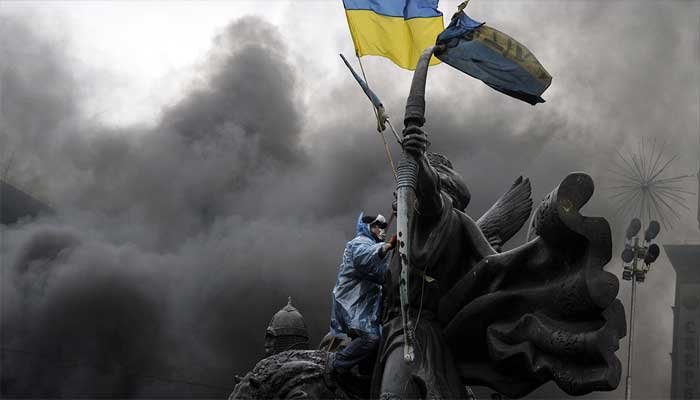

Ukraine crisis: Afghan spillover leveraged in Kazakhstan’s hybrid war

A destabilising geopolitical pattern is emerging as Central Asia and Afghanistan's neighbourhood is entangled in a new wave of proxy battle. The main players are America and Russia. While the Ukraine crisis was reverberating in Kazakhstan, the US successfully leveraged the Afghanistan spillover as the main driver of instability, as per Central Asian watchers.

West Asia politics stirred when Turkmenistan, Iran, Pakistan and Chinese border skirmishes involved a proxy group of local Taliban fighters. To make sense of what the region went through, we need to understand the context of the Ukrainian crisis. The Russian strategic aim behind its massive deployment on the borders of Ukraine was a regime change in Kyiv and subsequent annexation of the country. This plan leaked and the US mustered its counter moves and selected the theatre of Central Asia and Afghanistan, employing the dynamic of hybrid war.

There are five countries around Afghanistan that Washington has in varying degrees deteriorated its bilateral relations, i.e, China, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Russia–as resident power in Central Asia. The US has deep experience in regime change in Central Asia in the past using NGOs to support proxy groups and back their kinetic actions.

This time Tajikistan was chosen and its anti-government forces were targeted. The proxy forces were mainly drawn from secular and extremist militants comprising a mix of Turkestani militants–who were under the protection of the Taliban–and the pro-Taliban group relocated to the border region. The secular anti-Moscow backed government raised forces was the opposite camp, with clandestine help from the far away deep state of India – a strategic US partner.

The main objective of possible implosion of Tajikistan would serve another purpose: Its security is intertwined with Afghanistan and by extension with the stability of Afghanistan's neighbours. Some proxy Afghan Taliban groups were additionally used against Iran, Pakistan and Turkmenistan by engaging in border skirmishes, provoking actions and removing fences on the Pakistani border respectively. The same will probably be repeated with China as anti-Chinese militants are drafted and deployed along the Afghan border extending to Beijing. China is likely to publicly react to such events which are about to unfold on its border with deep anxiety for its security in Xinjiang province.

Furthermore, these proxy kinetic moves, however, sent shock waves across Moscow, Tehran, Islamabad, and now Beijing fearing that another theatre was unfolding right on their doorsteps.

To off-balance Moscow in Eastern Europe, for behavioural reversal in Ukraine in particular, one added distraction–larger in scale though–was created for Russia in Kazakhstan. The usual suspect was NED (National Endowment for Democracy) and it’s funding for the proxies that went kinetic, leveraging inflation and local issues. The money trail is established as many Central Asia watchers believe that the NED is a front for the CIA though the US has never acknowledged so did the CIA due to blowback risk. And millions of dollars were invested in groups with a hostile agenda.

Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev said militants from Afghanistan and the Middle East were used as proxies in this crisis. While the template was successfully experienced in Ukraine in 2014, it was being repeated in Kazakhstan. The NED has also sponsored PR campaigns and anti-govt bodies in Pakistan investing around $4.5 million in 2020 alone.

This latest mayhem in Central Asia distracted Russia from Ukraine and delayed the annexation plan till Moscow stabilised its sphere of influence. However, whether it would have deterrent value in Ukraine is not clear yet.

Still a far crisis in Eastern Europe has found strong traction in Central and West Asia as the main theatre implicating Russia, to a lesser extent Turkmenistan, Iran, Pakistan, and now China.

This brings us back to the US hybrid strategy (meant for deterrence and behavioural change of the countries): The group (s) drafted in ranks of Afghan Taliban have irked the regional countries backing the Taliban, to the glee of Washington. Now going forward, the Afghan Taliban will be viewed with deep suspicion from Moscow, Beijing to Islamabad and Tehran as they have so far refused to neutralise the potential and actual proxy groups focused on Afghanistan's neighbours.

The stakes for the region are high and so is for Pakistan. Here is what Pakistan can do to stabilise Afghanistan and calm nerves in the region in a bid to ameliorate the challenging situation. Islamabad has no substantive leverage on the Taliban. However, it can be enhanced by taking these three steps, i.e, a: nearly recognize the Taliban as a legitimate government of Afghanistan; b: send out doctors and engineers to take over collapsed hospitals left by Western NGOs; c: train Taliban's intelligence outfit drawing from regime's disbanded NDS members.

The above strategy will provide the Afghan Taliban enough incentive to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a hotbed of a new round of insurgency and deny sanctuary for militants focused on neighbouring countries' stability. Of course, this is some type of pushback as far as Pakistan is concerned.

Meanwhile, paranoid Moscow and the region will connect the dots when they witness US overt support for NGOs and would assume covert help for toppling govts and destabilising other countries perceived to be hostile or less friendly towards the US.

This is why Moscow has shown stronger resolve in recent talks with the US on the Ukraine crisis. Given the zero blowback of overt use of proxy NGOs as a front and through them kinetic operations, the US is well-poised to put in place some deterrent value for reversals on certain issues such as Russian pullback from Ukraine, halting Chinese BRI and CPEC in its tracks and Iran's belligerence.

In a nutshell, this is a boundaryless geopolitical contest involving, in large part, the interstate rivalry between China and US, Russia and US, Pakistan and US, Iran and US manifested in proxy warfare in gray zones and nonviable states and regions of Central Asia and West Asia. A pushback in varying degrees from all these countries is imminent – welcome to a new version of the Cold War.

Jan Achakzai is a geopolitical analyst, a politician from Balochistan and an ex-adviser to the Balochistan Government on media and strategic communication. He remained associated with BBC World Service. He is also Chairman of the Institute of New Horizons (INH) & Balochistan. He tweets @Jan_Achakzai

-

Prince William, Kate Middleton Camp Reacts To Meghan's Friend Remarks On Harry 'secret Olive Branch'

Prince William, Kate Middleton Camp Reacts To Meghan's Friend Remarks On Harry 'secret Olive Branch' -

Daniel Radcliffe Opens Up About 'The Wizard Of Oz' Offer

Daniel Radcliffe Opens Up About 'The Wizard Of Oz' Offer -

Channing Tatum Reacts To UK's Action Against Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor

Channing Tatum Reacts To UK's Action Against Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor -

Brooke Candy Announces Divorce From Kyle England After Seven Years Of Marriage

Brooke Candy Announces Divorce From Kyle England After Seven Years Of Marriage -

Piers Morgan Makes Meaningful Plea To King Charles After Andrew Arrest

Piers Morgan Makes Meaningful Plea To King Charles After Andrew Arrest -

Sir Elton John Details Struggle With Loss Of Vision: 'I Can't See'

Sir Elton John Details Struggle With Loss Of Vision: 'I Can't See' -

Epstein Estate To Pay $35M To Victims In Major Class Action Settlement

Epstein Estate To Pay $35M To Victims In Major Class Action Settlement -

Virginia Giuffre’s Brother Speaks Directly To King Charles In An Emotional Message About Andrew

Virginia Giuffre’s Brother Speaks Directly To King Charles In An Emotional Message About Andrew -

Reddit Tests AI-powered Shopping Results In Search

Reddit Tests AI-powered Shopping Results In Search -

Winter Olympics 2026: Everything To Know About The USA Vs Slovakia Men’s Hockey Game Today

Winter Olympics 2026: Everything To Know About The USA Vs Slovakia Men’s Hockey Game Today -

'Euphoria' Star Eric Made Deliberate Decision To Go Public With His ALS Diagnosis: 'Life Isn't About Me Anymore'

'Euphoria' Star Eric Made Deliberate Decision To Go Public With His ALS Diagnosis: 'Life Isn't About Me Anymore' -

Toy Story 5 Trailer Out: Woody And Buzz Faces Digital Age

Toy Story 5 Trailer Out: Woody And Buzz Faces Digital Age -

Andrew’s Predicament Grows As Royal Lodge Lands In The Middle Of The Epstein Investigation

Andrew’s Predicament Grows As Royal Lodge Lands In The Middle Of The Epstein Investigation -

Rebecca Gayheart Unveils What Actually Happened When Ex-husband Eric Dane Called Her To Reveal His ALS Diagnosis

Rebecca Gayheart Unveils What Actually Happened When Ex-husband Eric Dane Called Her To Reveal His ALS Diagnosis -

What We Know About Chris Cornell's Final Hours

What We Know About Chris Cornell's Final Hours -

Scientists Uncover Surprising Link Between 2.7 Million-year-old Climate Tipping Point & Human Evolution

Scientists Uncover Surprising Link Between 2.7 Million-year-old Climate Tipping Point & Human Evolution