The caretakers are better

It has been a quiet period under the caretaker government. No dramas, no brash claims, no heated accusations and, surprisingly, a rupee appreciation against the dollar.

Pakistan’s economy is however still reeling from the gross mismanagement of the past three decades and is in a precarious position since the burden of both internal and external debt restricts the government’s ability to spend on much needed social sector and development programmes.

The quiet period is now ending as Nawaz Sharif has returned after four years to what may be another spell as prime minister in the near future. If Sharif cobbles together a parliamentary majority in any future election with the help of those he often invoked in his past speeches, then we are destined to have Ishaq Dar as finance minister again.

This time around, the former finance minister claims to have a formula to end inflation. But he has made it quite clear that the economy will take years to limp back to normal – a humility that was absent the last time he served in the government under Shehbaz Sharif with abysmal results. Let’s wait and see what the new elixir for economic revival is going to be. But nobody should hold their breath either.

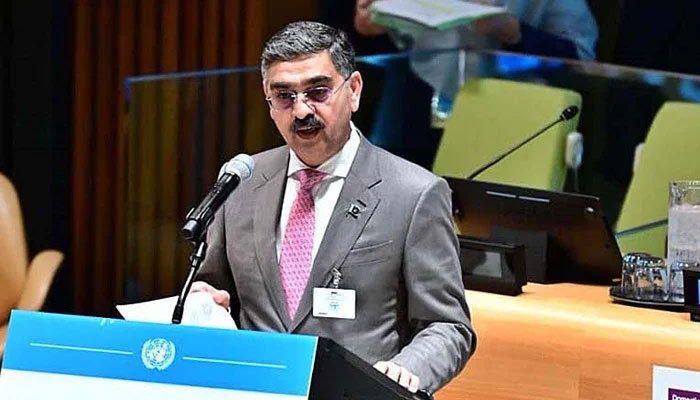

In general, Anwaar ul Haq Kakar has been an inspired pick as prime minister. He is earnest and articulate and wants to leave a positive legacy when his term ends. There are moments, however, when he projects the aura of a professor who has wandered into the wrong lecture hall but insists on delivering the lecture regardless of the fact that it is not his subject area of expertise. Hence his digression into matters of foreign policy that would be best left to his highly seasoned foreign minister. Fortunately we are seeing less of these impromptu remarks from him lately.

The economy is certainly not out of trouble even though we have some relief for the foreign exchange value of the rupee that was previously in a free fall against the dollar. The conundrum is that a stronger rupee means a current account deficit build up given that our economy is so import dependent.

With the interest expense on government debt projected to be around Rs8 trillion in the current fiscal year – about the same as the government’s tax collections without taking into account any of the other budgetary expenditure items – the government is faced with the prospect of a massive fiscal deficit of over 7.0 per cent of GDP which is going to be a breach of its commitment to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Financing the deficit through issuance of more government debt for the commercial banks to absorb would add to the already great inflationary pressures and lead to further crowding out of private sector borrowing for investment purposes. The irony is that in an attempt to dampen inflation by increasing interest rates the authorities end up exacerbating it, a case of the dog chasing its tail.

Right now the country’s banks are the major creditors of the government. As the World Bank points out in its recent assessment of Pakistan’s public expenditure, “In July 2022, more than 70 percent of all bank credit was extended to the public sector, reflecting a deep sovereign-financial sector nexus. Therefore, the health of the financial sector has become intertwined with the financial health of the government, heightening financial sector risks in the event of a severe fiscal shock”.

What this means is that if the government declares, in extremis, to declare a moratorium on debt repayments to banks because other alternatives such as printing money are untenable on the grounds that this is likely to generate hyperinflation, then banks and their depositors can be expected to take a ‘haircut’. Commercial banks with a heavy concentration of government debt could also fail.

To allay any fears about bank runs, the State Bank of Pakistan recently came out with a statement indicating that individual deposits under Rs500,000 were protected under the Deposit Guarantee Scheme. However as far as deposits over Rs500,000 are concerned, they skirted around the matter by indicating that since all the country’s banks are well capitalized and comply with internationally recognized capital adequacy rules deposits of over Rs500,000 are also secure.

Government paper denominated in rupees is supposedly safe from default. But what if the government cannot raise the domestic revenues to repay its debt and decides unilaterally to cut back or defer its repayment on domestic debt for reasons of restoring fiscal stability? This scenario is not inconceivable which is why tax revenues as a percentage of GDP have to be ramped up quickly and significantly if such drastic measures are to be avoided.

One issue with the State Bank’s inflation fighting model is the undue reliance on interest rates as a tool to fight inflation. According to economic theory, when demand pull inflation is the issue then high interest rates (along with fiscal measures) tend to cool demand side pressures through reducing uptake of home mortgages that cause asset price inflation and build-up of credit card debt by consumers. They also strengthen the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market that also helps curb inflationary pressures. Also, consumers are incentivized to cut back their spending and save more of their incomes.

However, in Pakistan’s case relying on interest rates is misdirected because our inflation is driven by supply side factors such as the floods that occurred last year and the spike in international food prices due to the war in Ukraine. High rates of indirect taxes also add to price pressures. However, the Pakistani home mortgage market is in the nascent stage and only a small fraction of the population is using credit cards. So these demand side factors are minor factors at best in driving the country’s inflation rate.

Because high interest rates can exacerbate supply chain issues and reduce investment in productive capacity, they can restrict the availability of goods and services in the short term, adding further to inflationary spikes and cause significant unemployment as factories shut down.

High interest rates can also stifle the economy’s economic growth rate as many investment projects are not viable when interest rates exceed a certain threshold and therefore discourage long-term additions to the capital stock by the private sector and to the economy’s future productive potential.

As far as strengthening the exchange rate is concerned, this is also unlikely to happen. Since our foreign currency reserves of about $8 billion can barely cover only two months of imports, any short-term investor will be chary about bringing money into the country in response to higher interest rates since they would lack confidence in the possibility of repatriating their funds freely and at a time of their choosing.

Indeed, the bigger point is that there is no single model in economics that is applicable in all circumstances. As economist Dani Rodrik of Harvard University underscores in his wonderful little book on the methodology of economics, ‘Economics Rules’, there is no universal model in economics but different models for different economic contexts.

The current level of interest rates is also unsustainable on fiscal grounds. By the government’s own estimate, a 1.0 per cent hike in interest rates adds a massive Rs300 billion to the annual domestic debt servicing requirement.

Because of the above considerations, there is an urgent need to reduce interest rates at the earliest.

The writer is a group director at the Jang Group. He can be reached at: iqbal.hussain@janggroup.com.pk

-

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash

Winter Olympics 2026: Lindsey Vonn’s Olympic Comeback Ends In Devastating Downhill Crash -

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl'

Adrien Brody Opens Up About His Football Fandom Amid '2026 Super Bowl' -

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed

Barbra Streisand's Obsession With Cloning Revealed -

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender?

What Did Olivia Colman Tell Her Husband About Her Gender? -

'We Were Deceived': Noam Chomsky's Wife Regrets Epstein Association

'We Were Deceived': Noam Chomsky's Wife Regrets Epstein Association -

Patriots' WAGs Slam Cardi B Amid Plans For Super Bowl Party: She Is 'attention-seeker'

Patriots' WAGs Slam Cardi B Amid Plans For Super Bowl Party: She Is 'attention-seeker' -

Martha Stewart On Surviving Rigorous Times Amid Upcoming Memoir Release

Martha Stewart On Surviving Rigorous Times Amid Upcoming Memoir Release -

Prince Harry Seen As Crucial To Monarchy’s Future Amid Andrew, Fergie Scandal

Prince Harry Seen As Crucial To Monarchy’s Future Amid Andrew, Fergie Scandal -

Chris Robinson Spills The Beans On His, Kate Hudson's Son's Career Ambitions

Chris Robinson Spills The Beans On His, Kate Hudson's Son's Career Ambitions -

18-month Old On Life-saving Medication Returned To ICE Detention

18-month Old On Life-saving Medication Returned To ICE Detention -

Major Hollywood Stars Descend On 2026 Super Bowl's Exclusive Party

Major Hollywood Stars Descend On 2026 Super Bowl's Exclusive Party -

Cardi B Says THIS About Bad Bunny's Grammy Statement

Cardi B Says THIS About Bad Bunny's Grammy Statement -

Sarah Ferguson's Silence A 'weakness Or Strategy'

Sarah Ferguson's Silence A 'weakness Or Strategy' -

Garrett Morris Raves About His '2 Broke Girls' Co-star Jennifer Coolidge

Garrett Morris Raves About His '2 Broke Girls' Co-star Jennifer Coolidge -

Winter Olympics 2026: When & Where To Watch The Iconic Ice Dance ?

Winter Olympics 2026: When & Where To Watch The Iconic Ice Dance ? -

Melissa Joan Hart Reflects On Social Challenges As A Child Actor

Melissa Joan Hart Reflects On Social Challenges As A Child Actor