Census 2017

The release of provisional census data by the Ministry of Statistics confirms population trends that many had been expecting. Pakistan’s total population, excluding Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan, stands at 207.774 million. Compared with the 1998 census, there has been a 57 percent increase in our population in the last 19 years. The population increase confirms the sheer scale of governance and service delivery challenges that policymakers must deal with. The population growth rate remains around 2.4 percent, suggesting that whatever family planning programmes have been undertaken by the state have turned out to be ineffectual. One alarming fact to have emerged is a growing gender gap. There are almost five million more men in Pakistan than women. With everything else being equal, women generally have a longer life expectancy than men. It would be important to see what age groups this gender gap is most pronounced in before declaring a cause for concern – but one may point to the preference for male children as a possible source for this alongwith the lack of women’s access to healthcare. Punjab is still the province with the largest population – at around 110 million. Sindh is second with almost 48 million while Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are home to 12 million and 30.5 million respectively. These numbers will be important for the next NFC Award and provincial distribution of resources.

It is always in the fine print of a census that the more interesting details lay. The preliminary release has thrown up some other rather confusing figures. While the country is rapidly becoming more urban, with over 36 percent of the population now residing in urban areas as compared to 32.5 percent in 1998, the urbanisation figures for Punjab have the potential to lead to questions. Either the conventional wisdom that Punjab is the most urbanised province is wrong or there is something that has gone wrong in the methodology used to differentiate between urban and rural areas in the census. The census reports that Sindh is 52 percent urbanised compared to 37 percent urban area in Punjab. Conjoined with the declaration that Islamabad’s urban population has decreased from 67 percent to almost 50 percent since the last census, the problem is more likely to have been one of how areas have been designated into rural and urban categories. Similarly, while it is positive to see that the number of transgender people in the country has finally been counted, at just over 10,000 the number seems extremely deflated. It is easy to ignore marginalised populations in census processes – especially in the case of a group that has not been included before.

We must also remember that the census was made into an unnecessarily complicated task. Some of it due to genuine security concerns, but mostly because of political wrangling. The Pakistan Bureau of Statistics did not receive the required funds in time and continued to remain confused about whether it would go ahead or not. That said, the results will allow for planning to be grounded in a statistical understanding of Pakistani society. However, it is important to ensure that the results have been tabulated correctly. Any issues in methodology that need to be clarified should be before the final results are announced. In the months to come, far more detailed information will be released about the population breakdown and give us a better idea of whether there has been any improvement in literacy rates, infant mortality and other vital metrics. For now, as a macro picture of the country, we have a better – if not ideal – picture of how Pakistan has changed and expanded over the last two decades.

-

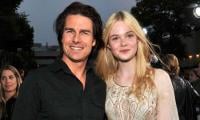

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards

Tom Cruise's Reunion With Elle Fanning Thrilled Him At Saturn Awards -

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer

Jennifer Runyon's 'Charles In Charge' Co-star Pays Tribute After She Loses Battle To Cancer -

Paul Bettany Gets Honest About Voldemort Casting Rumours In 'Harry Potter' Series

Paul Bettany Gets Honest About Voldemort Casting Rumours In 'Harry Potter' Series -

Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner Show Support As Brody Jenner Reveals Big News

Kim Kardashian, Kylie Jenner Show Support As Brody Jenner Reveals Big News -

King Charles Plans Emotional Reunion With Lilibet, Archie

King Charles Plans Emotional Reunion With Lilibet, Archie -

Royal Expert Shares Exciting Update For Princess Eugenie, Beatrice

Royal Expert Shares Exciting Update For Princess Eugenie, Beatrice -

Epstein Files: New Photos Of Former Prince Andrew With Woman On His Lap Emerge

Epstein Files: New Photos Of Former Prince Andrew With Woman On His Lap Emerge -

WhatsApp Hacked: Russia-backed Group Breaches Accounts Of Journalists, Officials, Military Personnel

WhatsApp Hacked: Russia-backed Group Breaches Accounts Of Journalists, Officials, Military Personnel -

Selena Gomez Pays Sweet Tribute To Benny Blanco On His Birthday: 'I Love You'

Selena Gomez Pays Sweet Tribute To Benny Blanco On His Birthday: 'I Love You' -

Doja Cat Calls Out Timothée Chalamet For Making Insensitive Comment About Opera

Doja Cat Calls Out Timothée Chalamet For Making Insensitive Comment About Opera -

Stephanie Buttermore's Final Heartbreaking Remarks About Fiance Jeff Nippard

Stephanie Buttermore's Final Heartbreaking Remarks About Fiance Jeff Nippard -

From Signals To Surveillance: How WiFi Tracks Human Activity Through Walls

From Signals To Surveillance: How WiFi Tracks Human Activity Through Walls -

Find Out If Your Personal Information Is Being Sold Online

Find Out If Your Personal Information Is Being Sold Online -

TCS Unveils Physical AI Innovation At 7th Gemini Experience Center In Michigan

TCS Unveils Physical AI Innovation At 7th Gemini Experience Center In Michigan -

How Well Can AI Build Android Apps? Google Aims To Find Out

How Well Can AI Build Android Apps? Google Aims To Find Out -

Tim Cook Opens Up About Apple’s Secret Formula

Tim Cook Opens Up About Apple’s Secret Formula