History never forgets

Justice Patel was next in line to become the CJP for eight years but chose principle over position

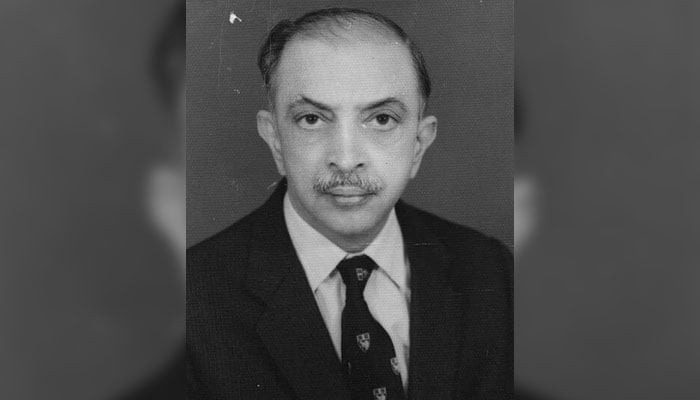

Today would have been the 101st birthday of Justice Dorab Framrose Patel. More than a century after his birth, his legacy remains powerfully relevant to Pakistan’s legal and democratic journey.

Born in Bombay, British India, he studied law and economics at Bombay University and the London School of Economics. After returning to Pakistan, he rose swiftly through the judicial ranks. But it is not his ascent that history remembers, it is the principled manner in which he chose to step down.

In 1981, under General Ziaul Haq’s martial law regime, judges were asked to retake their oaths under a Provisional Constitutional Order (PCO). Justice Patel refused. He was next in line to become the chief justice of Pakistan for eight years but chose principle over position.

His defiance still echoes especially today, when judicial independence is again under threat. Justice Patel remains a symbol of moral clarity and a reminder that the true strength of a judge lies not in office, but in conscience. In a system where justice too often bends to power, his life stands as a rare and enduring example of integrity.

To his credit, Justice Patel never disowned his own complicity. In ‘Testament of a Liberal’, he candidly acknowledged having once acquiesced under similar pressure. During General Yahya Khan’s regime, he and other judges continued to serve under martial law following a directive from the Supreme Court’s leadership. Reflecting on that decision, he wrote: “We agreed and decided to work as judges under martial law, and the people of Pakistan rightly took our decision to mean that we had validated General Yahya’s regime.”

Years later, when presented with the same test under General Zia, he chose differently. He stepped down. He chose not silence, but resistance.

When judicial benches were being reshaped to legitimize authoritarianism, Justice Patel stood firm. Judicial legitimacy, he showed, is not a matter of numbers, it is a matter of courage. As Justice Shadi Lal, the first Indian chief justice of the Lahore High Court, once observed: “Justice is not to be measured by the number of its judges, for all judges, unfortunately, do not always do justice.”

Justice Patel did.

That same courage marked his dissent in one of Pakistan’s darkest judicial chapters during the trial of prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Justice Patel was among the three dissenting judges who refused to endorse the death sentence, citing uncorroborated testimony and procedural violations. It was a principled stand against judicial complicity in political vengeance. And it came at a cost.

But history did not forget him.

In 2024, four decades later, Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, writing in his additional note to the Supreme Court’s opinion in the Bhutto reference, paid rare tribute to Justice Patel. He acknowledged that had more judges shown similar courage, the judicial failure in Bhutto’s case might have been avoided. It was both an institutional reckoning and a powerful affirmation of Justice Patel’s legacy.

More importantly, Justice Patel was not the last judge to forgo high office rather than surrender judicial conscience. Others have since quietly followed his example declining elevation in order to uphold principle over power. They, too, belong to the quiet lineage Justice Patel helped define where defiance matters more than submission.

The judiciary is not beyond redemption. It is a resilient institution, capable of self-correction. But that resilience depends on the conviction of individual judges. The defining moments in judicial history rarely emerge from consensus, they often begin with a single act of principled defiance.

Justice Patel understood this. His resignation was not a gesture, it was a stand. He reminded us that the honour of judicial office lies not in its privileges, but in the injustice a judge refuses to legitimize.

Even after leaving the bench, he remained a tireless defender of rights. He co-founded the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, worked with Amnesty International, and championed civil liberties long after stepping away from formal power.

On his 101st birthday, there are no medals or accolades that can truly honour him. What would is a judiciary that lives by the standard he set, that fidelity to the Constitution is non-negotiable even when it demands sacrifice. Once again, Pakistan’s judiciary stands at a crossroads. The pressures may be different but the question remains the same: will our courts stand with the constitution or with those who seek to bend it?

Justice Dorab Patel answered that question with quiet, unwavering resolve. He showed that a judge’s true strength lies not in holding power, but in having the courage to resist it.

Because history never forgets nor forgives.

The writer is a judicial law clerk to the senior puisne judge at the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

-

Patriots' WAGs Slam Cardi B Amid Plans For Super Bowl Party: She Is 'attention-seeker'

Patriots' WAGs Slam Cardi B Amid Plans For Super Bowl Party: She Is 'attention-seeker' -

Martha Stewart On Surviving Rigorous Times Amid Upcoming Memoir Release

Martha Stewart On Surviving Rigorous Times Amid Upcoming Memoir Release -

Prince Harry Seen As Crucial To Monarchy’s Future Amid Andrew, Fergie Scandal

Prince Harry Seen As Crucial To Monarchy’s Future Amid Andrew, Fergie Scandal -

Chris Robinson Spills The Beans On His, Kate Hudson's Son's Career Ambitions

Chris Robinson Spills The Beans On His, Kate Hudson's Son's Career Ambitions -

18-month Old On Life-saving Medication Returned To ICE Detention

18-month Old On Life-saving Medication Returned To ICE Detention -

Major Hollywood Stars Descend On 2026 Super Bowl's Exclusive Party

Major Hollywood Stars Descend On 2026 Super Bowl's Exclusive Party -

Cardi B Says THIS About Bad Bunny's Grammy Statement

Cardi B Says THIS About Bad Bunny's Grammy Statement -

Sarah Ferguson's Silence A 'weakness Or Strategy'

Sarah Ferguson's Silence A 'weakness Or Strategy' -

Garrett Morris Raves About His '2 Broke Girls' Co-star Jennifer Coolidge

Garrett Morris Raves About His '2 Broke Girls' Co-star Jennifer Coolidge -

Winter Olympics 2026: When & Where To Watch The Iconic Ice Dance ?

Winter Olympics 2026: When & Where To Watch The Iconic Ice Dance ? -

Melissa Joan Hart Reflects On Social Challenges As A Child Actor

Melissa Joan Hart Reflects On Social Challenges As A Child Actor -

'Gossip Girl' Star Reveals Why She'll Never Return To Acting

'Gossip Girl' Star Reveals Why She'll Never Return To Acting -

Chicago Child, 8, Dead After 'months Of Abuse, Starvation', Two Arrested

Chicago Child, 8, Dead After 'months Of Abuse, Starvation', Two Arrested -

Travis Kelce's True Feelings About Taylor Swift's Pal Ryan Reynolds Revealed

Travis Kelce's True Feelings About Taylor Swift's Pal Ryan Reynolds Revealed -

Michael Keaton Recalls Working With Catherine O'Hara In 'Beetlejuice'

Michael Keaton Recalls Working With Catherine O'Hara In 'Beetlejuice' -

King Charles, Princess Anne, Prince Edward Still Shield Andrew From Police

King Charles, Princess Anne, Prince Edward Still Shield Andrew From Police