Policing the police

The very thesis of ‘state monopoly on violence’ or the ‘monopoly of legitimate use of physical force’ was first expounded by German sociologist Max Weber a century ago. This thesis essentially maintains that the state alone has the right to use or authorise the use of physical force. In this

By Mohsin Raza Malik

June 06, 2015

The very thesis of ‘state monopoly on violence’ or the ‘monopoly of legitimate use of physical force’ was first expounded by German sociologist Max Weber a century ago. This thesis essentially maintains that the state alone has the right to use or authorise the use of physical force. In this context, he defines the state as a “human community that successfully claims the monopoly of legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.”

Significantly restricting the individual’s right to use physical force in a polity, now this Weberian concept has somehow become a defining characteristic of the modern state. Weber also recognised the police and the military as the two main instruments of the state for the dispensation of its so-called monopoly on violence.

Police is the civil force of a state whose job is to enforce the law, prevent and solve crimes, and maintain public order and safety. In order to enable the police to effectively discharge these functions, the state adequately empowers this organisation. It essentially delegates its authority to the police, including the monopoly of legitimate use of physical force.

However, this authority is by no means arbitrary, unrestrained and unlimited. The police are always supposed to exercise this authority within defined parameters and legal framework. An effective regulatory mechanism is always required to regulate the behaviour and actions of the police.

There has been a tendency among the members of the police force to overstep and misuse their authority. The recent unfortunate Daska incident necessarily reflects this inherent tendency of the police in Pakistan. The incident sparked violent agitation and strong protest by the lawyer community throughout the country. This incident is not the first of its kind.

Just like the typical who-will-guard-the-guardian conundrum, there has also been a sort of policing-the-police dilemma in Pakistan. The trigger-happy attitude of the police have become its two dominant characteristics. In the absence of any strong accountability mechanism, the police have frequently been found misusing and abusing their authority.

Pakistan inherited the colonial-era Police Act, 1861 at the time of its independence. This law has extensively been criticised in the country on various grounds. However, despite all its flaws and shortcomings, this act provided an effective institutional check on the unfettered powers of the police. Under this law, from the sub-divisional magistrate to district magistrate, a hierarchy of executive magistrates was established to oversee and assist the police in important policing functions. These executive magistrates acted as intermediaries between the public and the police to avoid any untoward situation during public agitation and protest. Had we not instantly abolished this police-cum-magisterial system in the country, we would have avoided tragic incidents like Model Town and Daska in Punjab.

Replacing the Police Act 1861, the Police Order, 2002 was introduced by Gen Pervez Musharraf as part of his so-called devolution of power plan in Pakistan. Trying to make the police a ‘professional, service-oriented and answerable’ organisation, the architect of this policing system tried to redefine the police’s role, duties and responsibilities.

Under this law, in the form of public safety commissions at the national, provincial and district levels, various statutory regulatory bodies were devised to regulate policing, and exercise some control over police officials in the interest of general public. Owing to lack of political will, and non-existence of local bodies institutions, these public safety commissions could not ever be constituted. In the absence of these public safety commissions, this newly-devised policing system has also failed to achieve its desired objectives.

Ignoring the structural aspect of the police organisation, the Police Order, 2002 has only introduced some functional changes in the policing system. It didn’t focus on matters relating to recruitment, training and capacity-building of the police. As a matter of fact, the replacement of the Police Act, 1861 with the Police Order, 2002 was merely an old-wine-in-new-bottle sort of case. This new law has only retained the old stuff under a new nomenclature. Calling an IGP a PPO, a DIG an RPO and a district SP a DPO can hardly help set things right.

The Station House Officer (SHO) wields enormous powers under the law of the land. The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) allows the SHO to exercise extensive discretionary powers relating to the investigation, arrest, detention and release of an accused person. He is also generally termed as the backbone of the entire policing structure in the country. Usually a non-gazetted low-grade officer is appointed as SHO in police stations in the country. Besides this, his political affiliations determine his transfers and postings. Consequently, instead of becoming a crime-fighter, the SHO has played an instrumental role in giving rise to the notorious so-called ‘thana culture’ in Pakistan.

In order to improve the general state of policing in the country, the government should focus on the substance instead of being obsessed with the form of the police organisation. There should also be an efficient institutional mechanism to regulate conduct, and exercise an effective check on the arbitrary powers of the police officials.

The writer is a Lahore-based lawyer.

Email: mohsinraza.malik@ymail.com

Significantly restricting the individual’s right to use physical force in a polity, now this Weberian concept has somehow become a defining characteristic of the modern state. Weber also recognised the police and the military as the two main instruments of the state for the dispensation of its so-called monopoly on violence.

Police is the civil force of a state whose job is to enforce the law, prevent and solve crimes, and maintain public order and safety. In order to enable the police to effectively discharge these functions, the state adequately empowers this organisation. It essentially delegates its authority to the police, including the monopoly of legitimate use of physical force.

However, this authority is by no means arbitrary, unrestrained and unlimited. The police are always supposed to exercise this authority within defined parameters and legal framework. An effective regulatory mechanism is always required to regulate the behaviour and actions of the police.

There has been a tendency among the members of the police force to overstep and misuse their authority. The recent unfortunate Daska incident necessarily reflects this inherent tendency of the police in Pakistan. The incident sparked violent agitation and strong protest by the lawyer community throughout the country. This incident is not the first of its kind.

Just like the typical who-will-guard-the-guardian conundrum, there has also been a sort of policing-the-police dilemma in Pakistan. The trigger-happy attitude of the police have become its two dominant characteristics. In the absence of any strong accountability mechanism, the police have frequently been found misusing and abusing their authority.

Pakistan inherited the colonial-era Police Act, 1861 at the time of its independence. This law has extensively been criticised in the country on various grounds. However, despite all its flaws and shortcomings, this act provided an effective institutional check on the unfettered powers of the police. Under this law, from the sub-divisional magistrate to district magistrate, a hierarchy of executive magistrates was established to oversee and assist the police in important policing functions. These executive magistrates acted as intermediaries between the public and the police to avoid any untoward situation during public agitation and protest. Had we not instantly abolished this police-cum-magisterial system in the country, we would have avoided tragic incidents like Model Town and Daska in Punjab.

Replacing the Police Act 1861, the Police Order, 2002 was introduced by Gen Pervez Musharraf as part of his so-called devolution of power plan in Pakistan. Trying to make the police a ‘professional, service-oriented and answerable’ organisation, the architect of this policing system tried to redefine the police’s role, duties and responsibilities.

Under this law, in the form of public safety commissions at the national, provincial and district levels, various statutory regulatory bodies were devised to regulate policing, and exercise some control over police officials in the interest of general public. Owing to lack of political will, and non-existence of local bodies institutions, these public safety commissions could not ever be constituted. In the absence of these public safety commissions, this newly-devised policing system has also failed to achieve its desired objectives.

Ignoring the structural aspect of the police organisation, the Police Order, 2002 has only introduced some functional changes in the policing system. It didn’t focus on matters relating to recruitment, training and capacity-building of the police. As a matter of fact, the replacement of the Police Act, 1861 with the Police Order, 2002 was merely an old-wine-in-new-bottle sort of case. This new law has only retained the old stuff under a new nomenclature. Calling an IGP a PPO, a DIG an RPO and a district SP a DPO can hardly help set things right.

The Station House Officer (SHO) wields enormous powers under the law of the land. The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) allows the SHO to exercise extensive discretionary powers relating to the investigation, arrest, detention and release of an accused person. He is also generally termed as the backbone of the entire policing structure in the country. Usually a non-gazetted low-grade officer is appointed as SHO in police stations in the country. Besides this, his political affiliations determine his transfers and postings. Consequently, instead of becoming a crime-fighter, the SHO has played an instrumental role in giving rise to the notorious so-called ‘thana culture’ in Pakistan.

In order to improve the general state of policing in the country, the government should focus on the substance instead of being obsessed with the form of the police organisation. There should also be an efficient institutional mechanism to regulate conduct, and exercise an effective check on the arbitrary powers of the police officials.

The writer is a Lahore-based lawyer.

Email: mohsinraza.malik@ymail.com

-

King Charles Walks By As Protestors Cry: 'What Did You Know About Andrew?'

King Charles Walks By As Protestors Cry: 'What Did You Know About Andrew?' -

Watch: Prince William Buttons His Coat And Walks With Kate Amid Trouble

Watch: Prince William Buttons His Coat And Walks With Kate Amid Trouble -

Kris Jenner Steps In To Support Her Friend Meghan Markle

Kris Jenner Steps In To Support Her Friend Meghan Markle -

Scott Baio Reacts To Sudden Death Of 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Jennifer Runyon

Scott Baio Reacts To Sudden Death Of 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Jennifer Runyon -

Emilia, James Van Der Beek's Daughter, Shares How To Fight Grief After Losing A Loved One

Emilia, James Van Der Beek's Daughter, Shares How To Fight Grief After Losing A Loved One -

Rihanna Shooter: Police Reveal Identity Of Singer's Home Shooting Suspect

Rihanna Shooter: Police Reveal Identity Of Singer's Home Shooting Suspect -

Dolly Parton Ready To Marry Again?

Dolly Parton Ready To Marry Again? -

Savannah Guthrie Breaks Cover As Search For Mom Nancy Intensifies

Savannah Guthrie Breaks Cover As Search For Mom Nancy Intensifies -

Jennifer Lopez Shares Emotional Post After Discussing Split With Marc Anthony

Jennifer Lopez Shares Emotional Post After Discussing Split With Marc Anthony -

Andrew's Escape Plan Just Hit Unexpected Roadblock: 'Huge Blow'

Andrew's Escape Plan Just Hit Unexpected Roadblock: 'Huge Blow' -

Jessica Alba And Danny Ramirez Send Strong Message: Ignore Joe Burrow Rumours

Jessica Alba And Danny Ramirez Send Strong Message: Ignore Joe Burrow Rumours -

Dakota Johnson Leaves Fans Speechless With Calvin Klein Ad

Dakota Johnson Leaves Fans Speechless With Calvin Klein Ad -

Stephanie Faracy Talks About Her Role In 'Nobody Wants This' Season 3

Stephanie Faracy Talks About Her Role In 'Nobody Wants This' Season 3 -

Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Receive Fresh Warning

Princess Eugenie, Beatrice Receive Fresh Warning -

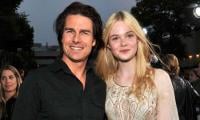

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards -

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer