“Azhar” is an unmitigated disaster only because of its relentless idolization of an obviously flawed man. A more subtle, honest and casual admission of the cricketer’s repeated lapses in judgments would perhaps have made him look less greedy, and more deserving of sympathy and forgiveness, writes Anupriya Kumar.

Mohammad Azharuddin, the cricketer on whose life Tony D’Souza’s “Azhar” is based, struck a hundred in his first three test matches. It was a glorious start to a fairly successful career – until his implication in a match-fixing scandal and a lifetime ban from the cricket pitch.

Unlike the man himself, the movie does not impress for any stretch of time. It slips out of control from the opening scene, in which disgruntled cricketer Manoj (a clear reference to Manoj Prabhakar, the player who accused Azharuddin and others of throwing matches in the late 1990s) caricaturishly plots a sting operation.

Then you have shots of the titular character smashing fours and sixes around the cricket ground, with embarrassingly fake images of crowds cheering in the background. These shots are spliced with scenes to establish Azhar’s power, status and influence – you see the man stepping out of expensive cars, posing for the camera, and being surrounded by people either fawning or expressing envy. All this right after (or before – it’s hard to keep track sometimes) a cricket board member makes allegations against him and shames him with unabashed theatricality.

The first 20 minutes of “Azhar” establish a pattern of success and failure, highs and lows, heartbreaking losses and thumping wins in quick succession.

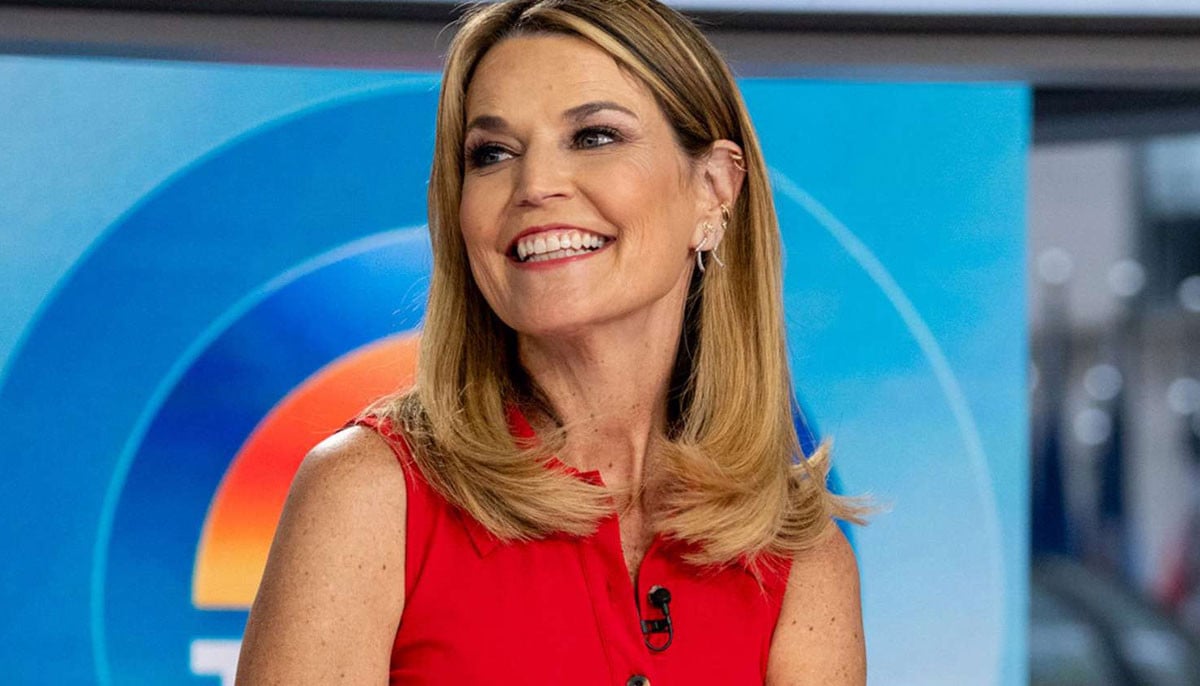

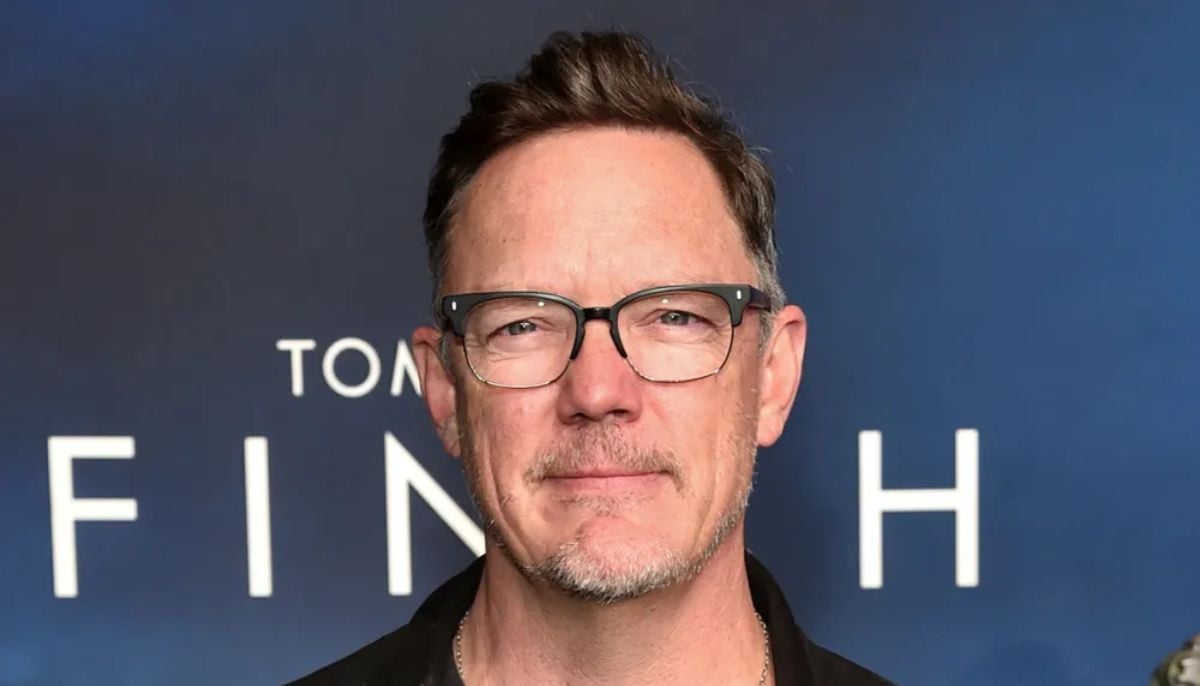

Emran Hashmi and Prachi Desai in a still from the movie "Azhar"

As if the title of the movie wasn’t enough, the director goes the extra mile to show exactly whose side he is on in the sordid match-fixing saga. The film’s makers throw their weight behind Azharuddin, portraying him as someone more wronged than wrong, a man of immense talent and mostly steady morals who was simply a victim of bad circumstances and people far more wicked than him. It looks a bit ridiculous because almost as a matter of rule, Azhar chooses the exact opposite of the morally sound choice right after delivering sermons to others – choices that range from starting an extra-marital affair, accepting a bribe, and throwing matches.

There’s a distinct feeling of things being rushed, as if the movie had a lot to tell but not enough time. From Azharuddin’s early life and the way his maternal grandfather influenced his early years to his arrival in Mumbai and his selection in the national team – everything is represented with flashy montages, tacky dialogue and an ear-splitting background score.

The narrative jumps back and forth in time and it’s hard to tell the difference immediately, because the filmmaker didn’t find recreating the past accurately worth his time or effort.

Lara Emraan Hashmi tries his best but his efforts are patchy and mostly lacklustre. He gets Azharuddin’s body language and mannerisms right to an extent but only sometimes, as if staying in the role throughout the film was too much to ask. Prachi Desai is convincing as the cricketer’s selfless first wife Naureen, who never leaves her husband’s side despite being rejected by him in the most public way possible.

Lara Datta looks confident as the career-driven, no-nonsense prosecution lawyer. Aditya Roy Kapoor hams and overacts as Azharuddin’s friend and counsel. His wig and the fake bald patch may distract some viewers. Nargis Fakhri looks radiant as Sangeeta, Azharuddin’s second wife.

Good scenes are few and far in between. I enjoyed the part where Azharuddin’s mother tells him to get married, right up to his first interaction with Naureen.

“Azhar” is an unmitigated disaster only because of its relentless idolization of an obviously flawed man. A more subtle, honest and casual admission of the cricketer’s repeated lapses in judgments would perhaps have made him look less greedy, and more deserving of sympathy and forgiveness.

-

Timothée Chalamet reveals rare impact of not attending acting school on career

-

Liza Minnelli gets candid about her struggles with substance abuse post death of mum Judy Garland

-

'Saturday Night Live' star Will Forte reveals how he feels about returning to the show after 2010 exit

-

Eric Dane's family shares heartbreaking statement after his death

-

'Never Have I Ever' star Maitreyi Ramakrishnan lifts the lid on how she avoids drama at coffee shops due to her name

-

Chyler Leigh pays moving homage to 'Grey’s Anatomy' co-star Eric Dane: 'He was amazing'

-

Matthew Lillard admits fashion trends are not his 'forte'

-

Anna Sawai opens up on portraying Yoko Ono in Beatles film series