Why Donald Trump might be the key to unlocking that damned backstop

Fumans are highly adaptable beings, capable over time of reconciling themselves to almost any condition, however miserable, and eventually thinking it tolerable.

The same is true for political ideas and systems. Remember the horror that greeted the election of Donald Trump?

But since then the great narcissist has become so familiar that he no longer seems so bad. Many past detractors have developed a kind of weird affection for the man, with growing recognition of his positives, not least a booming US economy. Judgments have changed.

With the passage of time, a similar, weary acceptance of the possibility of a no-deal Brexit has taken hold. Slowly but surely we have become anaesthetised and desensitised to the idea.

As preparations for such an outcome are ramped up – Treasury officials were told last week to work on the assumption that this is indeed where we will end up – it has taken on a momentum all of its own, such that growing numbers of people now regard it as not just inevitable but even desirable.

I’m sorry to shatter this sense of complacency, but the reality is that to hare down this route is no less reckless today than it was when the whole Brexit saga began three years ago.

Nor is it just economically reckless. For Johnson’s new administration, it is also exceptionally high risk politically.

The assembly of fresh faces, political charlatans and chancers on display at Boris’s first Cabinet meeting last week was a deeply worrying spectacle. Some of them seemed genuinely surprised to be there. They were not alone. A number of Boris’s appointments are quite plainly out of their depth.

I exclude from this judgment the new Chancellor, Sajid Javid. ? Pro-business and free market in his thinking, he has a proven grasp of finance and the needs of the UK economy, and to boot is already very familiar with the UK Treasury, its flaws as well as its strengths. But like the rest of them, he too will have signed up to the self-denying ordinance of Johnson’s no-deal bravado; hold true to the line, or you are out.

That the UK economy needs a good kick up the proverbial is not in doubt, but is the shock therapy of kissing goodbye to our automotive sector and great swathes of the rest of Britain’s manufacturing base really the correct way of going about it? I think not.

Rarely before have politics been so unpredictable, making it ever more foolish to even try. But if I were Boris, I would ignore calls for an early, pre-departure general election on a no-deal ticket. Even in the event of an electoral pact with Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party, there can be no guarantee of winning the required majority. On every level, it would be too much of a gamble.

Much safer to reach a deal. Merely putting “lipstick on the pig” plainly won’t do. Even Boris would find the required volte-face a stretch. The key here is not so much persuading the EU to shift stance as Ireland. For the EU as a whole, the backstop holds little significance.

It’s basically only there to satisfy the Irish, who in practical terms are now faced with a classic Hobson’s choice; either a softish border at some point in the future, or the certainty of a hard, economically destructive border with the UK in little more than three months’ time. In a rational world, Leo Varadkar, Ireland’s premier, would choose the former.

Donald Trump sees Brexit as an opportunity to bring Britain within the American orbit. But reconciling the Brits and the Irish? For an American president, there are few prospects more appetising, and for this consummate showman, it may be too much to resist. There may yet be a role for him to play as peacemaker. The UK trade deal can wait.

In any case, a successful Withdrawal Agreement would produce an immediate bounce in the UK economy. We’d be out, the uncertainty would lift, trade with the EU would carry on as before, and Boris could plan for a May election next year, which with Labour still cursed by a hopeless leader and the Lib Dems once more rendered irrelevant, he would almost certainly win.

For the economy, for business, and for the public finances, it could all work out rather nicely. Unfortunately, an awful lot has to go right to arrive at such a benign destination.

Top of Sajid Javid’s in tray as the new Chancellor is the now pressing decision on who to appoint as the next Governor of the Bank of England.

The relationship between Prime Minister and Chancellor is often a difficult one. David Cameron and George Osborne were unusual in seeming to act in lockstep. Friction is much more the norm, and the Governorship could be an early test.

Boris would like to give the job to his one time economic adviser as mayor of London, Gerard Lyons. Indeed, according to insiders, Lyons has already been promised it.

But there is a process to go through that is already well advanced. On the face of it, Lyons will already have failed a key test of appointability. He has no experience of running a large organisation. On the face of it he also lacks the international connections, gravitas and authority expected.

This might be thought a good thing; he’s an outsider and a believer in the opportunities of Brexit. We may need new ways of thinking. But this is a huge job, with an enormous weight of responsibility both as a linchpin in the British and global economies, and in promoting the City as an internationally pre-eminent financial centre. The other thing that counts against Lyons is that he would be seen as a political appointment. The comparison that might be made here is with Gavyn Davies, the economist Gordon Brown was keen to appoint Governor of the Bank of England. Davies would have been a good choice, but he was too close to Brown to be a credible candidate.

All this won’t necessarily stop Boris from appointing Lyons, but he will have to explain himself to Parliament, and indeed the world, if he does. Despite Lyons’ strengths as an unorthodox economist, it won’t be an easy sell.

So my money is still on either Sir Jon Cunliffe, who has already been exhaustively involved in City and international preparations for a no-deal Brexit, or Shriti Vadera, who feigns indifference but is in truth desperate for the job and would make an inspired left-of-field appointment.

She’s a woman, tick, she’s from an ethnic minority, tick, she was a key minister in the policy response to the financial crisis, tick, and she’s been a G20 facilitator, tick. —The Telegraph

-

Victoria Wood's Battle With Insecurities Exposed After Her Death

Victoria Wood's Battle With Insecurities Exposed After Her Death -

Prince Harry Lands Meghan Markle In Fresh Trouble Amid 'emotional' Distance In Marriage

Prince Harry Lands Meghan Markle In Fresh Trouble Amid 'emotional' Distance In Marriage -

Goldman Sachs’ Top Lawyer Resigns Over Epstein Connections

Goldman Sachs’ Top Lawyer Resigns Over Epstein Connections -

How Kim Kardashian Made Her Psoriasis ‘almost’ Disappear

How Kim Kardashian Made Her Psoriasis ‘almost’ Disappear -

Gemini AI: How Hackers Attempt To Extract And Replicate Model Capabilities With Prompts?

Gemini AI: How Hackers Attempt To Extract And Replicate Model Capabilities With Prompts? -

Palace Reacts To Shocking Reports Of King Charles Funding Andrew’s £12m Settlement

Palace Reacts To Shocking Reports Of King Charles Funding Andrew’s £12m Settlement -

Megan Fox 'horrified' After Ex-Machine Gun Kelly's 'risky Behavior' Comes To Light

Megan Fox 'horrified' After Ex-Machine Gun Kelly's 'risky Behavior' Comes To Light -

Prince William's True Feelings For Sarah Ferguson Exposed Amid Epstein Scandal

Prince William's True Feelings For Sarah Ferguson Exposed Amid Epstein Scandal -

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis -

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign -

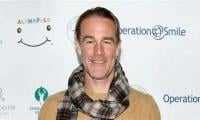

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death -

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s -

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared'

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared' -

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients -

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries -

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting