Physicians, heal thyself

Part - IAs expected, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Medical Teaching Institutions Reforms Act 2015 has generated resistance from various vested interests. This was to be expected. The legislation proposes changes in the way government hospitals are run, with the formation of a board of governors (BoG) for each Medical Teaching Institute

By our correspondents

July 16, 2015

Part - I

As expected, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Medical Teaching Institutions Reforms Act 2015 has generated resistance from various vested interests. This was to be expected. The legislation proposes changes in the way government hospitals are run, with the formation of a board of governors (BoG) for each Medical Teaching Institute (MTI). It also seeks to ask the senior physicians to choose between being civil servants or to employees of the institute itself.

The existing ‘civil servants’ and ‘employees of the MTI’ are given the option of either doing institution-based private practice (IBP) or outside private medical practices. Future employees, however, will only have the option of IBP. While the legislation is not ideal, it definitely is a step in the right direction. The implementation will now, however, test the resolve on the part of the political leadership of the province.

In this article I write to explain what the reality of the health care system is and address some of these issues in context of Pakhtunkhwa. I look at the problems afflicting the medical care, administration & teaching at the Medical Teaching Institutions in Pakhtunkhwa in particular and make some recommendations.

The present system in our tertiary care hospitals is broken. In fact, there is no system at all. What we have is a hodgepodge of arbitrary rules and regulations resulting from ignorance on the part of the government and bureaucracy and convenience of the physicians and ancillary staff with almost total disregard for efficiency and patient care.

This system was adopted from the old English and German systems of the 19th & early 20th centuries. It has since long become redundant in most of the developed world, even in India – as well as in quality private hospitals within Pakistan.

The present system in our tertiary care hospitals could aptly be termed ‘professor-centric’ rather than ‘patient-centric’. The universe of the hospitals is centred around the professors. The head of the unit is considered the god of everything within his ‘unit’ – with little or no accountability at all. A particular ‘unit’ or ‘ward’ is, for all practical purposes, the personal fiefdom of the professor. As one junior doctor remarked, the only thing lacking is separate flags or coat of arms.

There is a terrible waste of human resources within this system. There are four post-graduate qualified consultants within one unit: the professor, the associate professor, the assistant professor and the senior registrar. Instead of delivering independent patient care, the latter three, equally qualified by all means, work under the supervision of the professor who also presides over 20-30 trainee medical officers (TMOs) and some 10-20 house officers (HOs).

There is no bed-management system in place. Let us take the example of a typical medical unit. It has about 45 patient beds. It takes turns with on-call or emergency days. This creates a situation where if ‘Medical A’ is on-call, the 45 beds fill in very quickly. Now extra beds, in some cases brought by the attendants of the patients, are arranged even in the corridors to accommodate new admissions. This places more burden on resources such as toilets, ventilation, air-conditioning etc and creates an unsafe atmosphere for patient care. When even these ‘special beds’ get filled, new intake is refused citing bed unavailability.

At the same time however, the units that are not on-call, will have a number of beds available but no patients can be accommodated there as they are the domain of other professors. A survey conducted at the Khyber Teaching Hospital in Peshawar in the recent past revealed that the overall bed occupancy rate was only about 70 percent at any given time. This means that in a 1000-bed hospital, approximately 300 beds are empty while many deserving and critically ill patients are refused admission on account of this artificial bed ‘shortage’.

It is a rather unique phenomenon that there have to be strictly dedicated units or ‘beds’ for allied specialties such as endocrinology, nephrology, gastroenterology, ophthalmology and ENT etc. This again is because of the false but convenient notion that to employee a consultant (a professor), he or she has to head a physical space. This is one of the hindrances in the way of hiring more manpower, including many desperately needed sub-specialties.

The public, for example, may be surprised to know that none of our so-called tertiary care hospitals have any properly trained infectious disease specialists who can deal with conditions like complicated tuberculosis and other complex infections.

This corrupt and outdated system prevents efficiency and has developed a remarkable illusion of being overburdened. True that there are other variables as well but the hospitals will be overburdened if an efficient mechanism for patient care is not in place. The on-call unit will certainly look busy when it has patients lying in the corridors while in reality the next-door unit has 20 beds lying empty.

Working hours at our hospitals must be the most lenient anywhere in the world. The official hours are from 8:00am to 2:30pm but even these are not adhered to. A typical day for most professors at hospitals dawns at around 10:00am and ends at noon. During these two hours, patient care and teaching responsibilities are somehow miraculously handled. In some of the units, the professor and the associate or assistant professor have a mutual understanding where one would not show up at all for a week or so and then it is the other’s turn to take this unofficial vacation.

The OPD or outpatient clinics are the most neglected. Their hours of working are dismal. Most units start their OPD at around 10:00am and close shop by noon or at most 1:00pm. How can you then not get a mad rush at the OPD, when the patients are to be crammed within this two or three-hour window? Even with these abysmal hours, the senior staff seldom shows up at the OPD themselves. I was told that a certain professor of ophthalmology at one of the Peshawar hospitals has not graced the OPD with his presence for the last four or so years. This certainly is not unique.

The Operation Theatre (OT) also schedules cases from 7 or 8:00am to only noon or 1:00pm. Most of the staff then calls it a day with only skeleton staff left to deal with emergencies. We hear time and again that the OT is overburdened. Well it may not be overburdened anymore and two patients might not need to be operated upon in the same room at the same time – violating all codes of privacy and ethics – if the OT would schedule cases every working day from 7:00 am to 5:00 pm.

To be continued

The writer is former president of the Association of Pakistani Cardiologists of North America (APCNA).

As expected, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Medical Teaching Institutions Reforms Act 2015 has generated resistance from various vested interests. This was to be expected. The legislation proposes changes in the way government hospitals are run, with the formation of a board of governors (BoG) for each Medical Teaching Institute (MTI). It also seeks to ask the senior physicians to choose between being civil servants or to employees of the institute itself.

The existing ‘civil servants’ and ‘employees of the MTI’ are given the option of either doing institution-based private practice (IBP) or outside private medical practices. Future employees, however, will only have the option of IBP. While the legislation is not ideal, it definitely is a step in the right direction. The implementation will now, however, test the resolve on the part of the political leadership of the province.

In this article I write to explain what the reality of the health care system is and address some of these issues in context of Pakhtunkhwa. I look at the problems afflicting the medical care, administration & teaching at the Medical Teaching Institutions in Pakhtunkhwa in particular and make some recommendations.

The present system in our tertiary care hospitals is broken. In fact, there is no system at all. What we have is a hodgepodge of arbitrary rules and regulations resulting from ignorance on the part of the government and bureaucracy and convenience of the physicians and ancillary staff with almost total disregard for efficiency and patient care.

This system was adopted from the old English and German systems of the 19th & early 20th centuries. It has since long become redundant in most of the developed world, even in India – as well as in quality private hospitals within Pakistan.

The present system in our tertiary care hospitals could aptly be termed ‘professor-centric’ rather than ‘patient-centric’. The universe of the hospitals is centred around the professors. The head of the unit is considered the god of everything within his ‘unit’ – with little or no accountability at all. A particular ‘unit’ or ‘ward’ is, for all practical purposes, the personal fiefdom of the professor. As one junior doctor remarked, the only thing lacking is separate flags or coat of arms.

There is a terrible waste of human resources within this system. There are four post-graduate qualified consultants within one unit: the professor, the associate professor, the assistant professor and the senior registrar. Instead of delivering independent patient care, the latter three, equally qualified by all means, work under the supervision of the professor who also presides over 20-30 trainee medical officers (TMOs) and some 10-20 house officers (HOs).

There is no bed-management system in place. Let us take the example of a typical medical unit. It has about 45 patient beds. It takes turns with on-call or emergency days. This creates a situation where if ‘Medical A’ is on-call, the 45 beds fill in very quickly. Now extra beds, in some cases brought by the attendants of the patients, are arranged even in the corridors to accommodate new admissions. This places more burden on resources such as toilets, ventilation, air-conditioning etc and creates an unsafe atmosphere for patient care. When even these ‘special beds’ get filled, new intake is refused citing bed unavailability.

At the same time however, the units that are not on-call, will have a number of beds available but no patients can be accommodated there as they are the domain of other professors. A survey conducted at the Khyber Teaching Hospital in Peshawar in the recent past revealed that the overall bed occupancy rate was only about 70 percent at any given time. This means that in a 1000-bed hospital, approximately 300 beds are empty while many deserving and critically ill patients are refused admission on account of this artificial bed ‘shortage’.

It is a rather unique phenomenon that there have to be strictly dedicated units or ‘beds’ for allied specialties such as endocrinology, nephrology, gastroenterology, ophthalmology and ENT etc. This again is because of the false but convenient notion that to employee a consultant (a professor), he or she has to head a physical space. This is one of the hindrances in the way of hiring more manpower, including many desperately needed sub-specialties.

The public, for example, may be surprised to know that none of our so-called tertiary care hospitals have any properly trained infectious disease specialists who can deal with conditions like complicated tuberculosis and other complex infections.

This corrupt and outdated system prevents efficiency and has developed a remarkable illusion of being overburdened. True that there are other variables as well but the hospitals will be overburdened if an efficient mechanism for patient care is not in place. The on-call unit will certainly look busy when it has patients lying in the corridors while in reality the next-door unit has 20 beds lying empty.

Working hours at our hospitals must be the most lenient anywhere in the world. The official hours are from 8:00am to 2:30pm but even these are not adhered to. A typical day for most professors at hospitals dawns at around 10:00am and ends at noon. During these two hours, patient care and teaching responsibilities are somehow miraculously handled. In some of the units, the professor and the associate or assistant professor have a mutual understanding where one would not show up at all for a week or so and then it is the other’s turn to take this unofficial vacation.

The OPD or outpatient clinics are the most neglected. Their hours of working are dismal. Most units start their OPD at around 10:00am and close shop by noon or at most 1:00pm. How can you then not get a mad rush at the OPD, when the patients are to be crammed within this two or three-hour window? Even with these abysmal hours, the senior staff seldom shows up at the OPD themselves. I was told that a certain professor of ophthalmology at one of the Peshawar hospitals has not graced the OPD with his presence for the last four or so years. This certainly is not unique.

The Operation Theatre (OT) also schedules cases from 7 or 8:00am to only noon or 1:00pm. Most of the staff then calls it a day with only skeleton staff left to deal with emergencies. We hear time and again that the OT is overburdened. Well it may not be overburdened anymore and two patients might not need to be operated upon in the same room at the same time – violating all codes of privacy and ethics – if the OT would schedule cases every working day from 7:00 am to 5:00 pm.

To be continued

The writer is former president of the Association of Pakistani Cardiologists of North America (APCNA).

-

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis -

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign -

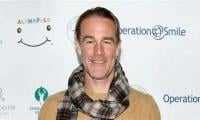

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death -

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s -

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared'

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared' -

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients -

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries -

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting -

China Debuts World’s First AI-powered Earth Observation Satellite For Smart Cities

China Debuts World’s First AI-powered Earth Observation Satellite For Smart Cities -

Royal Family Desperate To Push Andrew As Far Away As Possible: Expert

Royal Family Desperate To Push Andrew As Far Away As Possible: Expert -

Cruz Beckham Releases New Romantic Track 'For Your Love'

Cruz Beckham Releases New Romantic Track 'For Your Love' -

5 Celebrities You Didn't Know Have Experienced Depression

5 Celebrities You Didn't Know Have Experienced Depression -

Trump Considers Scaling Back Trade Levies On Steel, Aluminium In Response To Rising Costs

Trump Considers Scaling Back Trade Levies On Steel, Aluminium In Response To Rising Costs -

Claude AI Shutdown Simulation Sparks Fresh AI Safety Concerns

Claude AI Shutdown Simulation Sparks Fresh AI Safety Concerns -

King Charles Vows Not To Let Andrew Scandal Overshadow His Special Project

King Charles Vows Not To Let Andrew Scandal Overshadow His Special Project -

Spotify Says Its Best Engineers No Longer Write Code As AI Takes Over

Spotify Says Its Best Engineers No Longer Write Code As AI Takes Over