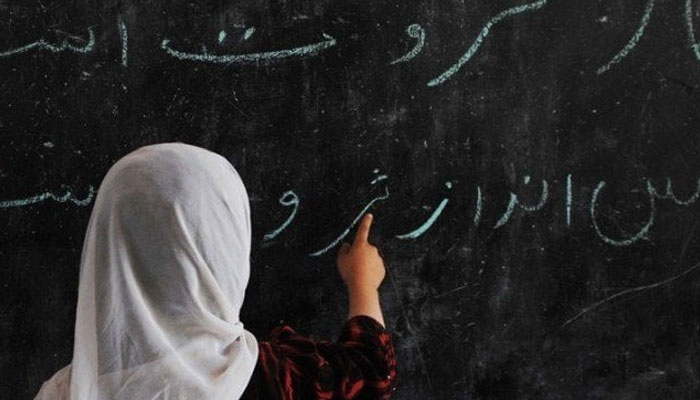

A language of your own

Fostering multilingualism is essential for preserving identity and promoting inclusivity

For decades, Pakistan has pursued an official policy of promoting Urdu as a national language to encourage harmony and cohesion. The underlying belief is that a common language fosters national unity. However, the pursuit of uniformity should not come at the cost of diversity and difference. In a nation as rich in cultural and linguistic heritage as Pakistan, fostering multilingualism is essential for preserving identity and promoting inclusivity. As we mark International Mother Language Day today, it is worth reflecting on Pakistan’s linguistic landscape. More than 70 languages are spoken across the country, representing a tapestry of cultures and histories. Yet, many of these languages face the threat of extinction. According to Unesco, 27 languages in Pakistan are endangered, with 18 of them native to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, former Fata and Gilgit-Baltistan. The reasons range from the small size of native communities to geographical isolation, political marginalisation and even displacement due to conflict. Among these endangered languages is Yidgha from the Chitral district, now spoken by fewer than 5,000 people. In the same region, Urmari too teeters on the brink of extinction due to displacement caused by military operations.

With each dying language, we lose centuries of accumulated knowledge, tradition and identity. Pakistan’s struggle with issues of identity and ethnicity is linked to its historical reluctance to fully embrace its diversity. The insistence on a singular national identity, predominantly defined by Urdu, has contributed to feelings of alienation among ethnic and linguistic minorities. Pakistan’s education system reflects this exclusionary approach. Despite the existence of over 70 languages, only Urdu and English are given full official recognition. This linguistic hierarchy is directly linked to Pakistan’s poor educational outcomes. According to Early Grade Reading Assessment tests conducted in 2013, most students in Pakistan could not fully read a 60-word passage in Urdu, let alone comprehend it. The current linguistic exclusion in the country contributes to educational failure, social stratification and limited economic opportunities, trapping people outside an Anglo-Urdu bubble that is far smaller than it appears.

The solution lies in embracing multilingualism and promoting linguistic diversity within Pakistan’s education system. Studies have shown that children learn best in their mother tongue, particularly in early education. Recognising this, some educationists say that Pakistan should introduce regional languages as mediums of instruction alongside Urdu and English. Regional languages could be offered as subjects at all educational levels, including in provinces where they are not traditionally spoken. Pakistan must realise that accepting all languages, big and small, as equal in standing is not a threat to national unity. On the contrary, it is a means of fostering national integration and social harmony. Our diverse linguistic landscape is a reflection of our cultural wealth. It is time to shed the fear that multilingualism weakens nations. In fact, nations that embrace their linguistic diversity are stronger, more cohesive, and more resilient. By promoting mother languages and encouraging multilingual education, Pakistan can build a more inclusive society that celebrates its rich cultural heritage.

-

Liza Minelli Makes Bombshell Claim About Late Mother Judy Garland’s Struggle With Drugs

Liza Minelli Makes Bombshell Claim About Late Mother Judy Garland’s Struggle With Drugs -

Shipping Giant Maersk Halts Suez Canal, Bab El-Mandeb Sailings Amid Escalating Conflict

Shipping Giant Maersk Halts Suez Canal, Bab El-Mandeb Sailings Amid Escalating Conflict -

Matthew McCoughaney Reveals One 'gift' He Achieved With Losing Nearly 50 Pounds

Matthew McCoughaney Reveals One 'gift' He Achieved With Losing Nearly 50 Pounds -

'Scream 7' Breaks Box Office Record Of Slasher Franchise: 'We Are Grateful'

'Scream 7' Breaks Box Office Record Of Slasher Franchise: 'We Are Grateful' -

Bolivian Military Plane Crash Death Toll Rises To 20

Bolivian Military Plane Crash Death Toll Rises To 20 -

'Sinners' Star Blasts Major Media Company For 2026 BAFTAs Incident

'Sinners' Star Blasts Major Media Company For 2026 BAFTAs Incident -

Inside Scooter Braun, Sydney Sweeney's Plans To Settle Down, Have A Baby

Inside Scooter Braun, Sydney Sweeney's Plans To Settle Down, Have A Baby -

Bobby Moynihan Makes Shock Admission About 1994's 'The Lion King' As He Steps Into New Role

Bobby Moynihan Makes Shock Admission About 1994's 'The Lion King' As He Steps Into New Role -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Delivers Shocking Twist, Director Explains Why It Was Important

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Delivers Shocking Twist, Director Explains Why It Was Important -

Missing Florida Man Found Alive After Days Trapped In 'quick-sand Like Mud'

Missing Florida Man Found Alive After Days Trapped In 'quick-sand Like Mud' -

Hollywood Producers Sound Alarm Over Major Fear On Paramount-Warner Bros. Deal

Hollywood Producers Sound Alarm Over Major Fear On Paramount-Warner Bros. Deal -

Sea Tragedy: One Dead, Several Missing After Tugboat Sinks Off South Africa

Sea Tragedy: One Dead, Several Missing After Tugboat Sinks Off South Africa -

King Charles’ Abdication: Where The Monarch Stands On Giving Up The Throne To William

King Charles’ Abdication: Where The Monarch Stands On Giving Up The Throne To William -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Stars Comment On Their Returns For Fifth Season As Benedict, Sophie's Love Story Wraps Up

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Stars Comment On Their Returns For Fifth Season As Benedict, Sophie's Love Story Wraps Up -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Finally Land In Big Trouble Over Sarah, Andrew Scandal

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Finally Land In Big Trouble Over Sarah, Andrew Scandal -

'Bridgerton' Star Phoebe Dynevor Revealed Her Most Hated Trait

'Bridgerton' Star Phoebe Dynevor Revealed Her Most Hated Trait