Study reveals Antarctic krill produce three times more food boluses due to microplastics

Antarctic krill increased exponentially the rate at which they eject food when microplastics are present

A study from the University of Tasmania, Australia, has made a momentous discovery while observing the feeding behaviour of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba): They confirmed that krill export large amounts of carbon through their excrement.

Scientists have identified another way in which the swimming crustaceans may regulate Earth's climate by sending their leftovers down to the bottom of the sea.

The laboratory observations of krill filter-feeding behaviour further suggest that when the food is plentiful, such as during a phytoplankton bloom, the krill eject boluses of leftover food, a process that also contributes to biosequestration.

The study also revealed that microplastics in the water are a pernicious trigger for bolus formation and induce krill to eject food more frequently.

Tiny krill play a significant role in Earth’s carbon cycle. They are ubiquitous in the Southern Ocean and crucial to the Antarctic food web, thronging in such large numbers that they can be seen from space and nourishing seals, seabirds, penguins, and fish.

It has been observed that krill produce untold numbers of pellets that immediately sink to the seafloor, where the carbon remains locked away for at least a century.

In this connection, scientists estimate that the global biological carbon pump sequesters billions of metric tons of carbon each year, making it one of Earth’s largest natural carbon sinks.

However, in order to filter contaminants from the ocean water, a new filtration system is needed as krill are not effective decontaminants.

They compact the phytoplankton cells into a dense mass that they then clamp in their mouths.

Then they use their mandibles and other appendages to manipulate and rotate the mass and extract food for ingestion.

Ecologist Anita Butterly and her colleagues at the University of Tasmania in Australia examined this feeding behaviour in the laboratory by giving the krill distinct varieties and concentrations of phytoplankton and measuring the rate of bolus ejection.

Researchers found that higher phytoplankton concentrations correspond to more boluses ejection.

The team discovered that plastic was an accidental but useful contamination in some experiments.

Moreover, microplastics in the water stimulate krill to produce three times as many boluses comparable to other experiments.

It was a daunting experience as the team found that this research suggested that microplastic might cause the krill to reject food even when they are not full.

It adds to the growing concern that Antarctic krill are exposed to microplastics that might interfere with their digestion.

Additionally, previous studies suggested that krill ingesting microplastics may splinter further while releasing nanoplastics.

-

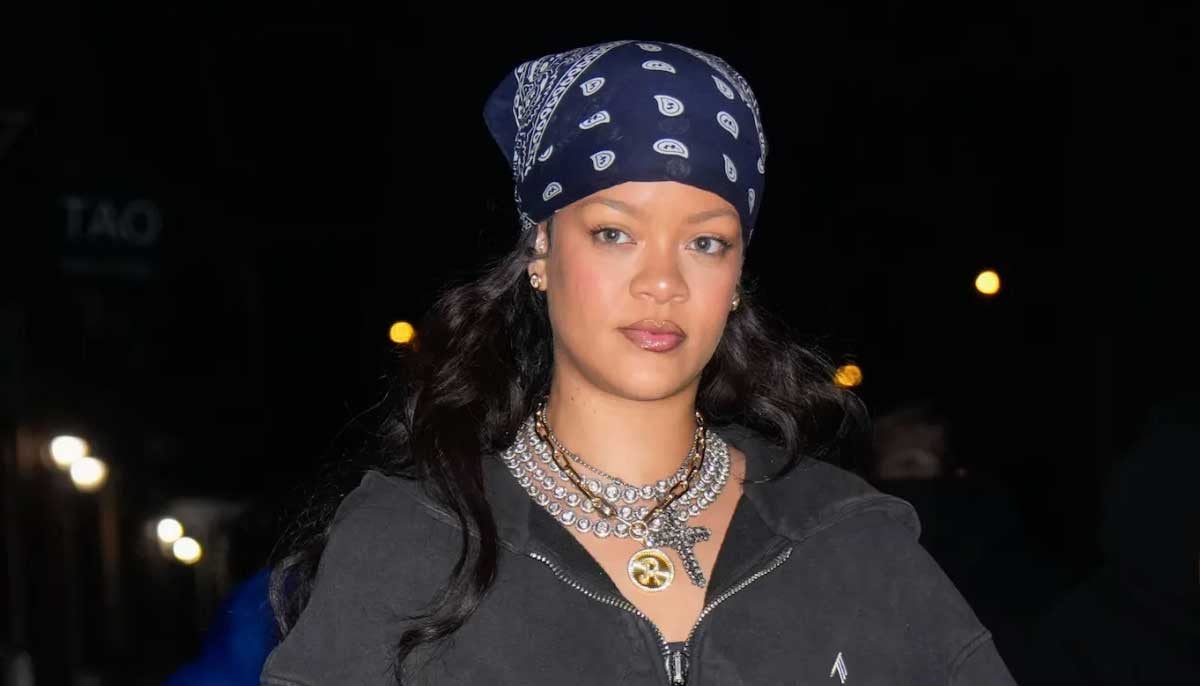

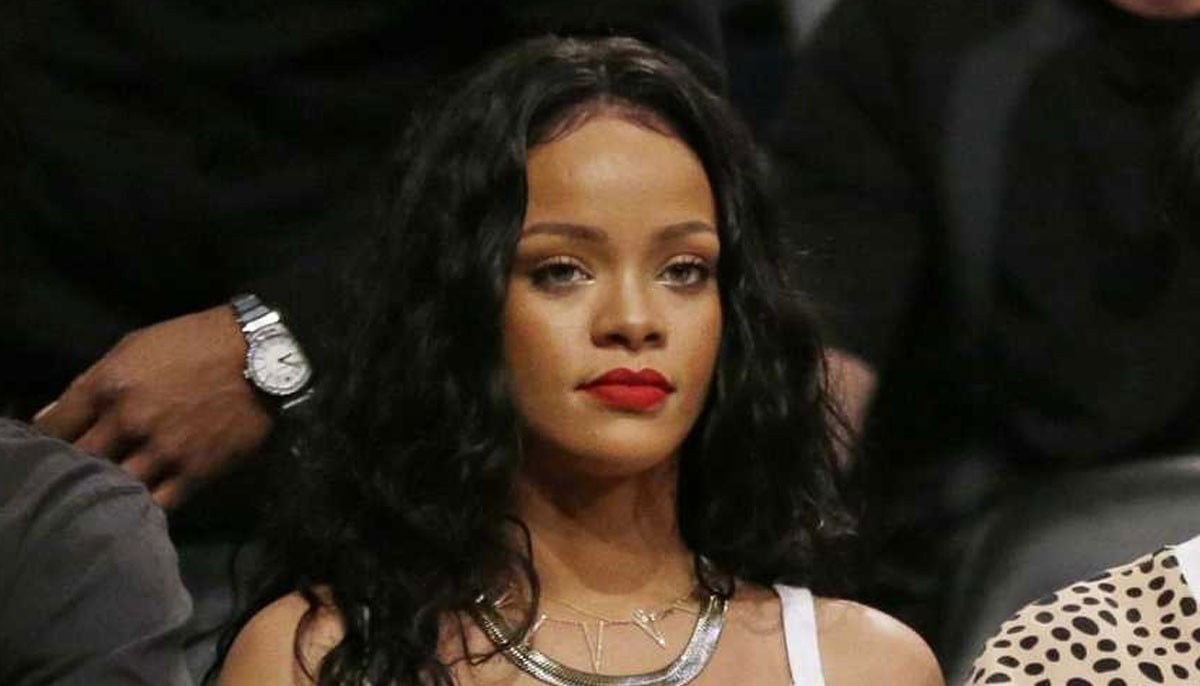

Rihanna shooter: Police reveal identity of singer's home shooting suspect

-

Stephanie Faracy talks about her role in 'Nobody Wants This' season 3

-

Selena Gomez pays sweet tribute to Benny Blanco on his birthday: 'I love you'

-

Stephanie Buttermore's final heartbreaking remarks about fiance Jeff Nippard

-

Christian Bale shares two cents on viral comparison amid 'The Bride!' release

-

Rihanna safe after attack on home in Beverly Hills

-

Jennifer Runyon, 'Ghostbusters' star, dies at 65

-

'Bridgerton' star Hannah Dodd recalls hilarious days from the sets of season 4