A question of authority

Legal eye

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad.

It was recently reported in this paper th

By Babar Sattar

June 15, 2013

Legal eye

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad.

It was recently reported in this paper that the federal tax ombudsman issued a warrant for the arrest of the auditor general of Pakistan. The tax ombudsman was constrained to issue the warrant, we were told, because the auditor general had the audacity to send a minion when summoned by the tax ombudsman in a contempt proceeding initiated by the latter against the former.

Going by public perceptions, Dr Shoaib Suddle, the tax ombudsman, is known to be an upright and honest police officer. He enjoys support across the political divide and is also on the right side of the Supreme Court. Most recently he was appointed as the one-man commission to investigate the Arsalan Iftikhar saga and his interim report led the honourable Supreme Court to conclude that the Arsalan Iftikhar-Malik Riaz affair was a private dispute between two parties and hardly a matter of public interest. Buland Akhtar Rana, the auditor general, on the other hand hardly enjoys a flattering reputation.

When Rana was appointed to this coveted constitutional post, the media went berserk. That he was the senior-most officer of the Accounts Service aside, we were told that the sole reason for the appointment was Rana being a crony of Yousaf Raza Gilani. At the time the honourable chief justice had also reportedly solicited intelligence reports on Rana and then written to the President informing him of charges against Rana that the president might have overlooked in making the appointment. The oath was grudgingly administered after the president insisted that he would go with Rana despite the CJ’s reservations.

In this backdrop when you hear that the tax ombudsman (by whose virtue even the honourable Supreme Court swears by) issued a contempt notice to the auditor general (a half-Canadian half-Pakistani PPP leftover that even the honourable chief justice was constrained to chide publicly), you know instantly that the tax ombudsman must be right. Even before reading on you begin celebrating the triumph of rule of law. The fact that the tax ombudsman dispatched a police inspector to go and arrest the auditor general is only the latest manifestation that in this land of the pure, law no longer discriminates between the average Joe and the mighty.

The tax ombudsman is a statutory office created by law to rectify any injustice meted out to a person due to the maladministration of tax officials. Under the Establishment of the Office of Federal Tax Ombudsman, 2000, the jurisdiction of the office is limited to investigating allegations of maladministration against tax officials. The statute states that the tax ombudsman will be entitled to such salary and allowances as determined by the president. Amongst his powers is included the power, akin to that of the Supreme Court, to punish anyone for contempt who interferes with the work of his office or scandalises the tax ombudsman.

Getting back to the story, the auditor general’s office conducts the audit of public departments and raises audit objections in relation to the use of public funds. In this specific story, while conducting such audit of the Office of the Tax Ombudsman, the relevant audit team concluded that the tax ombudsman was not entitled under law to draw salary and allowances – that he had been enjoying – equal to that of a judge of the Supreme Court. The objection made its way up the hierarchy and was upheld by the auditor general and consequently the additional allowances of the tax ombudsman were withheld.

The tax ombudsman, however, believed that in view of a notification issued by the president he was entitled to salary and allowances equal to that of a Supreme Court judge. Nothing wrong here. Reasonable people can disagree about the meaning of a notification and its legality. But then the tax ombudsman assigned to himself the legal authority to issue commands to the auditor general in relation to his own salary. He ordered the auditor general to release the additional allowances that were suspended. When the auditor general didn’t oblige, he was slapped with a contempt notice.

When summoned, the auditor general sent an officer to explain the position of his department. The tax ombudsman was livid over the auditor general’s refusal to appear in person and explain why his (the ombudsman’s) salary and allowance had been curtailed. He then elected to punish such impertinence by issuing arrest warrants for the auditor general to ensure his personal appearance.

Let’s start with the obvious first. The foundational principle of natural justice (and common sense) is that no one ought to be a judge in his own cause. What does the tax ombudsman claiming the last word on his own salary entitlement say about his sense of propriety?

The point of law is equally obvious. The tax ombudsman is a creature of statute and can only exercise such limited authority in relation to tax maladministration as vested in his office under law. He has no discretion to assume jurisdiction in relation to any matter of his choosing. What could then have possibly possessed him to issue orders to a constitutional office-holder beyond the pale of his authority? The law also states that the tax ombudsman is the principal accounting officer of his office, which is financed by public revenue and consequently its accounts are to be audited by the auditor general.

Will the tax ombudsman issue contempt notices every time the auditor general’s office raises objections over the accounts of the former? The most benevolent explanation of this incident is that it is just a case of bloated egos and the tax ombudsman’s assumption of authority to pursue a personal interest. But could this also be the manifestation of the imperious judicial culture becoming entrenched within Pakistan under an assertive judiciary, which has begun to trickle-down even to non-adversarial adjudicatory forums such as the tax ombudsman’s office?

Is disdain for the oversight role assigned to coordinate branches of government in relation to itself and disregard for the concept of separation of powers and settled doctrines of textual interpretation reflection of this imperious culture? We have seen the registrar of the Supreme Court tell the Public Accounts Committee that it has no business asking questions about how the Supreme Court uses public money. We now have the tax ombudsman issuing contempt notices to, and warrants for the arrest of, the custodian of public funds because his office dared to think that the tax ombudsman might be drawing more salary than is his due under law.

We have seen the Supreme Court exercise the oblique suo motu power rooted in Article 184(3) of the constitution to such inexplicable extent that it is no longer possible to distinguish the province of the executive or the legislature from that of the judiciary. In view of the latest jurisprudence being produced by the court, it is safe to say that the age-old conundrum about what is it that the judges do – whether they make law or interpret it – has been settled once and for all in Pakistan. The Supreme Court is the new super-executive and super-legislator apart from being the apex adjudicator and has a no-holds-barred approach to the authority it claims.

We have had the apex court rule, without any existing statutory basis, that the appointment of the chairman of NAB be made in consultation with the pater familias. In its latest judgement rightly declaring large-scale transfers made by the caretaker government illegal, the court has also elected to legislate how senior-most executive appointments must be made by a high-powered commission and prescribe the terms of reference of such commission. We have seen our high courts take suo motu notice of events when the constitution affords them no such power.

Will thoughtful judicial minds please pause to ponder over whether such imperiousness will aid or hurt rule of law in Pakistan?

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad.

It was recently reported in this paper that the federal tax ombudsman issued a warrant for the arrest of the auditor general of Pakistan. The tax ombudsman was constrained to issue the warrant, we were told, because the auditor general had the audacity to send a minion when summoned by the tax ombudsman in a contempt proceeding initiated by the latter against the former.

Going by public perceptions, Dr Shoaib Suddle, the tax ombudsman, is known to be an upright and honest police officer. He enjoys support across the political divide and is also on the right side of the Supreme Court. Most recently he was appointed as the one-man commission to investigate the Arsalan Iftikhar saga and his interim report led the honourable Supreme Court to conclude that the Arsalan Iftikhar-Malik Riaz affair was a private dispute between two parties and hardly a matter of public interest. Buland Akhtar Rana, the auditor general, on the other hand hardly enjoys a flattering reputation.

When Rana was appointed to this coveted constitutional post, the media went berserk. That he was the senior-most officer of the Accounts Service aside, we were told that the sole reason for the appointment was Rana being a crony of Yousaf Raza Gilani. At the time the honourable chief justice had also reportedly solicited intelligence reports on Rana and then written to the President informing him of charges against Rana that the president might have overlooked in making the appointment. The oath was grudgingly administered after the president insisted that he would go with Rana despite the CJ’s reservations.

In this backdrop when you hear that the tax ombudsman (by whose virtue even the honourable Supreme Court swears by) issued a contempt notice to the auditor general (a half-Canadian half-Pakistani PPP leftover that even the honourable chief justice was constrained to chide publicly), you know instantly that the tax ombudsman must be right. Even before reading on you begin celebrating the triumph of rule of law. The fact that the tax ombudsman dispatched a police inspector to go and arrest the auditor general is only the latest manifestation that in this land of the pure, law no longer discriminates between the average Joe and the mighty.

The tax ombudsman is a statutory office created by law to rectify any injustice meted out to a person due to the maladministration of tax officials. Under the Establishment of the Office of Federal Tax Ombudsman, 2000, the jurisdiction of the office is limited to investigating allegations of maladministration against tax officials. The statute states that the tax ombudsman will be entitled to such salary and allowances as determined by the president. Amongst his powers is included the power, akin to that of the Supreme Court, to punish anyone for contempt who interferes with the work of his office or scandalises the tax ombudsman.

Getting back to the story, the auditor general’s office conducts the audit of public departments and raises audit objections in relation to the use of public funds. In this specific story, while conducting such audit of the Office of the Tax Ombudsman, the relevant audit team concluded that the tax ombudsman was not entitled under law to draw salary and allowances – that he had been enjoying – equal to that of a judge of the Supreme Court. The objection made its way up the hierarchy and was upheld by the auditor general and consequently the additional allowances of the tax ombudsman were withheld.

The tax ombudsman, however, believed that in view of a notification issued by the president he was entitled to salary and allowances equal to that of a Supreme Court judge. Nothing wrong here. Reasonable people can disagree about the meaning of a notification and its legality. But then the tax ombudsman assigned to himself the legal authority to issue commands to the auditor general in relation to his own salary. He ordered the auditor general to release the additional allowances that were suspended. When the auditor general didn’t oblige, he was slapped with a contempt notice.

When summoned, the auditor general sent an officer to explain the position of his department. The tax ombudsman was livid over the auditor general’s refusal to appear in person and explain why his (the ombudsman’s) salary and allowance had been curtailed. He then elected to punish such impertinence by issuing arrest warrants for the auditor general to ensure his personal appearance.

Let’s start with the obvious first. The foundational principle of natural justice (and common sense) is that no one ought to be a judge in his own cause. What does the tax ombudsman claiming the last word on his own salary entitlement say about his sense of propriety?

The point of law is equally obvious. The tax ombudsman is a creature of statute and can only exercise such limited authority in relation to tax maladministration as vested in his office under law. He has no discretion to assume jurisdiction in relation to any matter of his choosing. What could then have possibly possessed him to issue orders to a constitutional office-holder beyond the pale of his authority? The law also states that the tax ombudsman is the principal accounting officer of his office, which is financed by public revenue and consequently its accounts are to be audited by the auditor general.

Will the tax ombudsman issue contempt notices every time the auditor general’s office raises objections over the accounts of the former? The most benevolent explanation of this incident is that it is just a case of bloated egos and the tax ombudsman’s assumption of authority to pursue a personal interest. But could this also be the manifestation of the imperious judicial culture becoming entrenched within Pakistan under an assertive judiciary, which has begun to trickle-down even to non-adversarial adjudicatory forums such as the tax ombudsman’s office?

Is disdain for the oversight role assigned to coordinate branches of government in relation to itself and disregard for the concept of separation of powers and settled doctrines of textual interpretation reflection of this imperious culture? We have seen the registrar of the Supreme Court tell the Public Accounts Committee that it has no business asking questions about how the Supreme Court uses public money. We now have the tax ombudsman issuing contempt notices to, and warrants for the arrest of, the custodian of public funds because his office dared to think that the tax ombudsman might be drawing more salary than is his due under law.

We have seen the Supreme Court exercise the oblique suo motu power rooted in Article 184(3) of the constitution to such inexplicable extent that it is no longer possible to distinguish the province of the executive or the legislature from that of the judiciary. In view of the latest jurisprudence being produced by the court, it is safe to say that the age-old conundrum about what is it that the judges do – whether they make law or interpret it – has been settled once and for all in Pakistan. The Supreme Court is the new super-executive and super-legislator apart from being the apex adjudicator and has a no-holds-barred approach to the authority it claims.

We have had the apex court rule, without any existing statutory basis, that the appointment of the chairman of NAB be made in consultation with the pater familias. In its latest judgement rightly declaring large-scale transfers made by the caretaker government illegal, the court has also elected to legislate how senior-most executive appointments must be made by a high-powered commission and prescribe the terms of reference of such commission. We have seen our high courts take suo motu notice of events when the constitution affords them no such power.

Will thoughtful judicial minds please pause to ponder over whether such imperiousness will aid or hurt rule of law in Pakistan?

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

-

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis

Nick Jonas Gets Candid About His Type 1 Diabetes Diagnosis -

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign

King Charles Sees Environmental Documentary As Defining Project Of His Reign -

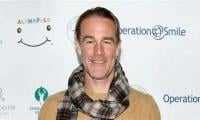

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death

James Van Der Beek Asked Fans To Pay Attention To THIS Symptom Before His Death -

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s

Portugal Joins European Wave Of Social Media Bans For Under-16s -

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared'

Margaret Qualley Recalls Early Days Of Acting Career: 'I Was Scared' -

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients

Sir Jackie Stewart’s Son Advocates For Dementia Patients -

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries

Google Docs Rolls Out Gemini Powered Audio Summaries -

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting

Breaking: 2 Dead Several Injured In South Carolina State University Shooting -

China Debuts World’s First AI-powered Earth Observation Satellite For Smart Cities

China Debuts World’s First AI-powered Earth Observation Satellite For Smart Cities -

Royal Family Desperate To Push Andrew As Far Away As Possible: Expert

Royal Family Desperate To Push Andrew As Far Away As Possible: Expert -

Cruz Beckham Releases New Romantic Track 'For Your Love'

Cruz Beckham Releases New Romantic Track 'For Your Love' -

5 Celebrities You Didn't Know Have Experienced Depression

5 Celebrities You Didn't Know Have Experienced Depression -

Trump Considers Scaling Back Trade Levies On Steel, Aluminium In Response To Rising Costs

Trump Considers Scaling Back Trade Levies On Steel, Aluminium In Response To Rising Costs -

Claude AI Shutdown Simulation Sparks Fresh AI Safety Concerns

Claude AI Shutdown Simulation Sparks Fresh AI Safety Concerns -

King Charles Vows Not To Let Andrew Scandal Overshadow His Special Project

King Charles Vows Not To Let Andrew Scandal Overshadow His Special Project -

Spotify Says Its Best Engineers No Longer Write Code As AI Takes Over

Spotify Says Its Best Engineers No Longer Write Code As AI Takes Over