Doused in love, humour and sorrow, fragrance of Ghalib’s letters still in the air

For generations, literature enthusiasts have cherished the fragrance of Mirza Ghalib letters, considered the best in Urdu prose, and there was a treat of this romantic delight on offer at The Second Floor on Wednesday evening.

Khalid Ahmed, known for his oratory skills, read letters of the most celebrated poet of Urdu literature, Ghalib, who had invented a style of prose that turned correspondence into conversation.

“You can talk with the tongue of a pen at a distance of some two thousand miles and enjoy, while physically separated, the dance of words in conversational union,” wrote Mirza Ghalib in one of his letters to Mirza Hatim Ali Baig.

Ahmed started off with Ghalib’s prose by reciting a letter written in a light-hearted tone, requesting the addressee to reply soon because unlike present times, there was no concept of instant responses, rather the sender counted the hours as they lapsed into days.

The letter did not ask much; rather it was a gentle reminder that Ghalib, who was usually busy responding to letters, was earnestly waiting for his friend’s reply.

Drawing parallels with Ghalib’s poetry, Wajid Jawad, a well-known publisher and a literature aficionado, read out from the Diwaan, hinting to an array he intends to publish by sorting couplets in accordance with themes like love, pleasure seeking in pain, difficulties and hypocrisy among others.

In a letter written to Baig, Ghalib attempted to console his friend on the death of his beloved’s demise and managed to add humour by saying that while most die in their own homes, there are few who are privileged to die in their beloved’s house. But he also drew comparison by choosing three people namely Hasan Basri, Firdausi and Majnoon as to one should look up to Basri to attain level of a dervish, to Firdaausi in terms of poetry and to Majnoon in the case of love.

Continuing with another letter, Ahmed added that when Baig became inconsolable, even after considerable time had passed, Ghalib penned another piece taking a jibe at the afterlife by saying that the company of just one lover there horrified him, hence Baig needed to move on and look for love again.

Known for converting letter-writing into a dialogue, another letter which focused on departure of a man from one city to another showed how grandeur can be added to mere domestic events.

But perhaps there was one letter which described how Ghalib grappled with his own existence - a small account of the devastation witnessed by Delhi following the War of Independence of 1857 and the rise of British soon afterwards.

With lines including, “Na Delhi, na Delhi walay, shehar sehra hogaya (There is no Delhi or its dwellers, the city has now become a desert)”, the poignant letter is simple yet casts a heavy impression on the listener as Ghalib mentions names and how those people were either shot or imprisoned.

Given that the poet saw the loss of glory and fall of tradition, a sense of nostalgia hangs in the air when he ends with the words, “Dehli kahan hai? Sab lut gaya hai (Where is Delhi? All has been lost)”.

For the audience, Ghalib’s letters, as the purest form of dialogue and communication, provided an escape from the virtual reality we live in today — a reminder that the originality and simplicity of human expressions coupled with linguistic aesthetics could help people experience life in its pure form.

-

Dave Filoni, Who Oversaw Pedro Pascal's 'The Mandalorian' Named President Of 'Star Wars' Studio Lucasfilm

Dave Filoni, Who Oversaw Pedro Pascal's 'The Mandalorian' Named President Of 'Star Wars' Studio Lucasfilm -

Is Sean Penn Dating A Guy?

Is Sean Penn Dating A Guy? -

Sebastian Stan's Godmother Gives Him New Title

Sebastian Stan's Godmother Gives Him New Title -

Alison Arngrim Reflects On 'Little House On The Prairie' Audition For THIS Reason

Alison Arngrim Reflects On 'Little House On The Prairie' Audition For THIS Reason -

Spencer Pratt Reflects On Rare Bond With Meryl Streep's Daughter

Spencer Pratt Reflects On Rare Bond With Meryl Streep's Daughter -

'Stranger Things' Star Gaten Matarazzo Recalls Uncomfortable Situation

'Stranger Things' Star Gaten Matarazzo Recalls Uncomfortable Situation -

Gaten Matarazzo On Unbreakable Bonds Of 'Stranger Things'

Gaten Matarazzo On Unbreakable Bonds Of 'Stranger Things' -

Beyonce, Jay-Z's Daughter Blue Ivy Carter's Massive Fortune Taking Shape At 14?

Beyonce, Jay-Z's Daughter Blue Ivy Carter's Massive Fortune Taking Shape At 14? -

Meghan Markle Fulfills Fan Wish As She Joins Viral 2106 Trend

Meghan Markle Fulfills Fan Wish As She Joins Viral 2106 Trend -

Selena Gomez Proves Point With New Makeup-free Selfie On Social Media

Selena Gomez Proves Point With New Makeup-free Selfie On Social Media -

John Mellencamp Shares Heartbreaking Side Effect Of Teddi's Cancer

John Mellencamp Shares Heartbreaking Side Effect Of Teddi's Cancer -

Kate Middleton 'overjoyed' Over THIS News About Meghan Markle, Prince Harry

Kate Middleton 'overjoyed' Over THIS News About Meghan Markle, Prince Harry -

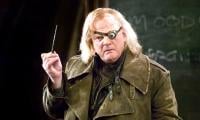

'Harry Potter' Star Brendan Gleeson Reluctantly Addresses JK Rowling's Trans Views

'Harry Potter' Star Brendan Gleeson Reluctantly Addresses JK Rowling's Trans Views -

Priscilla Presley Reveals The Path Elvis Would Have Taken If He Were Still Alive

Priscilla Presley Reveals The Path Elvis Would Have Taken If He Were Still Alive -

Kianna Underwood's Death Marks Fourth Nickelodeon-related Loss In Weeks, 9th Since 2018

Kianna Underwood's Death Marks Fourth Nickelodeon-related Loss In Weeks, 9th Since 2018 -

Hayden Christensen Makes Most Funny 'Star Wars' Confession Yet

Hayden Christensen Makes Most Funny 'Star Wars' Confession Yet