Karachi has been sprawling in total absence of urban planning: Arif Hasan

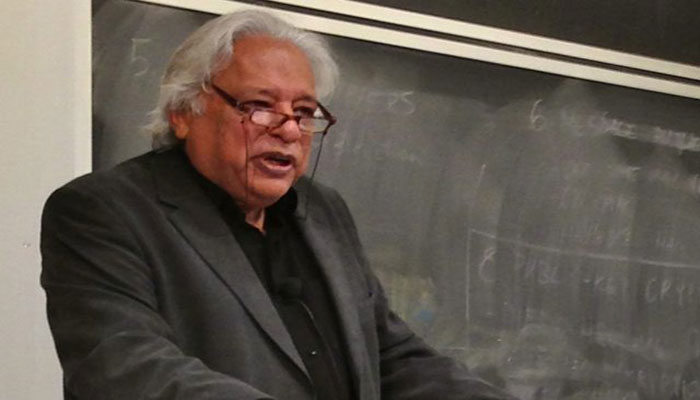

In total absence of any urban planning or strategy, the sprawling city of Karachi has been governed on an ad hoc basis, said urban planner Arif Hasan on Thursday.

Speaking on the third and the last day of the ‘8th International Conference on Karachi’ at the IBA, Hasan was addressing a session titled ‘What I have learnt in 45 years about urban planning of Karachi through participation, voyeurism, disillusionment, love, hope and affection’. He presented the reasons behind the ill-planning in the metropolis.

“A city of 0.4 million all of a sudden was inducted with 0.6 million population,” he said explaining a population boom in Karachi following Pakistan came into being in 1947. For six years at least the issue was to get the migrators settled; although they were all rehabilitated, he said, it became a culture to making settlements in the city. “We never fulfilled the required necessities of the city,” he said adding that only houses were constructed that too for rich people.

The port city

In 1951, Karachi’s port activities were 2.8 million ton and 95 per cent of which was through railways. Karachi’s port activity in 2019 was 41.8 million tons and 96 per cent of which was through road, he said.

The consumption of one unit of energy, for one unit of road, for the delivery of one ton, means the ratio is one to one, he added. However, with rail, the ratio can be one to 15 and through the sea, it could be one to 40. For this purpose, he said, one inland water navigation policy was deliberated in detail. That option was in front of generals when the National Logistic Cell was formed. “But they made a very wrong decision which had its severe repercussions. Roads were damaged, price of mobility increased and till today we are coping that loss.”

This city needed cargo terminal, he explained. “We never designed it. Wherever one found space, they were constructed,” he said adding that bus terminals and warehouses were constructed in a similar manner. All these, he said, were done in a stopgap manner. “There was no bus stops or terminals for private sector buses, they made it themselves wherever they found a spot and the city continued to develop. This needs to be understood that the city isn’t dead. It is living,” he said adding that if you don’t get what it needs, it makes its own way.

These things, he said, weren’t understood by courts as they ordered to demolish all planned settlements, which obviously couldn’t be done and the authorities only resorted to demolishing structures and settlements of few of the poor areas and projected as if something had been achieved. “Even for the posh settlements, there was no planning for education, recreation and health sectors. The residential areas are also encroachments, as they encroach on commercial areas but they weren’t touched.”

He continued: “Karachi is not in the need of dismantlement, what it needs is correction, reorganisation,” he said adding that it is termed as “special reorganisation,” but nothing had worked on this concept. “One government official, Malik Zaheer, tried to work on this concept, but the political leadership didn’t support him, because the financial and commercial facilities don’t emerge in a way as they emerge in redevelopment,” he said.

Land use plan

The only land use plan this city has been speculation, he said.

Hasan said there were 0.45 million plots vacant in this city since the last 30 years. In the year 2012, Hasan was told by the Sindh Building Control how 0.2 million flats were under construction and above 0.1 million were lying vacant. He shared how 15,000 hector mangroves and 2,800 villages had disappeared from the face of the earth in Karachi. This he got to know through satellite images through Parveen Rehman’s work.

In the year 1985, he said 70 per cent of the vegetables and fruits for Karachi used to be grown in its own villages, which was reduced to 10 per cent in the year 2013, as some 60 billion cubic feet gravel had been dug out from the city’s rivers for the construction due to which their aquifers had disappeared. The 62 per cent of the city population, he said, was living in unofficial settlements of the 30 per cent of the city’s area, whereas, the 26 per cent population was living on the rest of the 70 per cent land.

Law and justice

“The law doesn’t provide justice,” he said adding that it was because the lawmakers were “the enemies of the poor”.

He said around one million to 1.5 million people were deprived of their homes in Pakistan, conservatively.

“In Sindh’s Bandar and Badu Island of 120 kilometres, there are 3,500 hectares of the jungle where a development scheme of Rs50 billion came forward,” he said. For the construction of the Karachi Circular Railway, the Badu Island development scheme and the width of rain drains, he pointed out that some 60 to 65 thousand households would be affected.

For the construction of the Lyari Expressway, he said, 3,286 students couldn’t appear for their matric, pre-matric and intermediate examinations during their dislocation. After that, a former commissioner of the project, Shafiq Paracha, had decided that the encroachments would be only removed in the city after the final exams, he added.

However, after the recent court order, only encroachments in poor areas were removed, whereas “encroachments of the Sindh government, the Supreme Court itself and those in power were not removed”, he said.

The street economy suffered a loss of 1.5billion in four months when 9,000 kiosks and 20,000 street vendors were removed, he said. “All these could have been regularised; there could have been a solution,” he stressed. When all these poor settlements were being removed, the court at the same time, regularised development schemes surrounding the prime minister’s residence in Bani Gali. “This was the time when the KCR’s mutasareen [affectees] were willing to get their settlement regularised or demanded some alternative,” he pointed out.

Planning

“The plan is as good as the institution that implements it,” he said.

For the Katchi Abadi Improvement and Regularisation programme, he said, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank had given massive funds in the 90s in which they were regulating one per cent of the population every year.

-

Timothee Chalamet Admits To Being Inspired By Matthew McConaughey's Performance In 'Interstellar'

Timothee Chalamet Admits To Being Inspired By Matthew McConaughey's Performance In 'Interstellar' -

'Determined' Savannah Guthrie Plans To Honour Her Mother Nancy With Major Move: 'It's Going To Be Emotional'

'Determined' Savannah Guthrie Plans To Honour Her Mother Nancy With Major Move: 'It's Going To Be Emotional' -

Train's Pat Monahan Blows The Lid On 'emotional' Tale Attached To Hit Song 'Drops Of Jupiter'

Train's Pat Monahan Blows The Lid On 'emotional' Tale Attached To Hit Song 'Drops Of Jupiter' -

Kurt Russell Spills The Beans On His Plans For Milestone Birthday This Year: 'Looking Forward To It'

Kurt Russell Spills The Beans On His Plans For Milestone Birthday This Year: 'Looking Forward To It' -

PayPal Data Breach Exposed Sensitive User Data For Six-month Period; What You Need To Know

PayPal Data Breach Exposed Sensitive User Data For Six-month Period; What You Need To Know -

Prince William Receives First Heartbreaking News After Andrew Arrest

Prince William Receives First Heartbreaking News After Andrew Arrest -

11-year-old Allegedly Kills Father Over Confiscated Nintendo Switch

11-year-old Allegedly Kills Father Over Confiscated Nintendo Switch -

Jacob Elordi Talks About Filming Steamy Scenes With Margot Robbie In 'Wuthering Heights'

Jacob Elordi Talks About Filming Steamy Scenes With Margot Robbie In 'Wuthering Heights' -

Why Prince Harry Really Wants To Reconcile With King Charles, Prince William, Kate Middleton?

Why Prince Harry Really Wants To Reconcile With King Charles, Prince William, Kate Middleton? -

'Grief Is Cruel': Kelly Osbourne Offers Glimpse Into Hidden Pain Over Rockstar Father Ozzy Death

'Grief Is Cruel': Kelly Osbourne Offers Glimpse Into Hidden Pain Over Rockstar Father Ozzy Death -

Timothée Chalamet Reveals Rare Impact Of Not Attending Acting School On Career

Timothée Chalamet Reveals Rare Impact Of Not Attending Acting School On Career -

Liza Minnelli Gets Candid About Her Struggles With Substance Abuse Post Death Of Mum Judy Garland

Liza Minnelli Gets Candid About Her Struggles With Substance Abuse Post Death Of Mum Judy Garland -

'Saturday Night Live' Star Will Forte Reveals How He Feels About Returning To The Show After 2010 Exit

'Saturday Night Live' Star Will Forte Reveals How He Feels About Returning To The Show After 2010 Exit -

Police Officer Arrested Over Alleged Assault Hours After Oath-taking

Police Officer Arrested Over Alleged Assault Hours After Oath-taking -

Maxwell Seeks To Block Further Release Of Epstein Files, Calls Law ‘unconstitutional’

Maxwell Seeks To Block Further Release Of Epstein Files, Calls Law ‘unconstitutional’ -

Prince William Issues 'ultimatum' To Queen Camilla As Monarchy Is In 'delicate Phase'

Prince William Issues 'ultimatum' To Queen Camilla As Monarchy Is In 'delicate Phase'