Beyond textiles: Rethinking Pakistan’s place in global trade

LAHORE: Although the world anticipated some tariff measures from Trump, most assumed these would target America’s major trading partners. The inclusion of smaller economies such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka came as a surprise.

While larger trading partners are preparing countermeasures in the form of reciprocal tariffs, smaller nations like Pakistan lack such leverage. Some experts suggest that Pakistan could consider lowering duties on US imports in exchange for tariff concessions from Washington. However, this is easier said than done. Under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, Pakistan cannot unilaterally offer reduced tariffs to the US without a formal bilateral agreement -- something the US is in no rush to negotiate. Any unilateral tariff reduction would automatically extend to all WTO members.

Pakistan must develop a strategic roadmap with practical and realistic steps to reshape its export strategy and strengthen its position in future trade negotiations. A major weakness lies in its over-reliance on textile exports, low-tech products, and raw agricultural commodities. There is an urgent need to diversify export offerings.

Strategic actions in this regard should include a transition from cotton yarn to value-added products such as ready-made garments, denim brands and technical textiles. Similarly, rather than exporting raw agricultural goods, Pakistan should focus on processing them prior to export. Packaged halal foods, frozen meals, juices and spices (value-added agri-exports) offer significant export potential.

Pakistan also has a growing IT sector that remains underutilised. The government must support software exports and call centre development, drawing lessons from countries like India and the Philippines. The country has developed light engineering capabilities, and greater efforts should be made to expand exports of auto parts, electric fans, medical instruments and electrical fittings.

Currently, Pakistan’s exports are overly concentrated in a few markets -- namely the US, UK, and UAE -- which leaves them vulnerable to shifting political dynamics and tariff regimes. There is increasing demand and lower competition in African markets, where the state could promote trade through barter arrangements or trade finance mechanisms. For Central Asia, Pakistan should capitalise on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its strategic location. In ASEAN countries, it must explore opportunities for rice, processed foods and cotton-based goods. With China, Pakistan should leverage its Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to increase exports of rice, seafood, halal meat and bulk materials.

To realise these goals, Pakistan must improve its export competitiveness. High logistics costs, unreliable power supply and bureaucratic red tape are damaging export pricing. Reforms are needed in the energy sector, as well as investments in dry ports, warehousing, trucking and customs processes. Cutting documentation hurdles and customs delays is essential.

The government should provide matching grants for export marketing, upgraded packaging and design innovation. It should also establish product development centres (PDCs) for key sectors like textiles, leather goods and surgical instruments. Pakistan is often perceived as a low-end supplier with minimal brand recognition. Investing in a ‘Made in Pakistan’ brand -- highlighting eco-friendly, Islamic fashion and halal certification -- could reshape this image.

Weak economic diplomacy, reactive policy approaches and poor coordination between the commerce ministry, embassies and business organisations also hinder export growth. There is a pressing need to train commercial attaches in export intelligence and business matchmaking. Business chambers must be involved in trade negotiations to ensure on-ground realities are considered. Building regional coalitions with countries like Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Kenya could also strengthen lobbying efforts against discriminatory tariffs.

Now is also the time to empower freelancers and IT startups by simplifying international payment systems and offering clarity on taxation. Education exports should be promoted by attracting students from Africa and Central Asia. Meanwhile, Pakistan could generate much-needed foreign exchange by promoting medical tourism through hospitals in Lahore and Karachi, particularly for specialised surgeries offered at competitive prices. Enhancing the capacity of the EXIM Bank to provide competitive export credit and offering interest rate subsidies on working capital for high-potential exporters would also support export growth.

In the long term, Pakistan should aim to raise its exports-to-GDP ratio from the current 10 per cent to 20 per cent within a decade. The goal should be to bring one million SMEs into the formal export economy and achieve $50 billion in non-textile exports by 2035 -- up from the current level of less than $10 billion. Pakistan must fully utilise its geo-strategic location to become a regional manufacturing and trade hub.

-

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis -

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign -

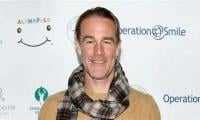

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death -

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s -

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared'

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared' -

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients -

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries -

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting -

China Debuts World’s First AI-powered Earth Observation Satellite For Smart Cities

China Debuts World’s First AI-powered Earth Observation Satellite For Smart Cities -

Royal Family Desperate To Push Andrew As Far Away As Possible: Expert

Royal Family Desperate To Push Andrew As Far Away As Possible: Expert -

Cruz Beckham Releases New Romantic Track 'For Your Love'

Cruz Beckham Releases New Romantic Track 'For Your Love' -

5 Celebrities You Didn't Know Have Experienced Depression

5 Celebrities You Didn't Know Have Experienced Depression -

Trump Considers Scaling Back Trade Levies On Steel, Aluminium In Response To Rising Costs

Trump Considers Scaling Back Trade Levies On Steel, Aluminium In Response To Rising Costs -

Claude AI Shutdown Simulation Sparks Fresh AI Safety Concerns

Claude AI Shutdown Simulation Sparks Fresh AI Safety Concerns -

King Charles Vows Not To Let Andrew Scandal Overshadow His Special Project

King Charles Vows Not To Let Andrew Scandal Overshadow His Special Project -

Spotify Says Its Best Engineers No Longer Write Code As AI Takes Over

Spotify Says Its Best Engineers No Longer Write Code As AI Takes Over