Lower courts performed exceptionally in 2019, but relief to public remained elusive

Twenty-eight-year-old Peter, real name Pervez Iqbal, works as a barber in Gulistan-e-Jauhar. His slender frame stands five feet and eight inches tall. His curly hair, untrimmed patchy beard and deep-set eyes make him look like a mystic. And his attire reflects affection for the hip-hop culture.

Even though he’s an early school dropout, he has very good knowledge of the criminal justice system, thanks to his bitter experience with the police and the courts.

One Saturday night in the middle of 2019, he was picked up by the Rangers during a raid at a snooker club in Hussain Hazara Goth and later handed over to the police.

The Mubina Town police booked him in a case of possessing illegal weapons along with two other people whom he didn’t know at that time. He was released six months later, but only after his family had incurred expenses of around Rs100,000 on the legal process.

Sharing his ordeal with The News, he said that despite being innocent, he had to prove it with the help of a lawyer in court. He said he would earn the money back, but there was no replacing the time that was wasted.

“Also, now I carry a stigma with me. People don’t say it to your face, but behind your back they wonder, ‘He must have done something, which is why he was taken away’.”

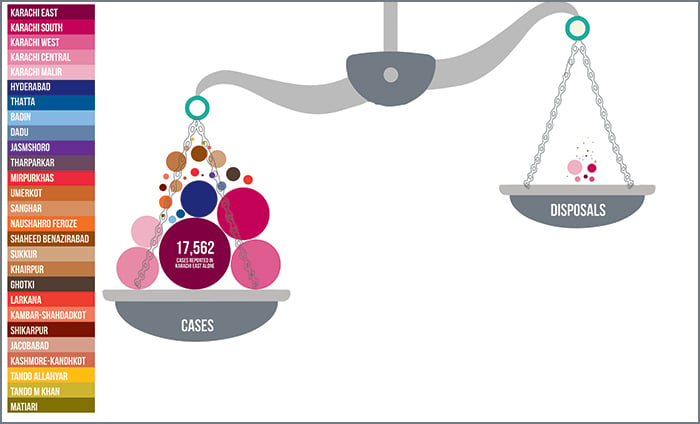

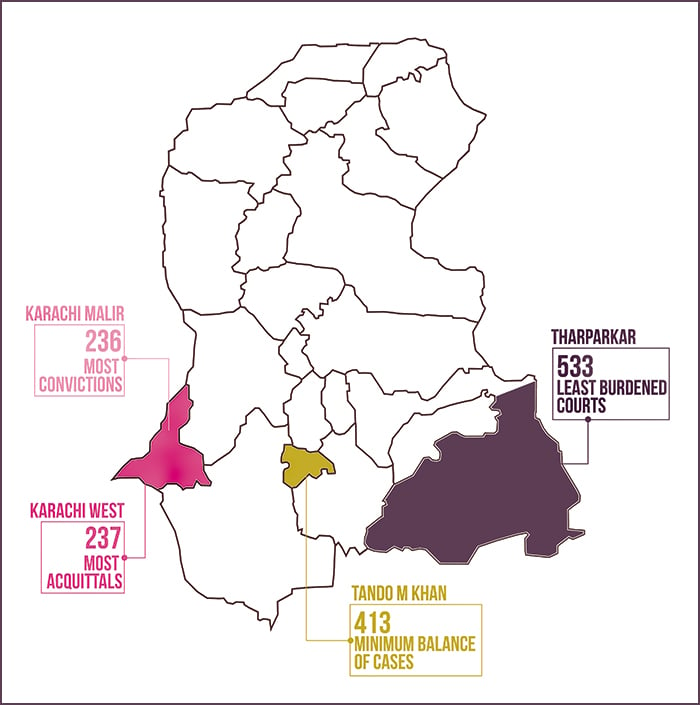

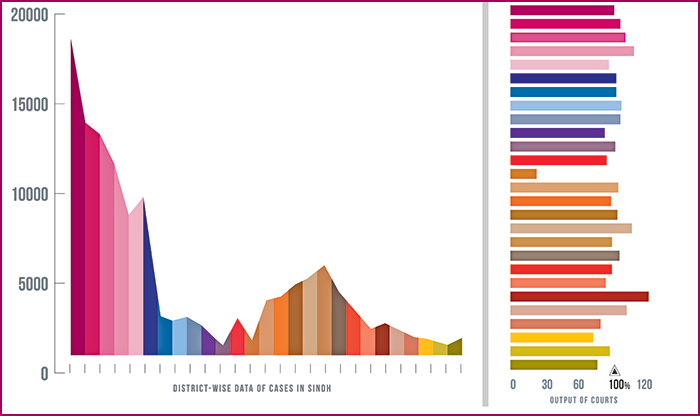

An analysis of the data of Sindh’s district judiciary suggests that the courts are doing exceptionally well, giving an output of up to 97 per cent, only if we consider the ratio of institutions of cases to disposal of cases over a period of 12 months ending in November 2019.

But when we take into account the backlog of cases still plaguing the lower courts, it tells an entirely different story. Nonetheless, even their exceptional performance doesn’t seem to reflect in relief to the public.

Let’s look at another case: Sofia Yousuf is a Malaysian national who had married a Pakistani man in 2015. Two years later, she gave birth to a boy.

The couple didn’t get along, and in March 2018, the husband lodged a complaint with the police that his wife had run away from their house with their child, cash and jewellery. He nominated two people for luring her into running away.

During the investigation, the police found that the allegations were false and submitted a C-class (lack of evidence) report, which the court approved and quashed the case. The husband then moved another application seeking the child’s custody, but the court ruled in favour of Sofia on January 2, 2020.

Then there’s the case of banker Zainab*. In 2018, when the fake accounts cases started to emerge, she was one of the first persons to be summoned by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) for questioning.

Her world turned upside down. Newly married and expecting her first child, she found herself entangled in legal matters, because as an employee her job was to open accounts, including the one which forwarded to her by the bank president himself.

She was working at another bank when she was summoned. Soon after that happened, she was asked to resign. The HR department told her she could apply again after her role in the investigation ended. A banking court in Karachi was hearing her case then.

The police were already at her home, despite the fact that she had been granted bail by the court, to acquire which the family had had to submit the documents of their home.

Frustrated with the circumstances, the couple headed to Islamabad to see the then chief justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar, who heard them and ordered the FIA director general to ensure that she got her job back. Finally, she was back at the office.

The couple are now parents to two children, but the case is still under way in Rawalpindi, for which they travel whenever she is summoned by the court.

Despite all these hardships, Zainab has faith in the judicial system. She told The News that though the court granted her relief, it wasn’t soon enough. “The time that has been wasted is irreplaceable.”

In another recent case, journalist Nasrullah Chaudhry was sentenced to five years in jail by an anti-terrorism court (ATC) on December 26, 2019 for possessing radical literature and having links with proscribed organisations. His appeal against the conviction is pending with the Sindh High Court (SHC).

His attorney Muhammad Farooq said that a person who is implicated in a false case can seek compensation for the damages caused to him, and under the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) a judge can also punish the police for their faulty investigation, but this doesn’t actually happen.

“People usually don’t want to get involved with the courts again.”

The parties involved in the above-mentioned cases had to go through a painstaking process, but they were able to pass through the primary level of the judicial system in a relatively good time, between six to 18 months.

Otherwise they would have been among the unfortunate ones — 88 per cent of the litigants — in Sindh who still wait for the day when their cases would be decided.

Courts of law

Back in March 2019, former SHC judge Mujeebullah Siddiqui had said during a talk in Karachi that “the courts are courts of law and not of justice. They must do justice in accordance with the law. Otherwise there is no difference between a court and a Jirga”.

Muhammad Khan Buriro, an ATC judge who recently resigned citing “unavoidable circumstances”, commented that as soon as a trial begins, the judge gets an idea whether the accused is guilty or falsely implicated. “From there the judge can pick up the pace and decide the case asap.”

Buriro pointed out that although the ATA stipulates that courts decide a matter within seven days of its cognisance, there is no such instruction for the district & sessions courts, where most of the litigations take place.

“We need to formulate a special law and take special measures to solve the problems that the courts are facing,” he said. He lamented that many of the 95,000 plus pending cases may never get decided because the lower courts don’t have enough resources.

“But the government can, if it wants to, induct more people in courts, uphold merit and give benefits to judges and staff members. Motivate them, and they’ll do the work.”

*Name changed to protect privacy

-

2026 Winter Olympics Men Figure Skating: Malinin Eyes Quadruple Axel, After Banned Backflip

2026 Winter Olympics Men Figure Skating: Malinin Eyes Quadruple Axel, After Banned Backflip -

Meghan Markle Rallies Behind Brooklyn Beckham Amid Explosive Family Drama

Meghan Markle Rallies Behind Brooklyn Beckham Amid Explosive Family Drama -

Scientists Find Strange Solar System That Breaks Planet Formation Rules

Scientists Find Strange Solar System That Breaks Planet Formation Rules -

Backstreet Boys Voice Desire To Headline 2027's Super Bowl Halftime Show

Backstreet Boys Voice Desire To Headline 2027's Super Bowl Halftime Show -

OpenAI Accuses China’s DeepSeek Of Replicating US Models To Train Its AI

OpenAI Accuses China’s DeepSeek Of Replicating US Models To Train Its AI -

Woman Calls Press ‘vultures’ Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Home After Tense Standoff

Woman Calls Press ‘vultures’ Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Home After Tense Standoff -

Allison Holker Gets Engaged To Adam Edmunds After Two Years Of Dating

Allison Holker Gets Engaged To Adam Edmunds After Two Years Of Dating -

Prince William Prioritises Monarchy’s Future Over Family Ties In Andrew Crisis

Prince William Prioritises Monarchy’s Future Over Family Ties In Andrew Crisis -

Timothée Chalamet Turns Head On The 'show With Good Lighting'

Timothée Chalamet Turns Head On The 'show With Good Lighting' -

Bucks Vs Thunder: Nikola Topic Makes NBA Debut As Milwaukee Wins Big

Bucks Vs Thunder: Nikola Topic Makes NBA Debut As Milwaukee Wins Big -

King Charles Breaks 'never Complain, Never Explain' Rule Over Andrew's £12 Million Problem

King Charles Breaks 'never Complain, Never Explain' Rule Over Andrew's £12 Million Problem -

Casey Wasserman To Remain LA Olympics Chair Despite Ghislaine Maxwell Ties

Casey Wasserman To Remain LA Olympics Chair Despite Ghislaine Maxwell Ties -

Shaun White Is Back At The Olympics But Not Competing: Here’s Why

Shaun White Is Back At The Olympics But Not Competing: Here’s Why -

Breezy Johnson Engaged At Olympics After Emotional Finish Line Proposal

Breezy Johnson Engaged At Olympics After Emotional Finish Line Proposal -

King Charles Wants Andrew To 'draw A Line' Under Epstein Issue

King Charles Wants Andrew To 'draw A Line' Under Epstein Issue -

John Wick Game Confirmed With Keanu Reeves And Lionsgate Collaboration

John Wick Game Confirmed With Keanu Reeves And Lionsgate Collaboration