Our moral blind spot

Legal eye

The writer is a lawyer based in

Islamabad.

Our state and society appear to have reached a consensus over the role of fundamental human rights guaranteed by our constitution: they are not inalienable entitlements of citizens but a luxury that can be offered only after the state overcomes its security challenges.

The resilience that we claim to have developed in the face of terror has made us nonchalant about the need to preserve human life. Lives are now valued in approximations: if the margin of error in the lives being taken by the state is less than 5-10 percent, it is good enough.

This week the Supreme Court dismissed appeals of convicts who had been handed the death penalty by military courts. There is nothing remarkable about this decision. It was expected after the apex court held in the 21st Amendment cases that military courts trying civilians was problematic neither from a human rights nor a separation of powers perspective. That decision will remain a spot on our jurisprudence and will need to be undone one day when we are able to come out of our present deeply entrenched militarised mindset.

The thinking behind the 21st Amendment cases could have been that when there has emerged a national consensus on how to fight militancy and terror, with military courts and trials in secrecy being part of such consensus, it is not for the courts to refuse to give effect to the consensus on a matter of national policy. That it is not the court’s business to tell the executive branch how to fight a war or to tell the legislative branch what ought to be the content of the constitution. Unfortunately the court didn’t say any of this.

What it essentially said was that it has the power to strike down a constitutional amendment, if need be, and could thus override a supermajority decision reached by parliament. But that it wouldn’t strike down the 21st Amendment establishing military courts, as military courts trying civilians behind a veil of secrecy wasn’t abhorrent to the principles and values enshrined in our constitution. The 21st Amendment decision had thus left very limited room for judicial review only on three grounds: coram non judice, without jurisdiction and mala fide.

The latest decision, dismissing the cases, simply states that military courts are duly constituted under the constitution and the law (ie the constitution as amended through the 21st Amendment and the amended Army Act), that the decisions rendered were not without jurisdiction as the convicts were tried for offences that fell within the domain of the military, and there was no mala fide in law (ie the law was not misapplied) or mala fide in fact (ie the officers acting as judges did not act in bad faith or harbour any personal bias against the convicts).

How can this decision be wronged after the 21st Amendment decision? The threshold to be met by the state to establish that a trial is fair has been set so low that the possibility of failing it is miniscule. Our traditional understanding of natural justice has been that trials are to be conducted by neutral arbiters in accordance with due process. The need for due process is highlighted by other principles of justice such as the ‘presumption of innocence till someone is proven guilty’ and the need that ‘justice is not only done but also seen to be done.’

That understanding is now history. The right not be held in secret confinement, to be confronted with charges upon arrest, to be presented before a magistrate without delay, to be defended by an attorney of choice and to be given a public trial are no longer rights in Pakistan. Due process is bereft of all its purpose. Presumption of innocence stands reversed. And the concept of neutral arbiter stands reduced to someone who holds no personal grudge against you, even if it is someone in uniform under the command of those who arrest, investigate and prosecute you.

Our state and society have collectively conceded that it is not possible to fight terror and uphold fundamental rights of citizens simultaneously without even subjecting the argument to scrutiny. We have conceded that the existing state of our security is such that we can dispense with the need for checks and balances. We have accepted that at a time when our security forces are fighting terrorists it is unpatriotic to independently verify and ensure that they commit no excesses even when they act as police, judge, jury and executioner wrapped in one.

We have stopped asking why it is impossible for security agencies to present a criminal, arrested in Karachi for example, before a magistrate within 24 hours of the arrest. We have stopped asking why it is impossible to investigate a crime thoroughly, collect evidence, document it and present it in court to seek a conviction instead of holding suspects without charging them, torturing them to get confessions and using such confessions in media trials. We have stopped asking what it will take to do things right and why we aren’t doing them.

We have become a people who have lost the ability to see things other than in black and white, to appreciate the virtue of proportionality, to understand that use of excessive force is unjust and undesirable. We support the treatment meted out to suspects in the Sri Lankan team terror attack or our Malik Ishaqs, reportedly killed in encounters while in custody of security forces, without compunction. We don’t care about citizens going missing or showing up in body bags so long as the state insinuates that they were involved with terror.

If we are convinced that some workers of the MQM are mixed up with terror we support the Rangers subjecting all MQM workers to no-holds-barred treatment. We will not stop to ask why the state is unable to control and monitor the exit and re-entry of MQM militants if and when they go to India for training. We will not stop to ask why our state is relying exclusively on the UK to punish Altaf Hussain for money laundering instead of bringing perpetrators to book in Pakistan, especially if that money is the produce of Karachi’s extortion networks.

Are we turning Pakistan into a vigilante state on the presumption that it is no longer possible to defend our interests in a justifiable manner? Are we losing our moral compass? Why can't we be opposed to terrorists and their aiders, abettors and sympathisers, and also oppose missing persons, encounters and body bags at the same time? Why can one not be opposed to Indian oppression in Kashmir and its designs and interference in Balochistan as well as our state’s misplaced policy toward LeTs, JeMs and the Afghan Taliban?

Patriotism is a good thing. But it is not a replacement for disclosure by and accountability of state institutions. If patriotism and fear of threats is used to undermine rule of law and silence the critique of misplaced state attitudes and policies, it will not strengthen but weaken Pakistan. If we have come to a pass where we can literally justify murder in the name of state security, this might be the surest sign that we are losing our sense of right and wrong.

Article 9 of our constitution states that, “no person shall be deprived of life and liberty save in accordance with law.” Through the 21st Amendment and various other laws we have lowered the legal standard to be satisfied prior to taking life to such an extent that life doesn’t seem sacred anymore.

As for liberty, there is something very rotten in a polity where citizens use their liberty to delegate powers to others for the purpose of protecting such liberty, and those vested with the delegated powers use them instead to curb that very liberty.

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

-

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame -

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus -

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’ -

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter -

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud -

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels -

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing -

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras -

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards -

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest -

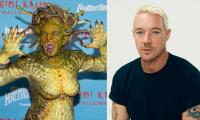

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween'

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween' -

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down -

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest?

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest? -

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights -

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed