Pakistan was created by the free will of Muslims of the Subcontinent, there are many foreign observers who still persist in saying that Pakistan is an artificial state. One may well ask: what is a natural state and an artificial state? If Pakistan is an artificial state, how can Czechoslovakia, or Yugoslavia, for instance be considered as natural states?” Little did Bhutto know that both Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia would disintegrate within decades after his death. He continued to apply the same logic on the erstwhile USSR.

“To what extent is the Soviet Union a natural state? How did it acquire its present shape? What are the common denominations between the Republic of Russia and the Republics of Central Asia? Where do their natural links lie?” Again, not only did the USSR fall apart, but ZAB’s own country that he was trying to preserve while fighting against the Six Points of Mujibur Rehman too disintegrated within months after he wrote ‘The Great Tragedy’ in the summer of 1971. Be it Czechoslovakia or Pakistan, the USSR or Yugoslavia, countries fall apart for two main reasons.

One, if the establishment refuses to grant democratic rights to the people; and two, if the autonomy of smaller administrative units is usurped. In 1971, East Pakistan fought for separation not because Bhutto refused to negotiate. Pakistan disintegrated because General Yahya Khan refused to hand over power to the elected representatives of the people who had won the elections in the eastern and western wings of Pakistan. Blaming Bhutto for East Pakistan’s secession is like accusing him of triggering the war in 1965, or blaming Benazir Bhutto for the Taliban atrocities in Afghanistan or finding faults with Nawaz Sharif for the Kargil fiasco.

Despite all his intelligence, Bhutto was not free from rhetoric. For example, read this: “In a sense, the starting point of Pakistan goes over a thousand years to when Mohammad bin Qasim set foot on the soil of Sind (sic) and introduced Islam in the Subcontinent. The study of the Mogul and British periods will show that the seeds of Pakistan took root in the sub-continent from the time Muslims consolidated their position in India.”

Tracing the roots of Pakistan to Allama Iqbal or to Sir Syed Ahmad Khan may have some truth in it. But locating it in the 8th century is a stretch, propounded by the historians such as I H Qureshi. To conclude the first part of this series, let’s read this from ZAB and see how relevant he is even today: “We have inherited a terrible legacy of unforgiveable mistakes: we have become answerable for the sins of the Old Guard. Superficial minds without an elementary knowledge of politics, without any sense of history, have made fundamental political decisions which have brought Pakistan perilously close to ruin.”

To be continued

The writer holds a PhD from the: University of Birmingham, UK and works in Islamabad.

Email: mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk

-

King Charles ‘very Much’ Wants Andrew To Testify At US Congress

King Charles ‘very Much’ Wants Andrew To Testify At US Congress -

Rosie O’Donnell Secretly Returned To US To Test Safety

Rosie O’Donnell Secretly Returned To US To Test Safety -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Spotted On Date Night On Valentine’s Day

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Spotted On Date Night On Valentine’s Day -

King Charles Butler Spills Valentine’s Day Dinner Blunders

King Charles Butler Spills Valentine’s Day Dinner Blunders -

Brooklyn Beckham Hits Back At Gordon Ramsay With Subtle Move Over Remark On His Personal Life

Brooklyn Beckham Hits Back At Gordon Ramsay With Subtle Move Over Remark On His Personal Life -

Meghan Markle Showcases Princess Lilibet Face On Valentine’s Day

Meghan Markle Showcases Princess Lilibet Face On Valentine’s Day -

Harry Styles Opens Up About Isolation After One Direction Split

Harry Styles Opens Up About Isolation After One Direction Split -

Shamed Andrew Was ‘face To Face’ With Epstein Files, Mocked For Lying

Shamed Andrew Was ‘face To Face’ With Epstein Files, Mocked For Lying -

Kanye West Projected To Explode Music Charts With 'Bully' After He Apologized Over Antisemitism

Kanye West Projected To Explode Music Charts With 'Bully' After He Apologized Over Antisemitism -

Leighton Meester Reflects On How Valentine’s Day Feels Like Now

Leighton Meester Reflects On How Valentine’s Day Feels Like Now -

Sarah Ferguson ‘won’t Let Go Without A Fight’ After Royal Exile

Sarah Ferguson ‘won’t Let Go Without A Fight’ After Royal Exile -

Adam Sandler Makes Brutal Confession: 'I Do Not Love Comedy First'

Adam Sandler Makes Brutal Confession: 'I Do Not Love Comedy First' -

'Harry Potter' Star Rupert Grint Shares Where He Stands Politically

'Harry Potter' Star Rupert Grint Shares Where He Stands Politically -

Drama Outside Nancy Guthrie's Home Unfolds Described As 'circus'

Drama Outside Nancy Guthrie's Home Unfolds Described As 'circus' -

Marco Rubio Sends Message Of Unity To Europe

Marco Rubio Sends Message Of Unity To Europe -

Savannah's Interview With Epstein Victim, Who Sued UK's Andrew, Surfaces Amid Guthrie Abduction

Savannah's Interview With Epstein Victim, Who Sued UK's Andrew, Surfaces Amid Guthrie Abduction