The risk of demonising Zardari

It is not difficult to understand why there is a thick tension in the air as Pakistan prepares for a

By Mosharraf Zaidi

August 26, 2008

It is not difficult to understand why there is a thick tension in the air as Pakistan prepares for a Zardari presidency. For two decades now Asif Ali Zardari has been the object of establishment, middle class and educated elite contempt. Just because the educated liberals and urban conservatives in Pakistan don't like Mr Zardari, doesn't mean he shouldn't be president. Pakistanis have a habit of personifying national failure in the shape of individuals. It is time to ditch old habits, and embrace democracy.

Within the tradition of personifying national failure, General Ziaul Haq is perhaps the favourite of the English-language babus. It is amazing how Zia single handedly created religious fanaticism, turned the country into Ronald Reagan's hand-maiden and gave rise to all the evil that lurks in Tora Bora and straddles the Durand Line. If Zia is at the top of the list, Zulfi Bhutto is a not too distant second. The most recent addition to the arsenal of both liberals and conservatives is of course the recently retired and resigned Pervez Musharraf. In many ways he trumps both Bhutto and Zia in villainous magnitude – combining the supposed institutional appetite for fanaticism, with his personal appetite for the finer things in life. Now, the knives are sharpening and September 6 is almost upon us. If and when Mr Zardari finally does take office, many Pakistanis will cringe, and weep and turn off the television in disgust.

Before Mr Zardari is tagged with the label of national villain however, it would be useful for Pakistanis to take a long, hard look at where the country is today, and how it got here. The nervous ticks that a Zardari presidency is inspiring are rooted in three issues. First, presidential power to dissolve the assemblies, second, Mr Zardari's alleged corruption, and third, the symbolism of Mr Zardari as a non-traditional political figure, occupying the Aiwan-e-Sadr. Examining these in further detail reveals little to justify any logically consistent argument against a Zardari presidency.

The issue of the potential role of the president of Pakistan as a destabilising force that can dissolve assemblies is a legitimate fear. How that is Mr Zardari's fault however, is a mystery. Before being deposed, Nawaz Sharif had successfully restored the presidency to its figurehead role, without executive powers over parliament. That restoration had been over a decade in the making, given the horrible mutilation of institutions that occurred during General Zia's era. The presidency was not a powerful position in Pakistan again until December 2003, when the 17th Amendment was passed, restoring the lost lustre of dictatorship back to the presidency. Who gave the presidency these powers? It couldn't have been Mr Zardari himself, given that he was locked up in jail at the time. In fact, it was the parliament at the time, a parliament that was loaded with two parties of note, the so-called PML – Q and the right-coalition of the MMA. Simply put, any trepidation about the powers of the presidency has nothing to do with Mr Zardari. The credit or blame for any anxiety caused by the president's powers can be placed squarely at the feet of those two parties, and their task master at the time, the former president himself. At least on the count of draconian presidential powers then, we can be certain that Mr Asif Ali Zardari is not the one who enabled a presidency that has the power to interrupt the democratic process and facilitate dictatorship.

The second issue of concern in a Zardari presidency is of course the issue of his alleged corruption. This is not a complex issue at all. From a technical, legal standpoint Mr Zardari is innocent until proven guilty. At least three different governments over a span of almost twenty years have spent millions of dollars pursuing the cases against him. They have failed to deliver a guilty verdict. It is not Mr Zardari's fault that the system of justice in Pakistan is broken, and that the prosecutors of the agenda of accountability are incompetent. This is an issue on which clarity is of vital national importance. The simple perception of wrong doing is not good enough to prosecute someone. This is a principle upon which the national outrage over Dr Aafia Siddiqui's incarceration and extradition is based. It is also the principal upon which the legitimate Chief Justice, Mr Iftikhar Chaudhry based his observations about missing persons. Pakistanis need to be consistent. If Dr Afia and a generation of bearded Pakistanis are innocent until proven guilty, then so is Mr Asif Ali Zardari. Moreover, it is hard to take the entire anti-corruption, transparency and accountability agenda seriously, when those that are responsible for delivering transparency and accountability have sullied reputations themselves. No matter who the next president is, sooner or later, the government will reinitiate the accountability agenda. The country has tried this little game several times. First was the Ehtesaab Bureau under the leadership of Saifur Rehman -- himself a target of allegations of corruption. Then it was the National Accountability Bureau -- which practiced selective morality on the issue of corruption, indemnifying some categories of the corrupt and not others. Finally of course, it was General Musharraf that signed the NRO, not Mr Zardari. In a country where the moral boundaries are so widely and liberally defined, how can one man be held accountable for unproven sins, while everyone else is allowed fiscal impunity?

Finally, there is the issue of perception, the question of what a Zardari presidency would symbolise. Perception is a funny thing, because it is driven by our own biases and our own psychoses. What did a president in uniform symbolise? Where was middle class disgust and outrage when Ayub, Zia or Musharraf took over? What did a president who had no achievements of substance to his record other than to steadily and stealthily climb the ladders of power over a forty-year career represent? Where were the bureaucratic babus and their outrage when Ghulam Ishaq Khan not only became president, but proceeded to dissolve the assemblies not once, or twice, but three times? Where was English-language elite outrage or conservative self-righteous outrage when career sycophants like Wasim Sajjad, and Rafiq Tarrar became president? Or when a banker who was plucked from nowhere to not only become chairman of the Senate, governor of Sindh, but also caretaker prime minister, and then seamlessly back to chairman of the Senate? Where is the outrage at the conflict of interest that was invariably a part of Mohammedmian Soomro's back and forths between top positions in the government – without ever being elected to any office, by any citizen of Pakistan? In each case of course, there was always a smattering of boos, and some discomfort, but nothing like the wide-scale self-pity that Pakistanis are about to dive into.

One needn't be Rehman Malik, Salman Taseer or Hussain Haqqani to recognise and acknowledge one simple fact. A democratically elected, parliamentary powerful party has the right to elect a president of its choosing. No matter how much Mr Zardari is disliked by both liberal and conservative Pakistanis, his candidature is no worse than any of the other presidents Pakistan has had over the last two decades. At least in Mr Zardari's case, there is an element of democratic redemption that perhaps among his predecessors, only Rafiq Tarrar possessed.

The truth is that Pakistan's institutions are constantly being bludgeoned by the self-righteousness of the urban educated. It is they who provide the military with the legitimacy that allows well-meaning but illegitimate dictatorships to take root. Pakistan can begin its latest journey in democratic discovery the same way in which all previous journeys have begun. By stacking the deck against political parties, and by rejecting their electoral, legal and moral legitimacy. This is simply preparing the ground for the next coup against democracy. It is ok to dislike Mr Zardari, and to oppose his presidency. Liking something does not make it right, and disliking something, does not make it wrong -- Pakistanis confuse the two at their own risk. Demonising Zardari today will have grave consequences for Pakistan's democratic future.

The writer is an independent political economist. Email: mosharraf@ gmail.com

Within the tradition of personifying national failure, General Ziaul Haq is perhaps the favourite of the English-language babus. It is amazing how Zia single handedly created religious fanaticism, turned the country into Ronald Reagan's hand-maiden and gave rise to all the evil that lurks in Tora Bora and straddles the Durand Line. If Zia is at the top of the list, Zulfi Bhutto is a not too distant second. The most recent addition to the arsenal of both liberals and conservatives is of course the recently retired and resigned Pervez Musharraf. In many ways he trumps both Bhutto and Zia in villainous magnitude – combining the supposed institutional appetite for fanaticism, with his personal appetite for the finer things in life. Now, the knives are sharpening and September 6 is almost upon us. If and when Mr Zardari finally does take office, many Pakistanis will cringe, and weep and turn off the television in disgust.

Before Mr Zardari is tagged with the label of national villain however, it would be useful for Pakistanis to take a long, hard look at where the country is today, and how it got here. The nervous ticks that a Zardari presidency is inspiring are rooted in three issues. First, presidential power to dissolve the assemblies, second, Mr Zardari's alleged corruption, and third, the symbolism of Mr Zardari as a non-traditional political figure, occupying the Aiwan-e-Sadr. Examining these in further detail reveals little to justify any logically consistent argument against a Zardari presidency.

The issue of the potential role of the president of Pakistan as a destabilising force that can dissolve assemblies is a legitimate fear. How that is Mr Zardari's fault however, is a mystery. Before being deposed, Nawaz Sharif had successfully restored the presidency to its figurehead role, without executive powers over parliament. That restoration had been over a decade in the making, given the horrible mutilation of institutions that occurred during General Zia's era. The presidency was not a powerful position in Pakistan again until December 2003, when the 17th Amendment was passed, restoring the lost lustre of dictatorship back to the presidency. Who gave the presidency these powers? It couldn't have been Mr Zardari himself, given that he was locked up in jail at the time. In fact, it was the parliament at the time, a parliament that was loaded with two parties of note, the so-called PML – Q and the right-coalition of the MMA. Simply put, any trepidation about the powers of the presidency has nothing to do with Mr Zardari. The credit or blame for any anxiety caused by the president's powers can be placed squarely at the feet of those two parties, and their task master at the time, the former president himself. At least on the count of draconian presidential powers then, we can be certain that Mr Asif Ali Zardari is not the one who enabled a presidency that has the power to interrupt the democratic process and facilitate dictatorship.

The second issue of concern in a Zardari presidency is of course the issue of his alleged corruption. This is not a complex issue at all. From a technical, legal standpoint Mr Zardari is innocent until proven guilty. At least three different governments over a span of almost twenty years have spent millions of dollars pursuing the cases against him. They have failed to deliver a guilty verdict. It is not Mr Zardari's fault that the system of justice in Pakistan is broken, and that the prosecutors of the agenda of accountability are incompetent. This is an issue on which clarity is of vital national importance. The simple perception of wrong doing is not good enough to prosecute someone. This is a principle upon which the national outrage over Dr Aafia Siddiqui's incarceration and extradition is based. It is also the principal upon which the legitimate Chief Justice, Mr Iftikhar Chaudhry based his observations about missing persons. Pakistanis need to be consistent. If Dr Afia and a generation of bearded Pakistanis are innocent until proven guilty, then so is Mr Asif Ali Zardari. Moreover, it is hard to take the entire anti-corruption, transparency and accountability agenda seriously, when those that are responsible for delivering transparency and accountability have sullied reputations themselves. No matter who the next president is, sooner or later, the government will reinitiate the accountability agenda. The country has tried this little game several times. First was the Ehtesaab Bureau under the leadership of Saifur Rehman -- himself a target of allegations of corruption. Then it was the National Accountability Bureau -- which practiced selective morality on the issue of corruption, indemnifying some categories of the corrupt and not others. Finally of course, it was General Musharraf that signed the NRO, not Mr Zardari. In a country where the moral boundaries are so widely and liberally defined, how can one man be held accountable for unproven sins, while everyone else is allowed fiscal impunity?

Finally, there is the issue of perception, the question of what a Zardari presidency would symbolise. Perception is a funny thing, because it is driven by our own biases and our own psychoses. What did a president in uniform symbolise? Where was middle class disgust and outrage when Ayub, Zia or Musharraf took over? What did a president who had no achievements of substance to his record other than to steadily and stealthily climb the ladders of power over a forty-year career represent? Where were the bureaucratic babus and their outrage when Ghulam Ishaq Khan not only became president, but proceeded to dissolve the assemblies not once, or twice, but three times? Where was English-language elite outrage or conservative self-righteous outrage when career sycophants like Wasim Sajjad, and Rafiq Tarrar became president? Or when a banker who was plucked from nowhere to not only become chairman of the Senate, governor of Sindh, but also caretaker prime minister, and then seamlessly back to chairman of the Senate? Where is the outrage at the conflict of interest that was invariably a part of Mohammedmian Soomro's back and forths between top positions in the government – without ever being elected to any office, by any citizen of Pakistan? In each case of course, there was always a smattering of boos, and some discomfort, but nothing like the wide-scale self-pity that Pakistanis are about to dive into.

One needn't be Rehman Malik, Salman Taseer or Hussain Haqqani to recognise and acknowledge one simple fact. A democratically elected, parliamentary powerful party has the right to elect a president of its choosing. No matter how much Mr Zardari is disliked by both liberal and conservative Pakistanis, his candidature is no worse than any of the other presidents Pakistan has had over the last two decades. At least in Mr Zardari's case, there is an element of democratic redemption that perhaps among his predecessors, only Rafiq Tarrar possessed.

The truth is that Pakistan's institutions are constantly being bludgeoned by the self-righteousness of the urban educated. It is they who provide the military with the legitimacy that allows well-meaning but illegitimate dictatorships to take root. Pakistan can begin its latest journey in democratic discovery the same way in which all previous journeys have begun. By stacking the deck against political parties, and by rejecting their electoral, legal and moral legitimacy. This is simply preparing the ground for the next coup against democracy. It is ok to dislike Mr Zardari, and to oppose his presidency. Liking something does not make it right, and disliking something, does not make it wrong -- Pakistanis confuse the two at their own risk. Demonising Zardari today will have grave consequences for Pakistan's democratic future.

The writer is an independent political economist. Email: mosharraf@ gmail.com

-

ByteDance’s New AI Video Model ‘Seedance 2.0’ Goes Viral

ByteDance’s New AI Video Model ‘Seedance 2.0’ Goes Viral -

Archaeologists Unearthed Possible Fragments Of Hannibal’s War Elephant In Spain

Archaeologists Unearthed Possible Fragments Of Hannibal’s War Elephant In Spain -

Khloe Kardashian Reveals Why She Slapped Ex Tristan Thompson

Khloe Kardashian Reveals Why She Slapped Ex Tristan Thompson -

‘The Distance’ Song Mastermind, Late Greg Brown Receives Tributes

‘The Distance’ Song Mastermind, Late Greg Brown Receives Tributes -

Taylor Armstrong Walks Back Remarks On Bad Bunny's Super Bowl Show

Taylor Armstrong Walks Back Remarks On Bad Bunny's Super Bowl Show -

James Van Der Beek's Impact Post Death With Bowel Cancer On The Rise

James Van Der Beek's Impact Post Death With Bowel Cancer On The Rise -

Pal Exposes Sarah Ferguson’s Plans For Her New Home, Settling Down And Post-Andrew Life

Pal Exposes Sarah Ferguson’s Plans For Her New Home, Settling Down And Post-Andrew Life -

Blake Lively, Justin Baldoni At Odds With Each Other Over Settlement

Blake Lively, Justin Baldoni At Odds With Each Other Over Settlement -

Thomas Tuchel Set For England Contract Extension Through Euro 2028

Thomas Tuchel Set For England Contract Extension Through Euro 2028 -

South Korea Ex-interior Minister Jailed For 7 Years In Martial Law Case

South Korea Ex-interior Minister Jailed For 7 Years In Martial Law Case -

UK Economy Shows Modest Growth Of 0.1% Amid Ongoing Budget Uncertainty

UK Economy Shows Modest Growth Of 0.1% Amid Ongoing Budget Uncertainty -

James Van Der Beek's Family Received Strong Financial Help From Actor's Fans

James Van Der Beek's Family Received Strong Financial Help From Actor's Fans -

Alfonso Ribeiro Vows To Be James Van Der Beek Daughter Godfather

Alfonso Ribeiro Vows To Be James Van Der Beek Daughter Godfather -

Elon Musk Unveils X Money Beta: ‘Game Changer’ For Digital Payments?

Elon Musk Unveils X Money Beta: ‘Game Changer’ For Digital Payments? -

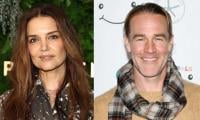

Katie Holmes Reacts To James Van Der Beek's Tragic Death: 'I Mourn This Loss'

Katie Holmes Reacts To James Van Der Beek's Tragic Death: 'I Mourn This Loss' -

Bella Hadid Talks About Suffering From Lyme Disease

Bella Hadid Talks About Suffering From Lyme Disease