The making of Marxism

Four years ago, in these columns, I paid tribute to Marx by outlining his key ideas

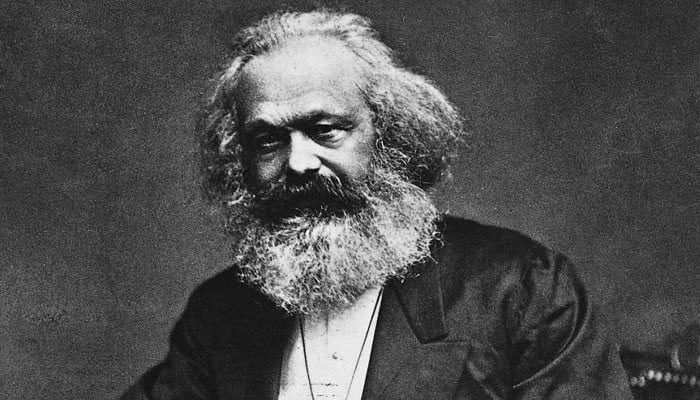

Time has scarcely dulled the power of Karl Marx’s ideas, whose 207th birthday the world marks today (May 5). His vision of a post-capitalist society is the ‘invisible hand’ behind much of China’s remarkable progress. President Xi Jinping acknowledged this at the 2018 World Conference on Marxism in Beijing. He said, “Our belief in the scientific truth of Marxism has not only profoundly changed the world but also transformed China.”

The impact of Marx’s ideas on China is unmistakable: food security, housing, quality education and healthcare for all are achievements made possible through economic planning. These are hallmarks of a politics that delivers tangible results.

In contrast, our blind faith in the mantra ‘business is not the business of the state’ has failed to deliver even a fraction of what China has accomplished. We ignore Marx’s ideas – ideas that hold extraordinary relevance today – and pretend China’s rise never happened, all while clinging to the false promises of trickle-down economics. As we shall see below, this path will not bring us progress.

Four years ago, in these columns, I paid tribute to Marx by outlining his key ideas. This time, I turn to the political and intellectual ferment of mid-nineteenth-century Europe – the crucible in which his ideas were forged – to unpack his worldview called Marxism, and bring out his landmark contribution.

Briefly put, Europe was in turmoil. Workers were in open revolt across France, Belgium and Poland; the rise of Chartism in England and demonstrations for national unity and freedom in Germany were part of a revolutionary tide that began with the 1789 French Revolution and was sweeping across Europe.

Meanwhile, the Junkers – the German waderas who ruled the land – were reclaiming their feudal privileges lost to Napoleon, while suppressing the democratic ideas that German intellectuals kept alive. Among them, the rationalism of Locke, Voltaire, and Kant gave rise to a powerful literary and philosophical current: the Aufklärung, or Enlightenment.

Marx imbibed this Aufklarung fully. His ideas, says Isaiah Berlin, derive their ‘structure and basic concepts from Hegel, their belief in the primacy of matter from Feuerbach, and their view of the proletariat (working class) from the French communist tradition.’

From Hegel, Marx took the dialectical method: “The object”, he said, “must be studied in its development, as something imbued with contradictions in itself”. From Saint Simon, he took the idea of socialism but stripped it of its utopian faith in education and benevolent rulers as vehicles of transformation. Instead, he rooted it in the people’s struggle for economic justice – the true ‘motor’ of history, unfolding with ‘iron necessity’ in events like the fall of feudalism in France in 1789, and the overthrow of capitalist rule in China in 1949. From Adam Smith, he took the idea of workers’ exploitation, that the “produce of labour does not belong to the laborer…it resolves into wages and profit.”

Other ideas that Marx engaged with include Rousseau’s claim that private property is the root of society’s ills; Morelly’s maxim, “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs", which is in our constitution (Article 3), and though diluted it is nevertheless ignored by those sworn to uphold it; Carlyle’s furious denunciation of capitalism: “Supply and demand is not the law of nature"; Sismondi’s insight into capitalism’s recurring economic crises; Ricardo’s recognition of class divisions and class struggle; Schiller’s condemnation of corruption and unearned privilege, and “the exploitation of man by man” with such passion, it is said, that it left Marx to only add scholarship.

From this ‘maze of confusion’, this dense chaos of ideas from German philosophy, French socialism and British political economy, Marx forged his worldview, synthesising and elevating them to a new level. He first articulated it with Friedrich Engels in The Communist Manifesto in 1848, when he was just 29 (and Engels was 28).

The Manifesto presents history as a succession of struggles by the oppressed people for economic justice. It argues that societies built on exploitation – be it slavery, feudalism, or capitalism – while once forward movements, eventually become obstacles to progress and must be replaced with one that keeps it going. It assigns the task of replacing capitalism with public ownership of key assets to the working class – a transformation we see unfolding in China.

This vision is summed up in Marx’s call: “Workers of the world unite… You have a world to win!”

Today, it resonates not only in China’s advance but globally – in Z A Bhutto’s promise of ‘Roti, Kapra aur Makan’ in Pakistan, in Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum’s slogan ‘For the good of all, first the poor’, in US congresswoman Ocasio Cortez’s fiery demand to ‘Fight oligarchy’, in Sri Lanka’s quest for ‘Political socialism: a people’s society’ under A K Dissanayake, in Nepal’s bold 'Prachanda Path’ under K P Oli, and Che Guevara’s immortal cry 'Venceremos – We will overcome!'

The writer is a freelance contributor. He can be reached at: Khwaja.Sarmad@gmail.com

-

Alicia Keys Celebrates 25 Years Of Breakout Single ‘Fallin’’

Alicia Keys Celebrates 25 Years Of Breakout Single ‘Fallin’’ -

Akinola Davies Jr. Gives His Immigrant Parents A Shoutout In 2026 BAFTAs Acceptance Speech

Akinola Davies Jr. Gives His Immigrant Parents A Shoutout In 2026 BAFTAs Acceptance Speech -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Told 'first Thing They Should Do' After Andrew Arrest

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Told 'first Thing They Should Do' After Andrew Arrest -

Jennifer Garner Reveals What Her Kids Think Of Her Acting Career

Jennifer Garner Reveals What Her Kids Think Of Her Acting Career -

Prince William Should Focus On 'family Business' After Andrew Blunder

Prince William Should Focus On 'family Business' After Andrew Blunder -

Katherine Schwarzenegger Pratt 'brought To Tears' By Sister-in-law's Gesture

Katherine Schwarzenegger Pratt 'brought To Tears' By Sister-in-law's Gesture -

Prince William Makes Bold Claim About Britain's Creative Industry At BAFTA

Prince William Makes Bold Claim About Britain's Creative Industry At BAFTA -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Insulting 'catchphrase' That Degarded Staff

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Insulting 'catchphrase' That Degarded Staff -

Kate Middleton, Princess Beatrice 'undercurrent Tension' Comes To Surface

Kate Middleton, Princess Beatrice 'undercurrent Tension' Comes To Surface -

'Grey's Anatomy' Alum Katherine Heigl Reveals Why She Stayed Silent After Eric Dane Loss

'Grey's Anatomy' Alum Katherine Heigl Reveals Why She Stayed Silent After Eric Dane Loss -

Host Alan Cumming Thanks BAFTAs Audience For Understanding After Tourette’s Interruption From Activist

Host Alan Cumming Thanks BAFTAs Audience For Understanding After Tourette’s Interruption From Activist -

Jennifer Garner Reveals Why Reunion With Judy Greer Makes Fans 'lose Their Minds'

Jennifer Garner Reveals Why Reunion With Judy Greer Makes Fans 'lose Their Minds' -

Chris Hemsworth Makes Shocking Confession About His Kids' Reaction To His Fame

Chris Hemsworth Makes Shocking Confession About His Kids' Reaction To His Fame -

Wiz Khalifa Reveals Unconventional Birthday Punch Tradition With Teenage Son In New Video

Wiz Khalifa Reveals Unconventional Birthday Punch Tradition With Teenage Son In New Video -

BAFTAs 2026: Kerry Washington Makes Debut In Custom Prada Gown

BAFTAs 2026: Kerry Washington Makes Debut In Custom Prada Gown -

Jennifer Lopez Gets Emotional As Twins Max And Emme Turn 18

Jennifer Lopez Gets Emotional As Twins Max And Emme Turn 18