Deferring poverty alleviation?

Absolute poverty is a state of severe deprivation and denial of basic human rights. Hunger and dispossession affect the entire life cycle, keeping people away from actively and meaningfully participating in the social, economic and political sphere of life and bringing immense suffering, pain and psychological effects.

Therefore, poverty alleviation must be the first and foremost development policy goal of any democratic government, with clear time-bound targets and milestones to measure and report progress.

Unfortunately, poverty alleviation has not attained the level of political priority in Pakistan given its importance and urgency. Whether media or legislative discussions, one will hardly find dedicated discourse to make it a part of essential political debate – except some nice but unattainable documents in dusty official racks.

There have been two major global commitments – the Millennium Development Goals implemented from 2000 to 2015 and now the Sustainable Development Goals from 2016 to 2030. Poverty alleviation has been the very first goal in both frameworks.

In contrast, the debate in Pakistan has always focused on fabricating and fudging figures to show a reduced number of poor people for political gains rather than a real decrease in the actual number of poor people. For a long time after adopting the MDGs, the debate remained around determining the national poverty line and measuring it. Later, the World Bank revised the global poverty line to $1.90. Simultaneously, the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative started measuring multidimensional poverty – departing from traditional measures based on food calorie intake. MPI included fifteen indicators of three broader dimensions of schooling, health and standard of living to measure wellbeing.

The year in which the SDGs were adopted (2014-15), almost one quarter of Pakistan’s population lived below the poverty line and over 38.8 percent population was multidimensionally poor. In March 2018, the Planning Commission prepared a summary with SDGs framework, with the baseline poverty figure of 29.50 percent of the population and aimed to reduce it to 9 percent in the year 2030. Similarly, the multidimensional poverty target was set from 38.8 percent to 19 percent.

The last two years have seen political change in Pakistan which followed change in economic policy and slowdown in economic growth. We have also seen the policy rate going up initially and then coming down a few months ago, significant depreciation of the rupee, and food inflation; all these factors were not helpful in reducing poverty and in fact added to the miseries of the poor. But it is certain that Covid-19 has a disproportionate effect and will have long-term implications on the jobs and income of the poor.

UNU-Wider estimates that the Covid-19 crisis could add 80-400 million new poor, living under $1.90 per day. These numbers may reverse the gains made over the last two decades in the fight against poverty. The estimates illustrate a resurgence of poverty in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Pakistan.

What this means is that people were just one shock away from poverty and may easily be prey to the current Covid crisis. This also means that one out of three children born in the year 2000, the year of MDGs, will still be living in poverty in 2030, the terminal year of the SDGs, if serious and targeted efforts are not made. We are not talking about shared prosperity and wellbeing, just about people having enough to eat for survival.

There are three major groups to form a cluster of poor. The rural landless labourer/tenant, urban informal or low wage workers, and women workers both in rural and urban areas. Given the slower pace of economic recovery this year, the only powerful policy instrument available with the government is augmenting the existing social protection programme. Pakistan’s SDGs target was to reach 70 percent of people living below the poverty line through social protection by 2030; this must be brought forward.

This poses a great challenge but also an opportunity. Challenge in the sense to have registration of all the people who need to be brought under a comprehensive social protection programme. But taking this challenge will be very instrumental for future targeted assistance programmes, once there is valid registration and list of people with a unique ID.

The other important policy measure could be to control the leakage, corruption and cartelization of essential commodities to neutralize the effect of market manipulation and artificial price hikes – especially in food items. Timely public-sector interventions in these areas along with quality assessment and research on the effect of macroeconomic policies on household level poverty can lead to evidence-based policymaking. Apolitical and objective analysis can show how exchange rate, policy rate, subsidies, trade, taxation, energy and fuel prices, and agriculture policy can help or cancel out social protection benefits.

Social protection benefits may help in poverty reduction if not supported with favourable macroeconomic policy measures – policies such as increase in indirect taxation, food inflation, rise in energy prices, increase in utilities bills, inadequate provision of public services such as education, health and water will cancel out the benefits.

If children born in the year 2000 remain poor in 2030 as adults and transmit poverty to the next generation, that demonstrates a collective failure and will inflict a moral wound on our conscience. Therefore, delaying poverty alleviation is not an option, despite the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic. We need to fight back with right policies, attaching high political priority, capitalizing on collective wisdom and forging partnership. A poverty-free Pakistan is achievable.

The writer is an Islamabad-based environmental and human rights activist.

-

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud -

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels -

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing -

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras -

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards -

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest -

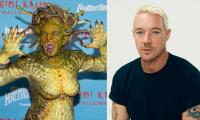

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween'

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween' -

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down -

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest?

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest? -

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights -

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed -

Hailey Bieber Shares How She Protects Her Mental Health While Facing Endless Criticism

Hailey Bieber Shares How She Protects Her Mental Health While Facing Endless Criticism -

Queen Elizabeth II Saw ‘qualities Of Future Queen’ In Kate Middleton

Queen Elizabeth II Saw ‘qualities Of Future Queen’ In Kate Middleton -

Amanda Seyfried Shares Hilarious Reaction To Discovering Second Job On 'Housemaid': 'Didn’t Sign Up For That'

Amanda Seyfried Shares Hilarious Reaction To Discovering Second Job On 'Housemaid': 'Didn’t Sign Up For That' -

Hilary Duff Reveals Deep Fear About Matthew Koma Marriage

Hilary Duff Reveals Deep Fear About Matthew Koma Marriage