‘East India Company set the trend of influencing lawmakers to boost business’

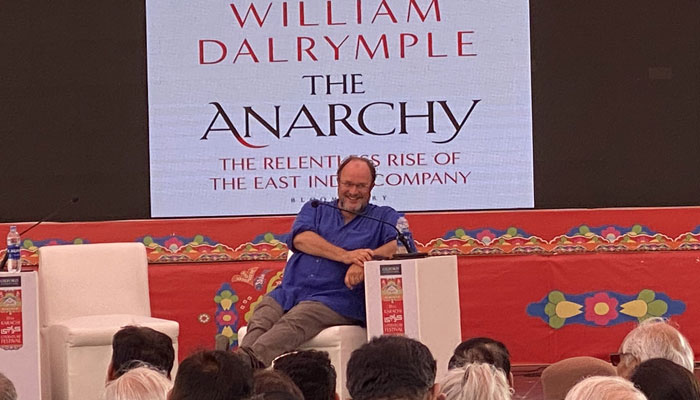

In a gathering of hundreds of people at the 11th Karachi Literature Festival being held at a local hotel in Karachi, historian William Dalrymple, as he introduced his latest book ‘The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of The East India Company’, said the East India Company that comprised of a bunch of merchants could rule over India because of its remarkable military talents.

He said the company exploited the locals, influenced the laws, occupied land and collected huge taxes to generate more and more revenue for its businesses. He maintained that it was the East India Company that set the trend of making laws and influencing policymakers to boost its businesses. This trend is still a sign of capitalism and colonialism, he said.

The session was moderated by his colleague George Fulton, a British-Pakistani television journalist and producer. Dalrymple narrated many remarkable stories of the Subcontinent’s history from his book.

Expansion of the East India Company

Shedding light on the establishment of the British Raj in India, he mentioned that Robert Clive, who was an accountant of the East India Company, for the first time established political and military supremacy of the company in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, and laid the foundations of the British rule in India.

Later, Warren Hastings, who was the first governor of the presidency of Fort William, the head of the Supreme Council of Bengal, and the de facto first governor general of India from 1773 to 1785 fought against the plunder of Bengal by his colleagues. However, his feud with Philip Francis led to charges of corruption against him, after which British Parliament impeached him. However, after a long and very public trail, he was finally acquitted in 1795.

Philip Francis replaced Hastings from 1794 until his death. Having failed to kill Hastings in a duel, he returned to London where his accusations eventually led to the impeachment of both Hastings and his Chief Justice Elijah Impey. Both were ultimately acquitted.

Digging into the past, the author mentioned; “Having surrendered British forces in North America to a combined American and French force at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, Cornwallis was recruited as Governor General of India by the East India Company to stop the same happening there. A surprisingly energetic administrator, he introduced the permanent settlement, which increased company land revenues in Bengal, and defeated Tipu Sultan in the 1782 Third Anglo-Mysore War.”

The author, however, said Richard Colley Wellesley was the governor general of India who became the first person to conquer more of India than what Napoleon could do in Europe. Despising the mercantile spirit of the East India Company, and answering instead to the dictates of his Francophobe friend Dundas, being the president of the Board of Trade he used the East India Company's armies and resources successfully to wage the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, which ended with the killing of Tipu Sultan and the destruction of his capital in 1799. Later, he fought the Second Anglo-Maratha War, which led to the defeat of the armies of both Scindia and Holkar in 1803.

By this time, he had expelled the last French units from India and achieved the East India Company’s control of most of the subcontinent south of the Punjab.

Dalrymple explained that Colonel Arthur Wellesley, then governor of Mayosre and chief military and political officer in the Deccan played an important role in defeating the armies of Tipu in 1799 and 1803. He also defeated Maratha armies of Hindustan with help of his Commander in Chief Gerald.

French expulsion

Joseph-Francois Dupleix, who was the governor general of the French establishments in India, lost the Carnatic Wars in southern India to the young Robert Clive. Likewise, the last French man was General Peirre Culiller-Perron who lived with his troops hundreds miles to the south-east of Delhi in the great fortress of Aligarh, but in 1803 betrayed his men in return for a promise by the company to let him leave India safely.

The Mughals and Company

Defining the Mughal era in India, the author said Aurangzeb Alamgir’s was a charmless and puritanical Mughal emperor, whose overly ambitious conquest of the Deccan first brought Mughal dominions to their wide extent but then also led to their eventual collapse. The alienation of the Hindu population, especially the Rajput allies, during his rule due to his religious bigotry accelerated the collapse of the empire after his death.

Later, Muhammad Shah Rangila’s lack of military talent led to his defeat by Persian warlord Nader Shah at the Battle of Karnal in 1739. Nader looted Delhi, taking away with him the Peacock Throne, into which was embedded the legendary Koh-i-Noor diamond. He returned to Persia, leaving Muhammad Shah as a powerless king with an empty treasury. The Mughal Empire was bankrupt and was fractured beyond repair, he said.

While narrating stories of the Mughal emperors, the author was of the view that their internal clashes led to the collapse of their empire. However, Shah Alam, who was a talented Mughal prince, fought the company at Patna and Buxar.

About the notorious Nawab Mir Jafar, he said Jafar was an uneducated Arab soldier. He had played his part in many of Aliverdi's most crucial victories against the Marathas, and led the successful attack on Calcutta for Sirajud Daula in 1756. He joined the conspiracy hatched by the Jagat Seths to replace Sirajud Daula with his own rule, and soon found himself the puppet ruler of Bengal at the whim of the East India Company. Robert Clive rightly described him as 'a prince of little capacity'.

Later, Mir Qasim conspired with the company to replace the incompetent Jafar in a coup in 176o and succeeded in creating a tightly run state with a modern infantry army. But within three years, he also ended up in a conflict with the company and in 1765 what remained of his forces were finally defeated at the Battle of Buxar. He fled westwards and died in poverty near Agra.

He mentioned that Tipu Sultan, who was able to defeat the East India Company in several campaigns, most notably alongside his father Haidar Ali, at the Battle of Pollilur in 1780. He succeeded his father in 1782 and ruled with great efficiency and imagination during peace, but with great brutality in war. He was forced to cede half his kingdom to Lord Cornwallis's Triple Alliance with the Marathas and Hyderabadis in 1792 and was finally defeated and killed by Lord Wellesley in 1799.

About the Maratha rulers, the author highlighted the role of Jaswant Rao and said that he was the illegitimate son of Tukoji Holkar by a concubine. A remarkable war leader, he showed less grasp of diplomacy and allowed the East India Company fatally to divide the Maratha Confederacy, defeating Scindia first and then forcing him into surrender the following year. This left the company in possession of most of Hindustan by the end of 18o3.

Conclusion

The author concluded the session with remarks that the East India Company troops were forced into what we would now call an act of involuntary privatisation. They dismissed Mughal revenue officials in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and replaced them with a set of English traders. The collecting of Mughal taxes was henceforth subcontracted to a powerful multinational corporation — whose revenue-collecting operations were protected by its own private army.

The Company had been authorised by its founding charter to wage war and had been using violence to gain its ends since it boarded and captured a Portuguese vessel on its maiden voyage in 1602.

Moreover, they had controlled small areas around its Indian settlements since the 163os. Nevertheless, 1765 was really the moment when the East India Company ceased to be anything even distantly resembling a conventional trading corporation, dealing in silks and spices, and became something within a few months that recruited local Indian soldiers. An international corporation was in the process of transformation into an aggressive colonial power, the historian remarked.

The Victorians thought the most important aspect of history was the politics of the nation state, he said, adding that rather than giving importance to the economics of corrupt corporations, they believed their politics was the fundamental unit of study and the real driver of transformation in human affairs.

Moreover, they liked to think of the empire as a mission civilisatrice: a benign national transfer of knowledge, railways and the arts of civilisation from the West to the East, and there was a calculated and deliberate amnesia about the corporate looting that opened the British rule in India.

He said his book did not aim to provide a complete history of the East India Company, still less an economic analysis of its operations. Instead, it was an attempt to answer the question of how a single business operation, based in one London office complex, managed to replace the mighty Mughal Empire as masters of the vast Subcontinent between the years 1756 and 1803.

The book tells the story of how the company defeated its principal rivals - the nawabs of Bengal and Avadh, Tipu Sultan's Mysore Sultanate and the great Maratha Confederacy - to take under its own wing the Emperor Shah Alam, a man whose fate it was to witness the entire story of the Company's rise from a humble trading body to a fully-fledged imperial power.

The company's many wars and its looting of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa hugely added to this disruption, and in regions very far from Delhi, he said.

Later, he autographed copies of his book purchased by people at the event.

-

EU Rejects Any Rise In US Tariffs After Court Ruling, Says ‘a Deal Is A Deal’

EU Rejects Any Rise In US Tariffs After Court Ruling, Says ‘a Deal Is A Deal’ -

King Charles Congratulates Team GB Over Winter Olympics Success

King Charles Congratulates Team GB Over Winter Olympics Success -

Meryl Streep Comeback In 'Mamma Mia 3' On The Cards? Studio Head Shares Promising Update

Meryl Streep Comeback In 'Mamma Mia 3' On The Cards? Studio Head Shares Promising Update -

Woman Allegedly Used ChatGPT To Plan Murders Of Two Men, Police Say

Woman Allegedly Used ChatGPT To Plan Murders Of Two Men, Police Say -

UK Seeks ‘best Possible Deal’ With US As Tariff Threat Looms

UK Seeks ‘best Possible Deal’ With US As Tariff Threat Looms -

Andrew Arrest Fallout: Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Face Demands Over Dropping Royal Titles

Andrew Arrest Fallout: Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Face Demands Over Dropping Royal Titles -

Rebecca Gayheart Breaks Silence After Eric Dane's Death

Rebecca Gayheart Breaks Silence After Eric Dane's Death -

Kate Middleton 2026 BAFTA Dress Honours Queen Elizabeth Priceless Diamonds

Kate Middleton 2026 BAFTA Dress Honours Queen Elizabeth Priceless Diamonds -

Sterling K. Brown's Wife Ryan Michelle Bathe Reveals Initial Hesitation Before Taking On New Role

Sterling K. Brown's Wife Ryan Michelle Bathe Reveals Initial Hesitation Before Taking On New Role -

BAFTA Film Awards Winners: Complete List Of Winners

BAFTA Film Awards Winners: Complete List Of Winners -

Millie Bobby Brown On Her Desire To Have A Big Brood With Husband Jake Bongiovi

Millie Bobby Brown On Her Desire To Have A Big Brood With Husband Jake Bongiovi -

Backstreet Boys Admit Aging Changed Everything Before Shows

Backstreet Boys Admit Aging Changed Everything Before Shows -

Biographer Exposes Aftermath Of Meghan Markle’s Emotional Breakdown

Biographer Exposes Aftermath Of Meghan Markle’s Emotional Breakdown -

Ryan Coogler Makes Rare Statements About His Impact On 'Black Cinema'

Ryan Coogler Makes Rare Statements About His Impact On 'Black Cinema' -

Rising Energy Costs Put UK Manufacturing Competitiveness At Risk, Industry Groups Warn

Rising Energy Costs Put UK Manufacturing Competitiveness At Risk, Industry Groups Warn -

Kate Middleton Makes Glitzy Return To BAFTAs After Cancer Diagnosis

Kate Middleton Makes Glitzy Return To BAFTAs After Cancer Diagnosis