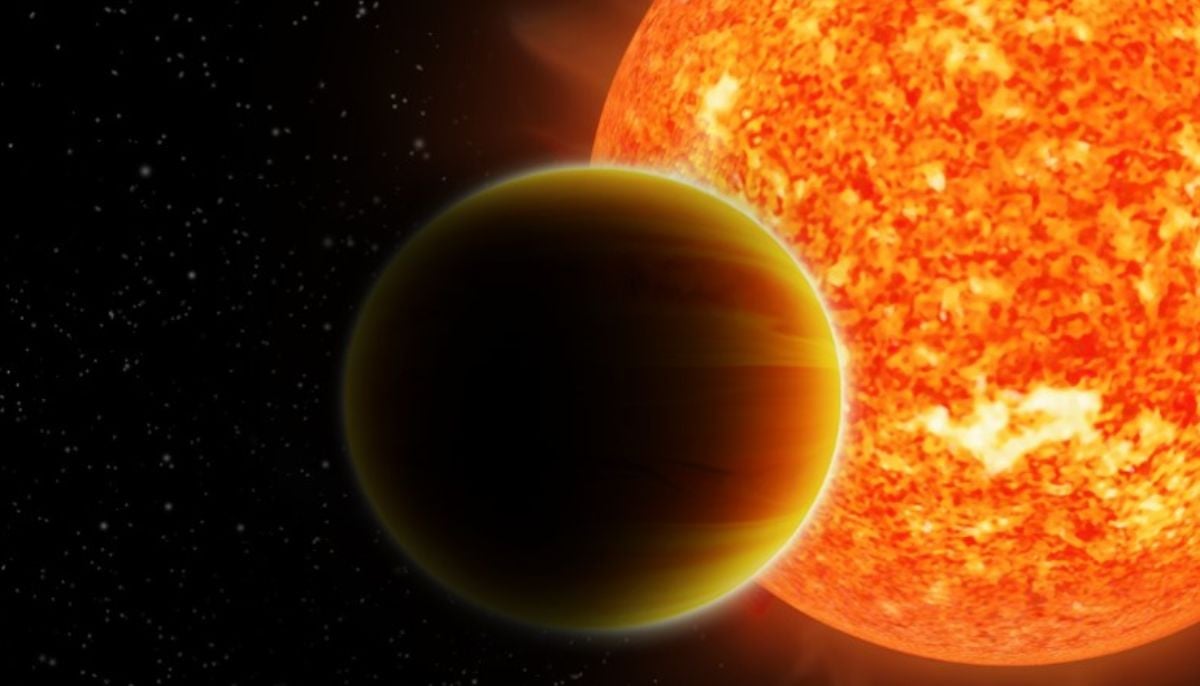

Scientists reveal how 'hot Jupiter' are really formed

In cosmic research, team of scientists studied ‘hot Jupiters’—the behavior of exoplanets in our planetary system

We know Jupiter is the largest planet in our solar system, but we rarely observed or heard about ‘Hot Jupiter’, that are giant gaseous exoplanets that are much closer to the stars and their mysteriously decaying orbits around which they revolve.

A new orbital clue reveals the method which unveils how hot Jupiter are really formed and slipped inward peacefully than being violently scattered.

Scientists observed that hot Jupiter were once cosmic oddities but how they moved so close to their stars has remained a stubborn mystery.

The hot Jupiter is the first exoplanet confirmed in 1995-a giant world similar in mass to Jupiter but orbiting its stars only for a few days.

Astronomers have identified over 4000 exoplanets but the science behind their orbital decay was still unknown.

However, scientists now think that these planets originally formed far from their host stars.

According to Science Daily, a new approach from researchers in Tokyo cracks this debate by using the timescale of orbital circulation as a diagnostic clue.

Gravitational tides and magnetic fields decide the course of the decay

In the migration scenario, a planet first follows a highly stretched path before its orbit becomes circular again as it repeatedly swings close to its star.

Researchers discovered that the time needed for a planet’s orbit to circularize can expose which path it took and the amount of time needed for this circularization depends on several factors, including the planet's mass, orbital characteristics, and tidal forces.

A number of these planets are also part of multi-planet systems, a configuration that high-eccentricity migration typically disrupts since that process can scatter or eject neighboring planets.

The University of Tokyo researchers uncovered two leading theories that explain the mechanisms involved in hot Jupiter migration: gravitational scattering caused by other planets and dynamical interactions with the still-present circumstellar disk.

The new study found that ‘Hot Jupiter’ might have arrived near their stars through either turbulent gravitational encounters or slow, steady drift.

For getting more clarity, the team introduced a new method that focuses on the length of time required for high-eccentricity migration to occur.

“It opens a new avenue of tidal research and will help guide observational astronomers in finding promising targets to observe orbital decay,” said Dr. Craig Duguid, one of the study authors and a postdoc research associate at Durham University.

During their study, the researchers discovered that a star’s magnetic field plays an important role in shaping the gravitational tides that cause the orbital decay of a hot Jupiter.

The new study by University of Tokyo researchers, published in the Journal Identifying Close-in Jupiters that arrived via Disk Migration, Evidence of Primordial Alignment,Preferrence of Nearby Companions and Hint of Runaway Migration, reflects upon the importance of how the migration is essential for piercing together the history of planetary systems.

Scientists inform that future studies may offer deeper insight into the origins and evolution of hot Jupiters.

-

Massive 600-kg NASA satellite to hit Earth Today: Could humans be at risk?

-

Massive 3D map exposes early universe like never before

-

Scientists reveal stunning images of rare deep-sea species & corals off British Caribbean coast

-

Is the world ending? New study finds rise in apocalyptic beliefs worldwide

-

Alien contact attempts may have gone unnoticed for decades, study suggests

-

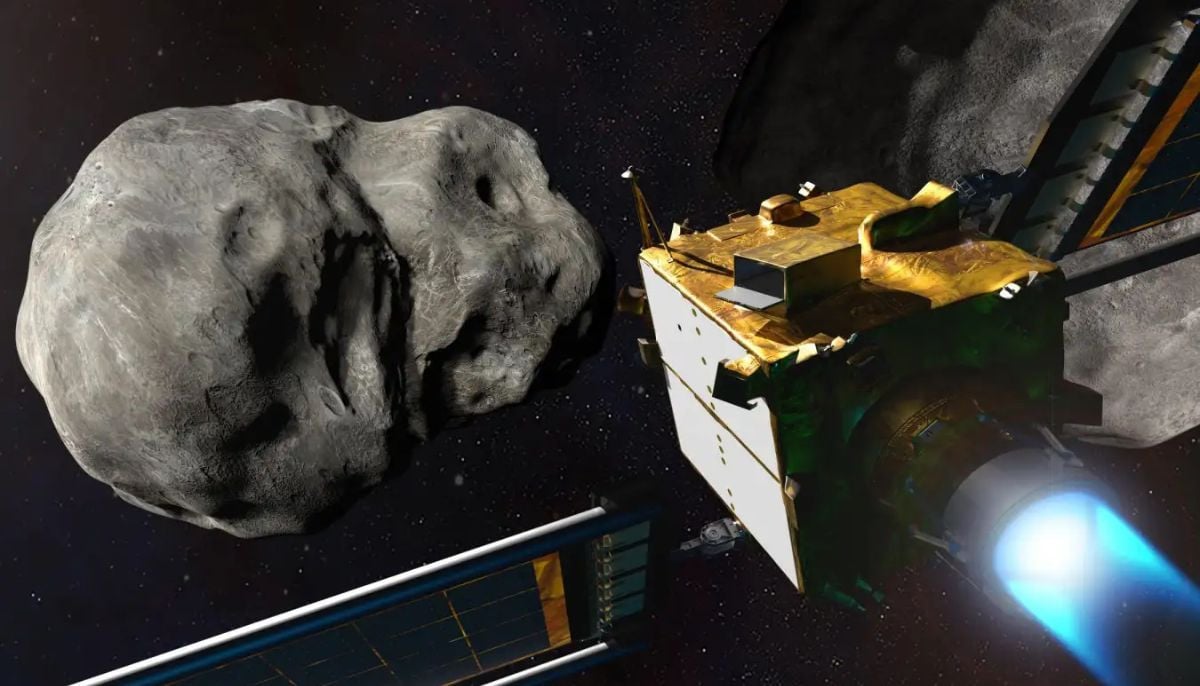

How NASA’s DART mission successfully shifted an asteroid’s orbit for planetary defense

-

NASA reveals asteroid defense breakthrough to protect Earth from killer space rocks

-

Antarctica lost ice equal to 10 times Los Angeles in 30 years, study finds