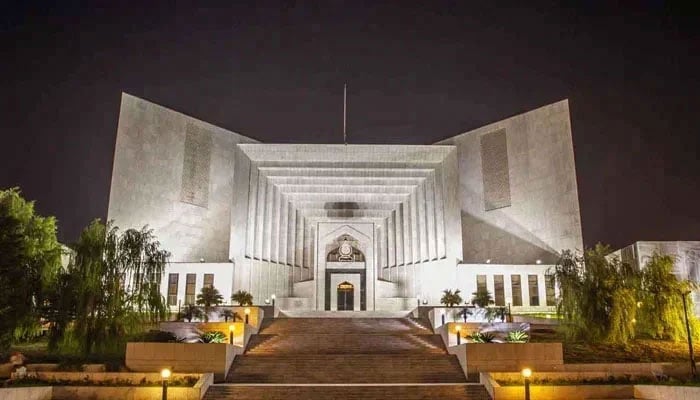

Transfer of judges to IHC constitutional, rules SC

Transfer of judge by president by means of Article 200 cannot be construed as fresh appointment

ISLAMABAD: The Supreme Court on Thursday dismissed identical petitions challenging the transfer of judges from various high courts to the Islamabad High Court (IHC), ruling that the President of Pakistan’s transfer notification falls within the constitutional framework and cannot be declared ultra vires.

A five-member Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court, headed by Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar, announced judgement in the identical petitions filed by five IHC judges against transfers as well as seniority issue of the judges. Other members of the bench included Justice Naeem Akhter Afghan, Justice Shahid Bilal Hassan, Justice Salahuddin Panhwar and Justice Shakeel Ahmad.

The court by majority of 3 to 2, comprising Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar, Justice Shahid Bilal Hassan and Justice Salahuddin Panhwar, dismissed the identical petitions after holding that the transfer of judges by the president by means of the impugned notification is within the framework of the Constitution and cannot be declared ultra vires. Whereas, Justice Naeem Akhter Afghan and Justice Shakeel Ahmad, vide their own short order, allowed the petitions and set aside the notification No.F.10(2)/2024-A.II, dated 01.02 2025.

The majority judges, however, partially remanded the matter to the president, without upsetting the notification of transfer, to determine the seniority after examining/ vetting the service record of the transferred judges as soon as possible, including the question of whether the transfer is on a permanent or temporary basis.

“Till such time that the seniority and nature of transfer (permanent or temporary) of the transferee judges is determined by the President of Pakistan by means of notification/ order, Justice Sardar Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar, already holding the office of Acting Chief Justice of the Islamabad High Court, will continue to perform as the Acting Chief Justice of the Islamabad High Court,” said the short order.

The court noted that president’s powers under sub-article (1) of Article 200 of the Constitution for the transfer of a judge of the high court from one high court to another, and the provisions contained under Article 175A for appointment of judges to the Supreme Court, high courts and the Federal Shariat Court by the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP) are two distinct provisions dealing with different situations and niceties.

The court held that neither do they overlap nor override each other, adding that the transfer of a judge by the president by means of Article 200 (permanently or temporarily) cannot be construed as a fresh appointment.

Furthermore, the court held that the powers of transfer conferred to the president by none other than the framers of the Constitution cannot be questioned on the anvil or ground that if the posts were vacant in the IHC, then why they were not filled up by the JCP through fresh appointments. “One more important fact that cannot be lost sight of is that the transfer from one high court to another high court can only be made within the sanctioned strength, which can only be regarded as a mere transfer and does not amount to raising the sanctioned strength of a particular high court,” the short order held.

In all fairness, the court observed, presuming all judicial posts must be filled exclusively by the JCP through fresh appointments would not only contravene the framers’ clear constitutional intent but also undermine the very foundation of Article 200. This provision operates independently—neither subordinate to nor contingent upon Article 175A—and serves as a standalone constitutional mechanism for the transfer of high court judges, whether permanent or temporary. By contrast, the exclusive authority to appoint judges rests incontrovertibly with the JCP under Article 175A, a distinction that safeguards the autonomy of both processes.

As far as Section 3 of the Islamabad High Court Act, 2010, is concerned, the court held, it only divulges that the IHC shall consist of a chief justice and 12 other judges to be appointed from the provinces and other territories of Pakistan in accordance with the Constitution.

“In our considered view, this provision is only germane to the appointment of judges and does not, in any way, mean that a judge can only join the Islamabad High Court through a fresh appointment and not by way of a transfer or, in other words, that Article 200 does not apply to the Islamabad High Court, which interpretation would be against the exactitudes of the Constitution,” the short order said.

The court held that neither can Section 3 of the Act supersede/ override a constitutional mandate, nor can it control, nullify, or rescind the powers of transfer that are vested in the president under Article 200.

“Nevertheless, the exercise of the powers of transfer by the President of Pakistan under Article 200 of the Constitution is not unregulated or unfettered,” said the order, adding that it is structured on a four tier formula which expounds that no judge shall be transferred except with his consent and after consultation by the president with the Chief Justice of Pakistan and the chief justices of both high courts. “What does this mean? If at the very initial stage, a judge intended to be transferred from one high court to another high court refuses the offer/ proposal, then obviously the matter ends forthwith,” it noted.

Even in the case of consent, the court held, the transfer shall be subject to consultation with two chief justices of the high courts and the Chief Justice of Pakistan, as the paterfamilias of judiciary, who may, during the consultation process, pragmatically ruminate the pros and cons germane to the transfer proposal, including the aspect of public interest, if any.

“Hence, for all intents and purposes, it is reverberated beyond any shadow of doubt that before exercising the power of transfer, certain inbuilt procedures and mechanisms have to be followed in letter and spirit and the decision, or the right of refusal or primacy, is within the sphere and realm of judiciary and not within the domain of executives,” the court held

The short order further held that it does not in any case compromise the independence of the judiciary for the discernable reason that the decision to accept or reject is exclusively within the hands of the judiciary. “Thus, for all intents and purposes, the transfer of judges by the President of Pakistan, by means of the impugned Notification dated 1st February 2025 is within the framework of the Constitution and cannot be declared ultra vires,” the order declared.

“We are sanguine that in normal circumstances, the decision on inter se seniority disputes or disagreements amongst the judges of a high court are within the domain of the chief justice of that high court, at the administrative side, but here the matter relates to the transfer of judges from other high courts to the Islamabad High Court,” it maintained. Thus, the court held, the seniority issue is not exactly inter se seniority within the existing strength of judges of one and the same high court, prior to bringing forth the transfer of three judges under Article 200, but is somewhat cropped up between the transferee judges and the judges that already existed prior to the transfer.

The court noted that there is no All Pakistan Cadre/ unified or combined seniority list of high court judges for determining their seniority at the time of transfer. “Therefore, in our view, the terms and conditions of transfer (permanently or temporary) including seniority should have been taken up and mentioned by the president at the time of issuing the notification of transfer in terms of Article 200 of the Constitution,” the judgement concluded.

Meanwhile, in their dissenting judgement, Justice Naeem Akhtar Afghan and Justice Shakeel Ahmed, after accepting the petitions, declared the transfer of LHC judge Justice Sardar Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar, SHC judge Justice Khadim Hussain Soomro, and BHC additional judge Justice Muhammad Asif to the IHC by the president as null, void and of no legal effect.

Both the judges held that the permanent transfer of three judges to IHC has been made by the president in wrong exercise of discretion under Clause (1) of Article 200, adding that it has offended Article 175A of the Constitution and has made the same redundant. The two judges held that Clause (2) of Article 200 is subservient to Clause (1) of Article 200, and both are interconnected. Similarly, they noted that the process for permanent transfer of three judges to the IHC is suffering from concealment of relevant and material facts from the transferee judges, from the chief justices of IHC, LHC, SHC, BHC and from the Chief Justice of Pakistan.

Justice Afghan and Justice Shakeel noted that the process for permanent transfer of three judges to IHC is also lacking meaningful, purposive and consensus oriented consultation with the chief justices of IHC, LHC, SHC, BHC and CJP on all the relevant issues. Similarly, they held that the process for permanent transfer of three judges to IHC has been completed in an unnecessary haste, adding that it is suffering from mala fide in facts as well as mala fide in law. Likewise, they held that it has not been made by the president in the public interest.

They also noted that counsel for the petitioners contended that the six sitting IHC judges wrote letter dated 25th of March, 2024 to the then CJP/ JCP chairman, senior puisne judge, Supreme Court of Pakistan/ Member JCP and three other members of JCP with complaints of interference in judicial functions and/ or intimidation of judges of the IHC by the intelligence agencies; the issue was taken up in full court meeting of the Supreme Court as well as on the judicial side and it had triggered the process for transfer of three judges to the IHC from the LHC, SHC and BHC.

The two judges, however, held that the contention raised by counsel for the petitioners cannot be believed as the intelligence agencies have no role under the Constitution for appointment or transfer of judges. Being subordinate to the Executive, the two judges held, the intelligence agencies cannot override the Executive, the judiciary, the constitutional bodies and the constitutional office holders.

Earlier, the court had reserved the judgment after Idress Ashraf, counsel for PTI founding Chairman Imran Khan and Attorney General Mansoor Usman Awan concluded their arguments in rebuttal.

Meanwhile, two back-to-back meetings of the JCP were held in the Supreme Court’s conference room under the chairmanship of Chief Justice of Pakistan Yahya Afridi.

The forum extended the tenure of Justice Aminuddin Khan for another six months as head of the Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court (SC), while also approving a similar extension for the SHC constitutional benches.

The commission, by a majority of its members, approved the extension of the SC Constitutional Bench till November 30, 2025.

The commission also constituted a broad-based committee comprising members of the judiciary, parliament, executive and legal community. The committee will draft rules for annual judicial performance evaluations of high court judges. In the second JCP meeting, held at 2:30 pm, the commission extended the tenure of the constitutional benches of the Sindh High Court for six months starting July 23, 2025. As part of this restructuring, Justice Adnan Iqbal Chaudhry was appointed to replace Justice Agha Faisal, while Justice Jaffer Raza replaced Justice Sana Akram Minhas.

-

EU Leaders Divided Over ‘Buy European’ Push At Belgium Summit: How Will It Shape Europe's Volatile Economy?

EU Leaders Divided Over ‘Buy European’ Push At Belgium Summit: How Will It Shape Europe's Volatile Economy? -

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle Issue A Statement Two Days After King Charles

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle Issue A Statement Two Days After King Charles -

'The Masked Singer' Pays Homage To James Van Der Beek After His Death

'The Masked Singer' Pays Homage To James Van Der Beek After His Death -

Elon Musk’s XAI Shake-up Amid Co-founders’ Departure: What’s Next For AI Venture?

Elon Musk’s XAI Shake-up Amid Co-founders’ Departure: What’s Next For AI Venture? -

Prince William, King Charles Are Becoming Accessories To Andrew’s Crimes? Expert Explains Legality

Prince William, King Charles Are Becoming Accessories To Andrew’s Crimes? Expert Explains Legality -

Seedance 2.0: How It Redefines The Future Of AI Sector

Seedance 2.0: How It Redefines The Future Of AI Sector -

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor Still Has A Loan To Pay Back: Heres Everything To Know

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor Still Has A Loan To Pay Back: Heres Everything To Know -

US House Passes ‘SAVE America Act’: Key Benefits, Risks & Voter Impact Explained

US House Passes ‘SAVE America Act’: Key Benefits, Risks & Voter Impact Explained -

'Heartbroken' Busy Philipps Mourns Death Of Her Friend James Van Der Beek

'Heartbroken' Busy Philipps Mourns Death Of Her Friend James Van Der Beek -

Gwyneth Paltrow Discusses ‘bizarre’ Ways Of Dealing With Chronic Illness

Gwyneth Paltrow Discusses ‘bizarre’ Ways Of Dealing With Chronic Illness -

US House Passes Resolution To Rescind Trump’s Tariffs On Canada

US House Passes Resolution To Rescind Trump’s Tariffs On Canada -

Reese Witherspoon Pays Tribute To James Van Der Beek After His Death

Reese Witherspoon Pays Tribute To James Van Der Beek After His Death -

Halsey Explains ‘bittersweet’ Endometriosis Diagnosis

Halsey Explains ‘bittersweet’ Endometriosis Diagnosis -

'Single' Zayn Malik Shares Whether He Wants More Kids

'Single' Zayn Malik Shares Whether He Wants More Kids -

James Van Der Beek’s Family Faces Crisis After His Death

James Van Der Beek’s Family Faces Crisis After His Death -

Courteney Cox Celebrates Jennifer Aniston’s 57th Birthday With ‘Friends’ Throwback

Courteney Cox Celebrates Jennifer Aniston’s 57th Birthday With ‘Friends’ Throwback