A case for bilingual legislation

Pakistan must not remain a postcolonial exception in the global pursuit of linguistic justice

Successive governments in Pakistan have begun their respective tenures with lofty policies aimed at good governance, poverty eradication, universal literacy and the provision of healthcare and other basic services.

Any government invariably requires legislation to implement its policies. A policy may be well-intentioned and based on good faith, but if the accompanying legislation is not properly drafted in clear and accessible language, it can lead to severely adverse outcomes and ultimately be seen as a failure of both the policy and the government.

Therefore, there is a pressing need for the effective drafting of legislation to ensure the proper implementation of government policies and to bring about both qualitative and quantitative social change. Despite this need, no meaningful effort has been made to modernise legislative drafting in Pakistan. Much of our legislation still follows the British model, relying on techniques from 19th-century British India. It is written in legalese, passive voice, and complex English, making it difficult even for lawyers and judges to comprehend and interpret.

There is an urgent need to introduce modern thinking and ideas into legislative drafting. The concept of law has evolved – from a tool of oppression to a means of economic, social, and political development. However, legislative drafting techniques in Pakistan have not kept pace with this change.

The history of law is inextricably bound to the history of language addressed to the people or a section of people. From Hammurabi’s Code etched in stone to Magna Carta written in Latin, the legal word has always carried not only power but also identity. Language in governance is not a mere technicality but the vehicle through which rights are understood, duties are performed, and justice is claimed.

In democracies, the language of the law must belong to the people. Yet in Pakistan, it remains largely alien to them. More than 77 years after independence, Pakistan continues to operate under a colonial linguistic framework in its legal system. Despite the clear mandate of the constitution – stating that Urdu shall replace English as the official language – English remains the de facto language of legislation, judicial pronouncements, and administrative directives. This dissonance between the language of the state and the language of the people has produced not only a legal elite but also a widespread sense of exclusion among citizens who are governed by laws they cannot read or comprehend.

In this backdrop, a bilingual legislative system – in which laws are drafted, published and interpreted in both English and Urdu simultaneously, with equal legal authority – is more than a procedural reform. Such a framework would not only preserve the technical precision of English but also extend the accessibility, resonance, and relevance of Urdu to the legal experience of the broader population. In this regard, the constitutional foundation for a national legal language in Pakistan is unequivocal.

Statutes, constitutional amendments and subordinate legislation are drafted almost exclusively in complex English, while judgments, official communication, transaction documents and official gazettes reflect a persistent colonial hangover of complex English. In the past five decades, the plain language movement has changed legislation worldwide by using clear, concise and understandable language, avoiding jargon and technical terms unless absolutely necessary. This is to effectively use the universal legal doctrine that ignorance of law is not an excuse.

The United States Congress has even made it a law, ‘The Plain Writing Act of 2010’ that mandates federal public functionaries to use plain English. This improves the effectiveness and accountability of public servants by ensuring the public can easily understand and use laws and official communications.

This linguistic dissonance stands in stark contrast to the constitutional intent and has effectively marginalised a vast majority of the population. There is widespread ignorance of the law in Pakistan. Recognising this disconnect in 2015, the Supreme Court, headed by the then Chief Justice Jawwad S Khawaja, directed federal and provincial governments to implement Urdu as the official language without further delay. The nine-point judgment emphasised the constitutional violation caused by the continued use of English in official domains and mandated that laws, policies, and judgments be issued in Urdu.

Yet, a decade later, the directive remains largely unimplemented. The resistance lies in institutional inertia and the absence of structured legal mechanisms and infrastructure to support such a transition. A lack of standardised legal terminology in Urdu, insufficient training of legal professionals in bilingual drafting, and fears of compromising the exclusive domain of legalese have collectively hindered progress. Again, it was Justice Jawwad S Khawaja who spearheaded the availability of laws in plain Urdu (suo-motu case No 1 of 2005), which perhaps is still pending in the apex court.

Comparative global experiences offer compelling evidence that multilingual or bilingual legislative frameworks are instrumental in enhancing democratic participation, legal accessibility and knowledge of rights. India and Bangladesh, in our region, adopted bilingual legislation while Sri Lanka adopted a trilingual legal structure.

In Western democracies, linguistic pluralism in legislation is institutionalised. Canada enacts all federal laws in English and French. Switzerland recognises four national languages, and the European Union operates a multilingual legislative regime across 24 official languages. These systems reflect a commitment to linguistic justice, civic participation and equality before the law. Pakistan, by contrast, continued the dominance of complex English in law that alienated the vast majority of the population from governance and rule of law. Most Pakistanis cannot read or understand the laws that govern them, leading to a disconnect that undermines rule of law and democratic engagement.

Laws that are unintelligible are unjust. A bilingual system would help reduce this legal illiteracy. Police officers, local officials, teachers, students, and everyday citizens would be able to engage more fully with the legal framework that shapes their lives. Apart from that, the educational implications are quite profound. Bilingual legal texts can broaden the reach of legal education, making it more accessible to students who are fluent in Urdu but not in English. Civil society groups, activists and community organisers can use Urdu-language laws to spread awareness of rights and responsibilities.

Implementing Urdu in legislative drafting would also encourage the development of legal scholarship in the national language. A bilingual legal system that values both plain language English’s precision and Urdu’s reach can also create a more cohesive national identity – one that honours the educated elite and empowers the grassroots equally.

In this regard, Pakistan must adopt a multi-tiered institutional roadmap. Parliament must take the lead by developing comprehensive legal lexicons in Urdu and overseeing drafting and translation standards. Universities and law schools should initiate specialised programmes in legal translation, comparative drafting, and plain legal writing in both English and Urdu. Judicial academies, bar councils and bar associations must incorporate bilingual training into their curricula for judges, lawyers and legislative drafters.

The move towards a bilingual legislative system is not just a policy innovation but a moral and constitutional imperative. Language, in the context of law, is a reflection of who is seen, who is heard, and who it belongs. A legal order that speaks only to the privileged fails to fulfill its democratic promise.

Pakistan must not remain a postcolonial exception in the global pursuit of linguistic justice. A bilingual legislative framework would help reclaim the spirit of justice envisioned in 1973 by bridging the divide between the courtroom and the common citizen and between the constitution and the citizen. This is not merely a reform. It is a reclamation – of voice, of dignity, and of the right to understand and shape the laws that govern us. In the words of a very recent judgment of the Indian Supreme Court “Let us make friends with Urdu...".

The writer is a legal consultant.

-

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame -

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus -

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’ -

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter -

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud -

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels -

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing -

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras -

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards -

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest -

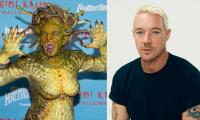

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween'

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween' -

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down -

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest?

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest? -

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights -

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed