Translation of Muhammad Siddique Musafir’s book brings to fore traumatic experiences of Sheedi community

The history of the Sheedi community might by an interesting story for others but for the people of the community, it was a plethora of traumatic tales of slavery, repression and discrimination that did not allow them to prosper.

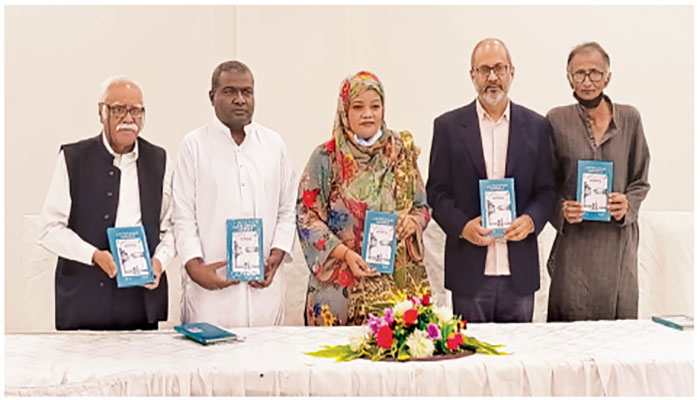

Tanzila Qambrani, the first Sheedi woman who became a member of the Sindh Assembly in 2018 on the Pakistan Peoples Party’s ticket, made this remark as she addressed the recent launch of an Urdu translation of famed educationist and writer Muhammad Siddique Musafir’s (1879 -1961) account of the Sheedi community at the Arts Council of Pakistan.

The translation, titled ‘Ghulami Aur Azadi Kay Ibratnaak Nazarey — Zindabad Azadi’, has been done by noted researcher Aslam Khwaja from Sindhi into Urdu.

Haris Gazdar, senior researcher at the Collective for Social Science Research, Karachi; Iqra Qambrani, research scholar from the Sheedi community; and Iqbal Haider Sheedi, a Badin-based community activist, also spoke on the book at the event that was moderated by academic and journalist Dr Tausif Ahmed Khan.

Speakers said the Sheedi community faced widespread discrimination in Pakistan from other community groups due to their appearance and colour, especially in social matters such as marriage and education.

Tanzila said Musafir was a real hero who taught many members of the Sheedi community to live a respectable life. She added that both of her parents were his students.

Commenting on how difficult it was for the Sheedi community to share their plight, she remarked that it was easy to talk about one’s successes but it was always traumatic to describe the mistreatment one faced in their daily lives. “When we talk about the community’s issues in Tando Bago, Karachi or a United Nations forum, we talk about pain and grief.”

She said the community had struggled hard to prove itself equal to others but even after centuries, they were still being subjected to humiliation. “Education is our way out of poverty,” she said as she described prejudice that many Sheedi children were still facing at schools.

In his talk, Gazdar cited his field research trip of a town of Balochistan where residents said there was no caste discrimination. “But when I visited the school and checked the student’ enrolment register, ‘ghulam’ (slaves) was written in front of some children’s names.”

He said that culture and identity was born out of the people’s struggle. Praising the translator, he said such books and research work should be published on a regular basis as they help empower everyone, particularly the marginalised communities like the Sheedis.

The book

In his preface to the book, Khwaja has written that no research on Sindh’s Sheedi community has been conducted on a scientific basis. Regarding Musafir’s work, he said Musafir was born to slave parents and he compiled direct observations and experiences in his memoirs published in Sindh some five decades ago.

In the book’s introduction, Mishal Khan, a sociologist at the Center for International Social Science Research, University of Chicago, has stated that the book provides analytical insight into lives, ideologies and memories of the Sindh’s Sheedi community.

“The book is not only helpful for the researchers focusing on comparative systems of slavery, African immigrants and various aspects of movements of abolishing of slavery in various parts of the world, but it is also an invaluable treasure for the people interested in various identities in South Asia in the context of the 20th century.

Musafir’s book began with the origins of the Sheedis, a community in Pakistan who are the descendants of East Africans brought to the area as slaves by Arab and Egyptian merchants over several centuries. The first chapter of the book discusses the historical context of slavery of the Sheedi community and the second chapter is about the history of various Black freedom movements initiated by leaders of the community in various parts of the world.

The third chapter of the book discusses the struggle of African-Americans. In the fourth chapter, the author describes the stories of various slaves who were brought to Sindh by their masters. Musafir wrote that most of the Sheedis in Sindh were slaves of wealthy people but a significant number of them were also kept by Baloch tribesmen, Syeds and Pirs (spiritual figures). According to the author, Hindu masters of the Sheedi slaves were comparatively more merciful.

The fifth chapter discusses the situation of Sheedis in Sindh after the British abolished slavery in 1843 by declaring keeping slaves and their trade a crime. Although the Sheedis were no longer slaves after that, their problems did not perish as the community had to face poverty, illiteracy and disunity.

In the book’s second part, Musafir described his own experiences and observations. The author’s father was sold at the age of seven in a slave market in Zanzibar to an Arab trader of Muscat. He was later sold to a sculptor in Thatta. He narrates how his father, after the abolition of slavery, started his new life and formed an organisation of Habshis of Tando Bago.

-

Giant Tortoise Reintroduced To Island After Almost 200 Years

Giant Tortoise Reintroduced To Island After Almost 200 Years -

Eric Dane Drops Raw Confession For Rebecca Gayheart In Final Interview

Eric Dane Drops Raw Confession For Rebecca Gayheart In Final Interview -

Trump Announces New 10% Global Tariff After Supreme Court Setback

Trump Announces New 10% Global Tariff After Supreme Court Setback -

Influencer Dies Days After Plastic Surgery: Are Cosmetic Procedures Really Safe?

Influencer Dies Days After Plastic Surgery: Are Cosmetic Procedures Really Safe? -

Eric Dane Confesses Heartbreaking Regret About Daughters' Weddings Before Death

Eric Dane Confesses Heartbreaking Regret About Daughters' Weddings Before Death -

Nicole 'Snooki' Polizzi Reveals Stage 1 Cervical Cancer Diagnosis

Nicole 'Snooki' Polizzi Reveals Stage 1 Cervical Cancer Diagnosis -

Hilary Duff’s Son Roasts Her Outfit In New Album Interview

Hilary Duff’s Son Roasts Her Outfit In New Album Interview -

Alexandra Daddario, Andrew Form Part Ways After 3 Years Of Marriage

Alexandra Daddario, Andrew Form Part Ways After 3 Years Of Marriage -

Eric Dane Rejected Sex Symbol Label

Eric Dane Rejected Sex Symbol Label -

Avan Jogia Says Life With Fiancee Halsey Feels Like 'coming Home'

Avan Jogia Says Life With Fiancee Halsey Feels Like 'coming Home' -

Kate Middleton's Role In Handling Prince William And Harry Feud Revealed

Kate Middleton's Role In Handling Prince William And Harry Feud Revealed -

Tucker Carlson Says Passport Seized, Staff Member Questioned At Israel Airport

Tucker Carlson Says Passport Seized, Staff Member Questioned At Israel Airport -

David, Victoria Beckham Gushes Over 'fiercely Loyal' Son Cruz On Special Day

David, Victoria Beckham Gushes Over 'fiercely Loyal' Son Cruz On Special Day -

Taylor Swift Made Sure Jodie Turner-Smith's Little Girl Had A Special Day On 'Opalite' Music Video Set

Taylor Swift Made Sure Jodie Turner-Smith's Little Girl Had A Special Day On 'Opalite' Music Video Set -

Eric Dane Says Touching Goodbye To Daughters Billie And Georgia In New Netflix Documentary

Eric Dane Says Touching Goodbye To Daughters Billie And Georgia In New Netflix Documentary -

Channing Tatum Reveals What He Told Daughter After Violent Incident At School

Channing Tatum Reveals What He Told Daughter After Violent Incident At School