Australia climate visa: Tuvalu escape hatch from rising seas

Australia’s world-first climate visa offers a promising model for sinking island

The world has entered an era where climate change is no longer a distant warning, but a stark reality. Like the sword of Damocles, the threat precariously looms even larger on low-lying coastal nations.

Tuvalu is one of the ill-fated Polynesian island nations grappling with the existential threats of climate change.

Rising sea levels and its vulnerability to extreme weather events such as cyclones and storms, threaten the physical existence of the country.

According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), by 2050 most of Tuvalu’s infrastructure will be underwater.

Given the extreme vulnerability of Tuvalu, Australia has come forward with a climate visa for Tuvalu’s people, helping them to make choices in the face of slow-moving disaster.

World-first climate visa for low-lying nation

In November 2023, Australia signed the Falepili Union treaty with Tuvalu that aims to cover climate cooperation, dignified mobility, and shared security for the resources “in the face of the existential threat posed by climate change.”

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said it came in response to a request by Tuvalu “to safeguard the future of its people, identity and culture”.

In 2025, the Australian government has launched a “special mobility pathway.” Only up to 280 Tuvaluans will be granted the visa every year, allowing them to live, work or study in Australia.

An online ballot, opened on June 16 and closed on July 18, has been designed for the applicants to register. The random selection period will open on July 25 and conclude in January 2026.

Nearly one third of Tuvalu residents have applied for the Australian climate change visa programme, according to The Diplomat.

Benefits for selected candidates

The selected holders of the Pacific Engagement visa will be granted permanent residency in Australia for an indefinite period. Moreover, they can also travel freely in and out of the country.

The granted visa will also provide access to the country's Medicare system, childcare subsidies, education and vocational facilities at the same subsidisation as Australian citizens.

According to Jane McAdam, a law professor and expert in refugee law at the University of New South Wales, “for some people it might be an opportunity to get their children a great education in Australia. For others, it will be a job opportunity, maybe sending remittances home,” calling it a safety net for Tuvaluans.

Could climate visas be replicated by other states?

Besides Tuvalu, the Maldives, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands face existential threats from climate-induced weather events. In this backdrop, these island nations could benefit from regional climate-mobility frameworks.

The US has implemented Compacts of Free Association with Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau, allowing their citizens to live and work freely in the USA. Unlike Australian climate arrangements, the US offers little access to public service benefits.

In 2023, ministers from African member states vouched for the Kampala Ministerial Declaration on Migration, Environment, and Climate Change, pledging coordinated responses for people who want to migrate due to climate change.

Is Australia’s climate visa a model for the world?

According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), climate change and extreme weather events could lead to 1.2 billion climate migrants by 2050.

Given the severity and frequency of calamities, there is a need of the hour to implement a climate visa model for extremely climate-threatened countries.

However, the key challenges are also involved in this model including sovereignty issues, migration-related difficulties, and constrained access to social services and benefits. Moreover, the scarcity of resources could further erode social fabric.

According to Gaia Vince, the author of Nomad Century: How Climate Migration Will Reshape Our World, North nations could also leverage young and vibrant migrants for labour shortages in the face of an aging population.

-

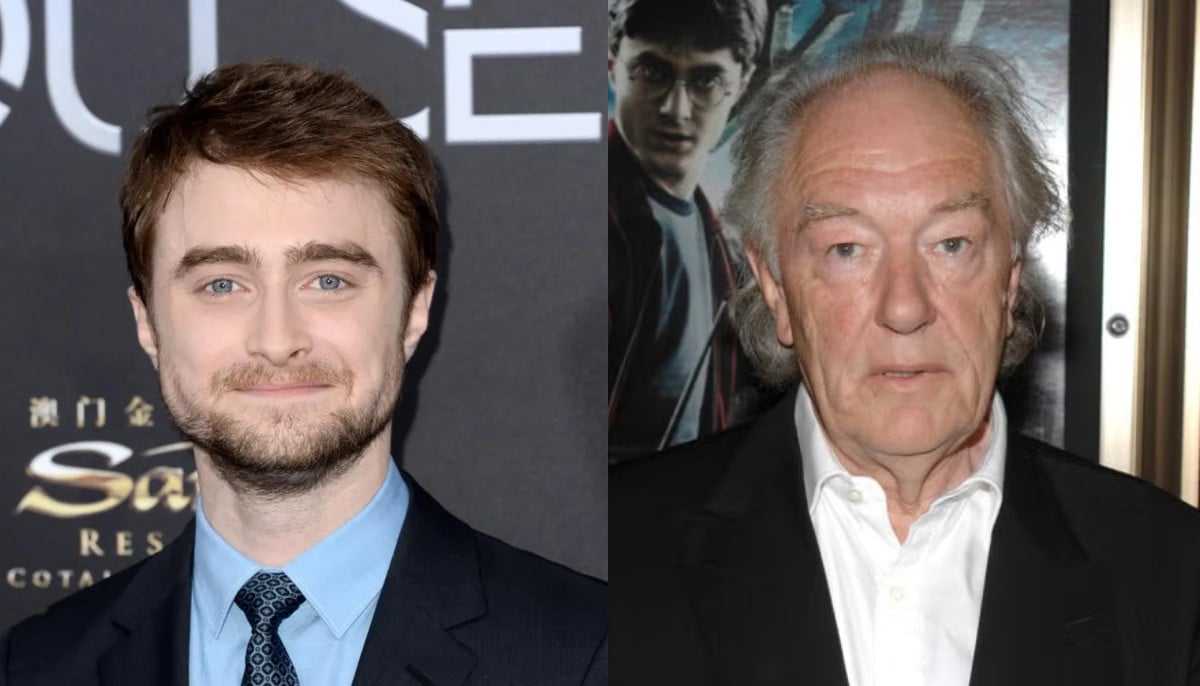

'Harry Potter' alum Daniel Radcliffe gushes about unique work ethic of late co star Michael Gambon

-

Paul McCartney talks 'very emotional' footage of late wife Linda in new doc

-

It's a boy! Luke Combs, wife Nicole welcome third child

-

Gemma Chan reflects on 'difficult subject matter' portrayed in 'Josephine'

-

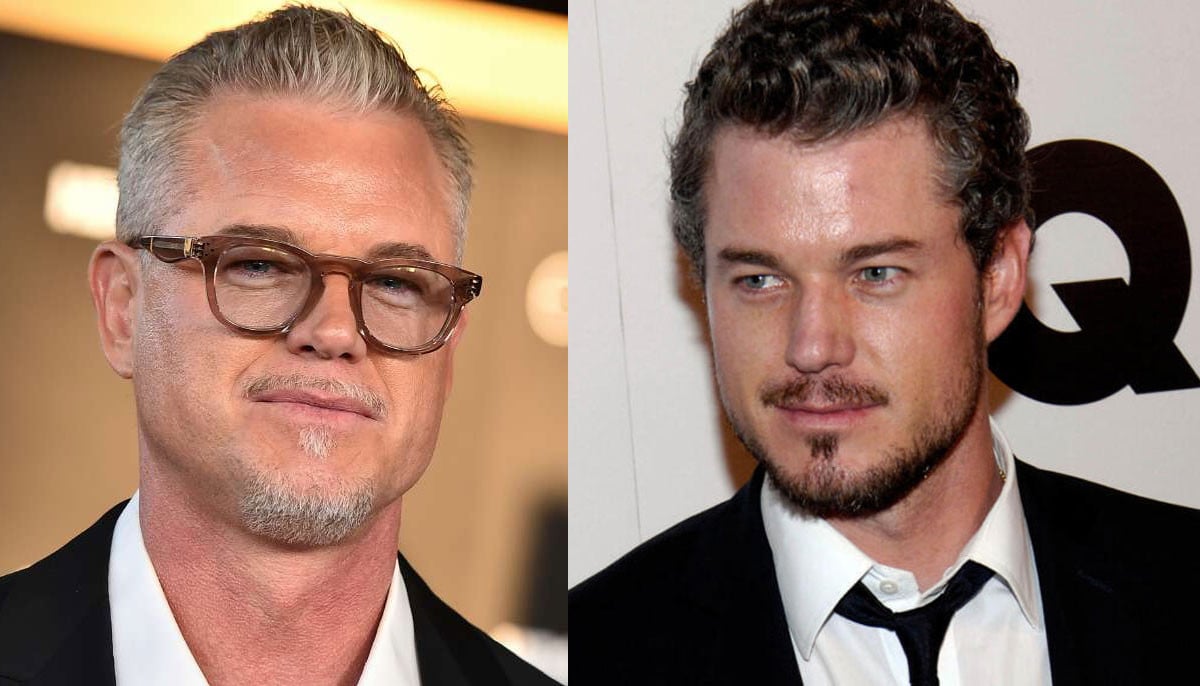

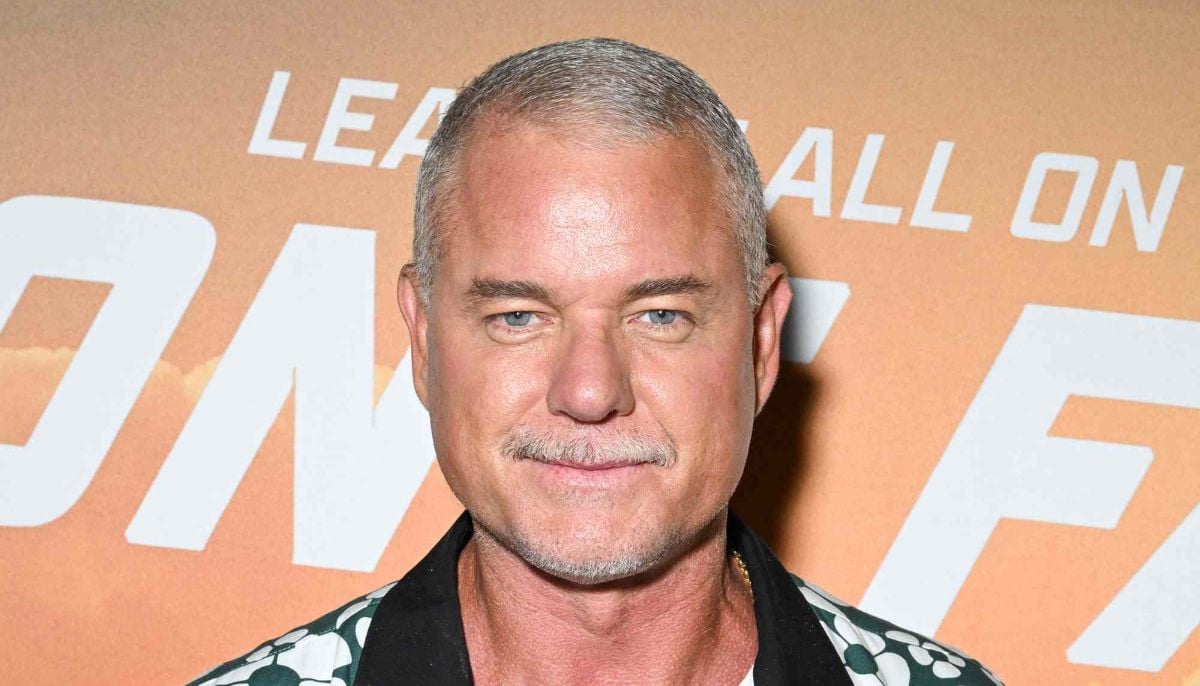

Rebecca Gayheart unveils what actually happened when husband Eric Dane called her to reveal his ALS diagnosis

-

Eric Dane recorded episodes for the third season of 'Euphoria' before his death from ALS complications

-

Jennifer Aniston and Jim Curtis share how they handle relationship conflicts

-

Apple sued over 'child sexual abuse' material stored or shared on iCloud