Agriculture without farmers

With the passing of the United Nations’ highly contested Food Systems Summit last month, the task of “feeding the world” has taken on a newfound urgency.

But one point apparently lost on the summit’s attendees is that the project of ‘agricultural modernisation’ which many of them have supported for decades is only making food insecurity worse in recent years, especially in Africa.

Since the 2007-08 world food price crisis, Western governments and philanthropies, led by the United States and the Gates Foundation, have backed a multitude of programmes across the continent to raise farmers’ productivity and connect them to commercial supply chains. Together, these efforts carry the banner of an ‘African Green Revolution’ -- an approach not unlike the primarily Asian and Latin American Green Revolution before it.

But at the heart of this massive philanthropic and governmental undertaking lies an essential contradiction: agricultural ‘modernisation’, we are told, will benefit Africa’s smallholder farmers by giving advantages to farmer-entrepreneurs with larger landholdings. The result is a ‘revolution’ ostensibly meant to help the poor which actually makes rural life difficult for anyone but the most well-off, well-connected, commercially-oriented, and ‘efficient’ business people.

In our research, we have both encountered the reality of the African Green Revolution in Ghana, a country that has experienced a surge in agricultural foreign aid in recent years.

As geography professors Hanson Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Rachel Bezner Kerr have mentioned in their 2015 paper, British colonialists developed production and market systems to extract cocoa – a crop not widely consumed in the country but which continues to attract significant investment and subsidies today. In the post-colonial period of the 1960s and 1970s, the government of Ghana, with support from Western government donors, introduced high-yielding varieties of rice and maize, as well as imported chemical fertilisers.

In a 2011 paper, University of Ghana professor and anthropologist Kojo Amanor also explains, that from 1986 to 2003, Sasakawa Global 2000, a development organisation founded by Japanese industrialist Ryoichi Sasakawa and Norman Borlaug, the initiator of the Asian Green Revolution, tried unsuccessfully to bring new farm technology to rural Ghana and much of sub-Saharan Africa. Sasakawa Global 2000 took over the government’s previous role, distributing low-interest credit packages to smallholders willing to buy hybrid seed, chemical fertiliser and other agrochemicals, and become part of global, commercial supply chains.

Sasakawa Global 2000 found many farmers willing to accept their assistance. But according to Amanor, many of the farmers who initially adopted the technology reverted to traditional practices and local seed varieties after the project concluded. Even after years of working in rural Ghana, the organisation saw only a 45 percent recovery in crop investment.

These days, there are many reasons why smallholders do not cooperate with the “modernisation” programmes of the African Green Revolution. In their 2015 study, Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner Kerr found that smallholder farmers often preferred to plant their own maize varieties, even when government and development organisations made more ‘advanced’ hybrids available.

As the farmers understood well, their own hardier, local varieties of maize were more resistant to drought, required less labour, cost less, and required little or no chemical fertiliser. Moreover, unlike hybrids, whose wide leaves obstruct the sun for neighbouring plants, farmers could plant their own maize varieties alongside peanuts, cowpea, and bambara beans – all nutritious crops well adapted to the local ecology.

Development planners have long touted technologies like hybrid seeds as “solutions” to the many problems resulting from climate change, and it is true farmers sometimes turn to them in their struggle to adapt to unpredictable ecological conditions. In one study, one of us found that many smallholders in an area of northern Ghana reluctantly turned to those technologies in a desperate gambit to adapt to increasingly erratic rainfall, shortening growing seasons and drier, less fertile soils.

But beyond climate change, farmers have also adopted technology to deal with the problems induced by the African Green Revolution itself, such as increasing competition for land, as local businessmen (and they are overwhelmingly men) acquire farms to capitalise on the very programmes supposedly meant to help smallholders.

Excerpted: ‘African agriculture without African farmers’ Aljazeera.com

-

Prince Harry Secretly Reaches Out To King Charles, William Amid Andrew Scandal?

Prince Harry Secretly Reaches Out To King Charles, William Amid Andrew Scandal? -

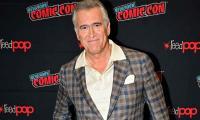

Bruce Campbell Makes Heartbreaking Statement As He Releases Details Of Cancer Diagnosis

Bruce Campbell Makes Heartbreaking Statement As He Releases Details Of Cancer Diagnosis -

Kaley Cuoco Reveals How She Felt On The Set Of 'Charmed'

Kaley Cuoco Reveals How She Felt On The Set Of 'Charmed' -

‘Mouse Utopia’ Collapse Shows The Need For Space Colonies, Says Elon Musk

‘Mouse Utopia’ Collapse Shows The Need For Space Colonies, Says Elon Musk -

Kate Middleton Sends Powerful Message To King Charles Amid Olive Branch To Meghan Markle, Harry

Kate Middleton Sends Powerful Message To King Charles Amid Olive Branch To Meghan Markle, Harry -

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle Mark Major Milestone With Powerful Message

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle Mark Major Milestone With Powerful Message -

'Emmerdale' Actor Eric Allan Breathes His Last After Incredible 48-year Career

'Emmerdale' Actor Eric Allan Breathes His Last After Incredible 48-year Career -

Prince William 'already King Unofficially' Amid Charles Abdication Plans

Prince William 'already King Unofficially' Amid Charles Abdication Plans -

FBI Hunts For Another High-profile Missing Case After Nancy Guthrie Disappearance

FBI Hunts For Another High-profile Missing Case After Nancy Guthrie Disappearance -

Carrie Underwood Unleashes Fierce Response After Unfortunate Incident On 'American Idol'

Carrie Underwood Unleashes Fierce Response After Unfortunate Incident On 'American Idol' -

Meta Tests AI Shopping Feature To Compete With ChatGPT And Gemini

Meta Tests AI Shopping Feature To Compete With ChatGPT And Gemini -

Prince Harry’s Claims About Prince William Fight Get Exposed: ‘The Truth Is Different’

Prince Harry’s Claims About Prince William Fight Get Exposed: ‘The Truth Is Different’ -

Savannah Guthrie Continues To Receive Support From Meghan Markle's Close Friend

Savannah Guthrie Continues To Receive Support From Meghan Markle's Close Friend -

Alan Cumming's Unexpected Gesture Comes To Light As He Blasts BAFTA For Tourette’s Incident

Alan Cumming's Unexpected Gesture Comes To Light As He Blasts BAFTA For Tourette’s Incident -

Global Oil, Gas Shipping Costs Soar As Iran Warns Of Strait Of Hormuz Closure

Global Oil, Gas Shipping Costs Soar As Iran Warns Of Strait Of Hormuz Closure -

Beyond The Smartphones: Qualcomm CEO Sees Robotics As Top Growth Engine By 2028

Beyond The Smartphones: Qualcomm CEO Sees Robotics As Top Growth Engine By 2028