Culture Pop: Rape and power

In all the hoopla about a sitting prime minister’s disqualification there are some stories that may lie forgotten by the wayside. This is one story that shouldn’t be. Rape is not only about sex; it is ultimately about power. And when a self-proclaimed authority, such as a village council or a hastily set up family jirga, has the power to order the rape of a defenceless 16-year-old girl in full view of her family and village, then we have to look in the mirror. How exactly do family members agree to partake in this public spectacle? The whole affair is particularly preposterous in a society where any form of extra or pre-marital sex, even when consented to by both parties, is not only considered morally reprehensible but an actual crime.

The rapes were committed within an extended family. The first was surreptitious; the second was ordered, enforced and watched. According to the police report, a 12-year-old girl was raped while working in the fields just south of Multan. Following that, members of the victim’s family reportedly gathered together (by some accounts) or met the village council (by other accounts) and the brother of the first girl was afforded the opportunity to rape the sister of the accused as revenge.

“Another tribe court (panchayat) in South Punjab Multan and another girl was raped. We are still in 2002,” tweeted the activist Mukhtar Mai, who took her rapists from the same district to trial 15 years ago but later saw five of them acquitted by a superior court.

Why you may well ask was the 16-year-old girl chosen to pay for the crime her brother allegedly committed? Notwithstanding the illegality of a vigilante court apparatus, why wasn’t it the perpetrator of the crime that was tried or sentenced? Speaking to Reuters over telephone, Mai denounced the whole sordid affair. “If there were any justice in the panchayat, they should have shot the rapist. Why punish an innocent girl instead?” While one may argue with the meting out of such punishments by a kangaroo court, Mukhtar Mai’s final question must be answered. Why indeed punish someone who didn’t commit the crime?

Is it because women, especially young girls, have little to no agency or individual rights in many parts of Pakistani society? Their barter for crimes committed by male relatives is proof of their commodification as ‘property’. Women are the repositories of honour, their bodies the designated battleground for multiple familial or tribal disputes for which they are repeatedly used to settle scores. If they are not killed for ‘honour’, they are exchanged for honour.

The DSP on the case told a local newspaper that the second victim’s mother, Kaneez Mai, had offered either of her two married daughters on the condition that no legal action be taken against her son. But the panchayat demanded that she offer the youngest. If true, how chilling is it that a mother would offer her daughters to be raped in return for her son’s freedom? When honour resides in womenfolk it is only through direct damage to them that it is vindicated. Meanwhile, the perpetrators get off scot-free.

In many parts of Pakistan, women have no real decision-making power over their lives. They are sometimes sold off in marriage to much older men or, in any case, married off without their consent. The cultural practice of badla-e-sulh, vani or swara, recently highlighted in the TV drama ‘Sammi’, allows for young girls, often children, to be married into another tribe as punishment for a crime committed by a male relative. Article 310A of the Pakistan Penal Code says that compelling a woman to enter into a marriage “or otherwise” to settle criminal or civil disputes is punishable by law by imprisonment and a fine of Rs500,000.

In 2016, the Punjab Protection of Women against Violence Act criminalised most forms of violence against women – including domestic, psychological and sexual violence – instituted a hotline for reporting abuse and ordered the establishment of women’s shelters where, incidentally, the Multan rapes were reported by the mothers of the two girls. There are, however, huge gaps between law and implementation. Incursions against women occur daily. But after the initial social media outrage and the “taking notice” by the prime and chief ministers, most cases drop out of the public’s favour. Laws are passed and headlines are made, but the political will for implementation is weak.

A few weeks ago, the UN Human Rights Committee asked the Pakistani government what steps it had taken to regulate parallel ‘justice’ systems. The government fobbed off the reply, claiming it “could not exercise jurisdiction in criminal matters” and that the sole authority in that respect rested with the national courts. “Pakistan has learnt nothing from Mukhtar Mai’s gang rape,” observes Oscar-winning filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, “Had we sent her rapists to jail and made an example out of them, had we as a country resolutely condemned the rape then perhaps the two girls would have been spared.”

In actuality, rape statistics are increasing and the stigma around reporting means the figure is probably much larger. In 2016, the HRCP documented at least 2,446 cases of VAW in the country, including 958 rapes and numerous women who were stripped in public. In 2014, a report by War against Rape (WAR) estimated that of the 383 sexual assault cases reported in hospitals across Karachi, FIRs were registered only against 27.67 percent of the cases. According to the data privately collected by WAR, primarily through medical examinations in hospitals, it was estimated that at least four women were raped every day in Pakistan during 2014.

For every Mukhtar Mai and Kainat Soomro – who have both pursued justice in the courts – there are many more who are not given the support to speak up. The psychological damage done by remaining silent is toxic. The HRCP reports that almost 800 rape survivors had either attempted to take their lives or had committed suicide. On Friday the chief justice of Pakistan took suo motu notice of the Multan double rape case. And Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif reacted strongly by suspending all police officers at the local police station. However, we have all seen such theatrics before with no tangible results. Over 20 people have been arrested but the main culprits are still at large. This is not the first time a jirga has ordered a rape.

Amnesty’s Pakistan Campaigner Nadia Rahman Khan summed it up in the following words: “By allowing these councils to operate, the authorities are complicit in the crimes they order. It is not enough to arrest people after horrific attacks that take place. The authorities have a duty to protect women, prevent further such attacks, and end the fear and stigma that victims suffer”.

The writer is a journalist based in London and works with the BBC World Service as a broadcaster. Twitter: @fifiharoon

-

How Liam Payne’s Death Impacted Awareness About Mental Health

How Liam Payne’s Death Impacted Awareness About Mental Health -

Scientists Reveal How Sleeping Can Unlock Your Creative Potential

Scientists Reveal How Sleeping Can Unlock Your Creative Potential -

OpenAI CEO Calls AI Water Concerns ‘fake’

OpenAI CEO Calls AI Water Concerns ‘fake’ -

Taylor Swift Expresses How Negative Body Comments Triggered Her

Taylor Swift Expresses How Negative Body Comments Triggered Her -

Prince William Plans Bold Shake-up To Restore Public Trust Amid Andrew Drama

Prince William Plans Bold Shake-up To Restore Public Trust Amid Andrew Drama -

Apple IPhone 18 Pro Series To Launch In Bold Red Colour: Report

Apple IPhone 18 Pro Series To Launch In Bold Red Colour: Report -

Apple Developing AI Pendant Powered By In-house Visual Models

Apple Developing AI Pendant Powered By In-house Visual Models -

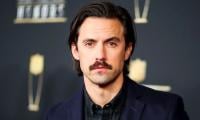

'Gilmore Girls' Milo Ventimiglia Shares How He Would React If His Daughter Ke'ala Coral Chose 'team Dean'

'Gilmore Girls' Milo Ventimiglia Shares How He Would React If His Daughter Ke'ala Coral Chose 'team Dean' -

New AGI Benchmark: Demis Hassabis Proposes ‘Einstein Test’—Ultimate Challenge To Prove True Intelligence

New AGI Benchmark: Demis Hassabis Proposes ‘Einstein Test’—Ultimate Challenge To Prove True Intelligence -

NASA Artemis 2 Moon Mission Faces Unexpected Delay Ahead Of March Launch

NASA Artemis 2 Moon Mission Faces Unexpected Delay Ahead Of March Launch -

Kate Middleton Reclaims Spotlight With Confidence Amid Andrew Drama

Kate Middleton Reclaims Spotlight With Confidence Amid Andrew Drama -

Lady Gaga Details How Eating Disorder Affected Her Career: 'I Had To Stop'

Lady Gaga Details How Eating Disorder Affected Her Career: 'I Had To Stop' -

Why Elon Musk Believes Guardrails Or Kill Switches Won’t Save Humanity From AI Risks

Why Elon Musk Believes Guardrails Or Kill Switches Won’t Save Humanity From AI Risks -

'Devastated' Richard E. Grant Details How A Friend Of Thirty Years Betrayed Him: 'Such Toxicity'

'Devastated' Richard E. Grant Details How A Friend Of Thirty Years Betrayed Him: 'Such Toxicity' -

Rider Strong Finally Unveils Why He Opposed The Idea Of Matthew Lawrence’s Inclusion In 'Boy Meets World'

Rider Strong Finally Unveils Why He Opposed The Idea Of Matthew Lawrence’s Inclusion In 'Boy Meets World' -

Who Was ‘El Mencho’? Inside The Rise And Fall Of Mexico’s Most Wanted Drug Lord Killed In Military Operation

Who Was ‘El Mencho’? Inside The Rise And Fall Of Mexico’s Most Wanted Drug Lord Killed In Military Operation