Inadequate testing thwarts efforts to measure Zika's impact

The World Health Organization says as many as 4 million people could become infected across the Americas and that Zika has already been locally transmitted in at least 30 countries. But a true measure of the outbreak and its implications is impossible until doctors can quickly and reliably identify Zika through serology, a common test of blood contents that measures antibodies triggered in the immune system by a given infection.

RIO DE JANEIRO: One major hurdle is thwarting efforts to measure the extent of the Zika epidemic and its suspected links to thousands of birth defects in Brazil: accurate diagnosis of a virus that still confounds blood tests.

Genetic tests and clinical symptoms have enabled scientists to partially track Zika, and Brazil guesses up to 1.5 million people have been infected in the country.

The World Health Organization says as many as 4 million people could become infected across the Americas and that Zika has already been locally transmitted in at least 30 countries.

But a true measure of the outbreak and its implications is impossible until doctors can quickly and reliably identify Zika through serology, a common test of blood contents that measures antibodies triggered in the immune system by a given infection.

Laboratories in Brazil, the United States and elsewhere are rushing to develop serology tests that can accurately identify Zika antibodies while ignoring those triggered by other related viruses with similar structures. For years, the similarities have confused serology research.

Brazil's government, desperate for tests to deploy at clinics and hospitals across the continent-sized country, hopes such a test could be developed in months. Many researchers are skeptical.

"The likelihood of this happening soon is close to zero," says Robert Lanciotti, chief of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's diagnostics laboratory in Fort Collins, Colorado. "It is a long-standing problem that many people have been unable to solve even with cutting-edge molecular biology."

At stake is knowing just who may have carried an infection that does not even show symptoms in four out of five people who get it. Even for those that do get the aches, mild fever and rash most associated with Zika, the symptoms can easily be confused with those of other tropical maladies.

Sure diagnoses would also enable scientists to better understand suspected links to microcephaly, a condition marked by abnormally small head size that can result in development problems.

Brazilian officials believe Zika may be associated with more than 4,000 suspected cases of microcephaly since October. Researchers have identified evidence of Zika infection in 17 cases, either in the baby or in the mother, but have not confirmed that Zika can cause microcephaly

The lack of clear diagnoses is part of the reason that the number of confirmed links between Zika and microcephaly lags so far behind the number of those suspected.

"The testing available now is very limiting because we need to know far more about who actually had this infection to be able to research the virus and its complications," says Claudia Nunes dos Santos, a researcher on Zika serology and the director of molecular virology at a lab operated by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, a prominent government health institute, in Curitiba, in southern Brazil.

-

Late James Van Der Beek inspires bowel cancer awareness post death

-

Bella Hadid talks about suffering from Lyme disease

-

Gwyneth Paltrow discusses ‘bizarre’ ways of dealing with chronic illness

-

Halsey explains ‘bittersweet’ endometriosis diagnosis

-

NHS warning to staff on ‘discouraging first cousin marriage’: Is it medically justified?

-

Ariana Grande opens up about ‘dark’ PTSD experience

-

Dakota Johnson reveals smoking habits, the leading cause of lung cancer

-

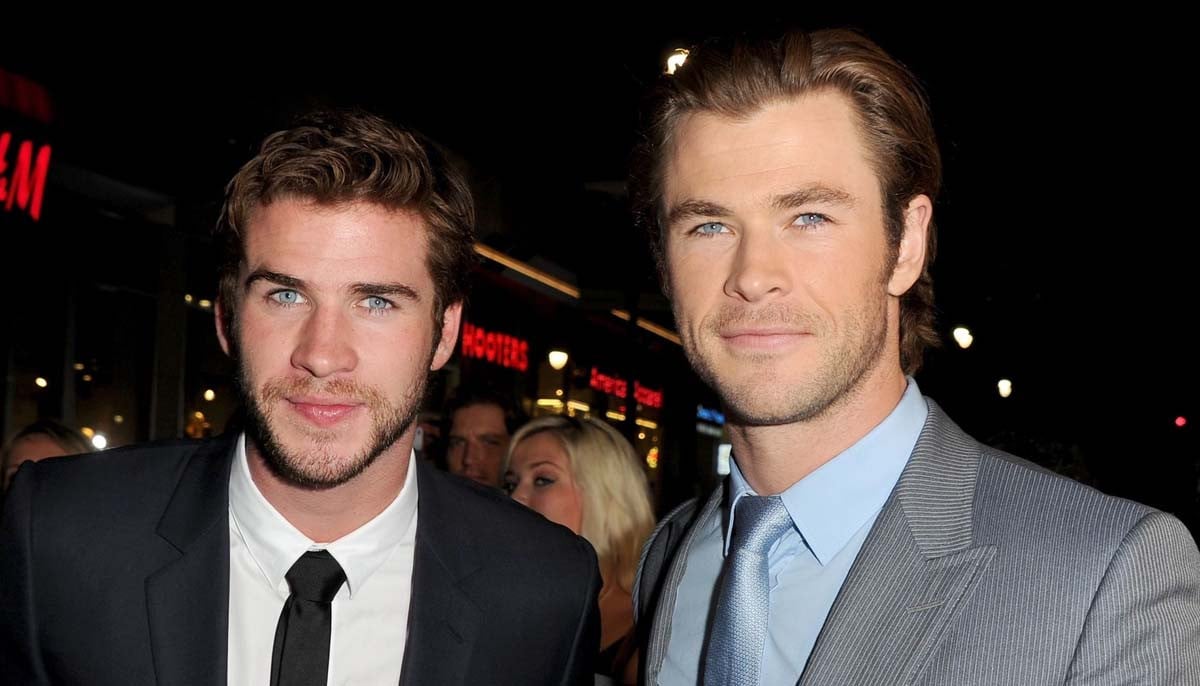

Chris, Liam Hemsworth support their father post Alzheimer’s diagnosis