China’s edge?

Though the 21st century was predicted to be the Chinese century, nobody knew the nature and trajectory of Beijing's rise.

The aggressive Chinese attitude during the border dispute with India in the Galwan river valley has heralded Beijing's arrival. Not just India, but the entire world was astounded by China's belligerent response.

The geopolitical events unfolding in the aftermath of the Covid-19 outbreak compelled Beijing to (re)assert itself more forcefully. Though the India-China border dispute will eventually deescalate, what has transpired during the border crisis has unmistaken implications for the balance of power in South Asia.

Exploiting the US retreat from South Asia and India's troubled ties with its neighbours, Beijing has expanded its political and economic influence on New Delhi's detriment. India has considered South Asia as its sphere of influence after the departure of the British Raj in 1947. But this may have changed after the China-India standoff in the Himalayan region.

One of the reasons behind the increasing Chinese influence in South Asia is India’s strained ties with most of its neighbours. In his second term, Prime Minister Modi’s "neighborhood first policy" lies in the doldrums. In 2019, India almost went to war with Pakistan and following the unilateral revocation of Kashmir's special status in August last year, the relations nosedived further.

Similarly, ties with Nepal are at all-time low after the 2015 blockade and the recently approved map by the Nepalese parliament that includes land claimed by Delhi. Likewise, the Bangladesh-India relations have been frosty since the Citizen Amendment Act was implemented in Assam and Amit Shah termed Bangladeshi migrant workers in India as termites. India's two historic allies, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are drifting towards China as well. Delhi's influence in Afghanistan also remains uncertain ahead of the expected US withdrawal.

Bereft of India's bullying attitude, the smaller South Asian nations could not resist the lucrative Chinese lucrative Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Partnership with China offers smaller South Asia nations three distinct advantages. First, an alternative option and bargaining power against India. Second, China is viewed as a reliable partner by the smaller South Asian countries at the international diplomatic forums. Third, the inclusion in the BRI gives the South Asian political elites big-ticket infrastructure development projects to strengthen their political constituencies.

South Asia is one of the least economically integrated regions in the world. Due to border disputes, mistrust and security concerns, the intraregional trade is well below the real potential in South Asia. Most of the South Asian states rely on developed nations for exports, and China for imports.

The negligibly low intraregional trade and India's decision to weaken the already fragile South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Saarc) to wish away Pakistan paved the way for the Chinese economic ingress. There were no real commercial interests at stake for the smaller South Asia states before opting for the BRI. In South Asia, the BRI may replace the dormant Saarc as the new regional economic integration model.

Notwithstanding its image as a rising global power, economic powerhouse and a close US ally, Beijing saw through New Delhi's bluff and eventually called it by militarily confronting it in the Himalayan region. During the Pulwama-Balakot crisis, Pakistan blunted India by shooting down its plane in the dogfight and catching the pilot. This projection-reality gap was not lost on the Chinese during the standoff in the Galwan valley.

Another critical factor of Chinese success and the Indian failure is of their soft power perception in the calculations of smaller South Asian states. Due to its bullying attitude, Delhi comes across as an aggressor and expansionist power, while Beijing, given its non-intrusive approach, is viewed as a reliable security and economic partner.

In recent years, the US’s reputation as a coalition partner has been dented globally. The muted US reaction to Iran-supported drone attacks on the Saudi oil refinery, Aramco, the abandonment of the Syrian Kurds through unilateral withdrawal from Syria, warning to the Afghan government to talk to the Taliban or face aid cuts and acting as a mere bystander in the India-China border dispute has left a lot to be desired.

The US retreat from South Asia as the primary security guarantor and interlocutor left a yawning leadership vacuum which is now being filled by China. Washington’s silence on the Delhi-Beijing border standoff is deafening.

In retrospect, the US absence was particularly felt during the Pulwama-Balakot crisis between India and Pakistan. Instead of urging both sides to act with restraint and de-escalate, Washington temporarily paused, supporting Delhi's so-called right to self-defence before activating the backchannel. The belated US intervention and partisanship eroded American influence and reliability as a security partner, forcing smaller states like Pakistan to rethink their future options to balance India.

Once the India-China tensions de-escalate, the smaller South Asian nations will have to walk a tightrope to balance their relations between the two rival powers. They will most likely adopt a hedging strategy to continue their engagements with China without unnecessarily antagonizing India. In this intricate pattern of bilateral and multilateral relations, cooperation and competition will go hand in hand. Unlike the cold-war era politics, where states were in the capitalist or communist blocks or non-aligned, the countries may cooperate in some areas and may compete in others.

Though the situation between Delhi and Beijing will normalize, it will not return to South Asia's old status quo. The New Cold war is here, and we have just seen a glimpse of how it is likely to play out in the South Asian region. Following the US presidential elections in November, the contours of this new rivalry will become more prominent.

The writer is a research fellowat the S Rajaratnam School ofInternational Studies, Singapore.

Email: isabasit@ntu.edu.sg

-

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss -

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning -

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding -

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene -

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce -

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All'

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All' -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals -

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked -

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

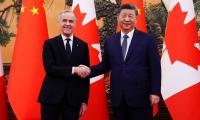

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training