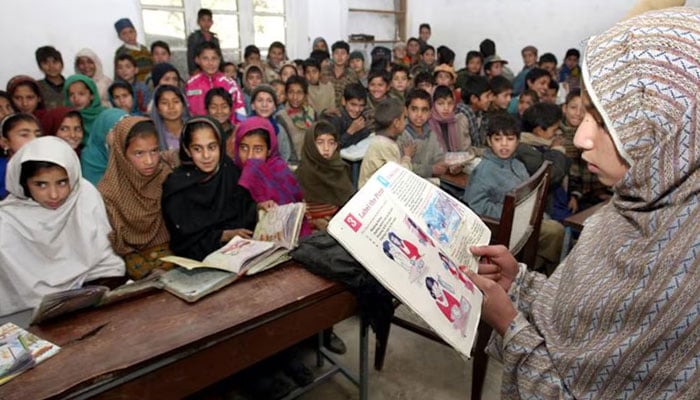

Country of ‘first boys’: education disparities: Part – I

Despite differences and recent challenges to democracy, India has made substantial progress in many areas

The ‘country of first boys’ can offer different possibilities to boys from favoured backgrounds, which contrast sharply with the meagre opportunities that girls from underprivileged families get, writes Indian Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen.

What is true for India is more than true for Pakistan. Despite caste and class differences and recent challenges to democracy, India has made substantial progress in many areas. On the contrary, our social, economic, and political systems are stagnant and have impeded progress for decades.

‘First boys’ from elite families in Pakistan get good schooling, better nutrition and health services. They inherit money and power; are trained differently to become part of the country’s power machine; and move abroad using family connections and networks to capitalize not necessarily on meritocracy but on the strength, abilities and confidence come through the unequal systemic bias that favours them.

In contrast, ‘last girls’ – girls from underprivileged groups – when their gender identity interfaces with class, religion and geography do not enjoy these freedoms; face economic hardships; are forced to follow the age-old social traditions that worsen the level of deprivation; and have no say in political decision-making. The denial of equal opportunities leads to a bleak future for not only them but also the country.

The segregated education system ensures that few among the pool of young people get privileged education. The systemic economic and social disparities related to geography at birth, gender and class determine who is picked up and who is left out.

The social and economic status at birth decides the lifetime outcomes. ‘First boys’ reap the best benefits while last boys and particularly ‘last girls’ cannot even read and write.

Let us look at a few numbers to substantiate the argument about how class- and gender-biased our education system is and what kind of results it is producing.

In the year 2018-19, around 92 per cent of men in the top 20 per cent households – based on their consumption spending – from the urban areas of Pakistan were found to be literate while only 20 per cent of women from the bottom-fifth households from rural areas are literate. What this tells us is that if you are a woman from rural areas and fall into the lower income group, your chances of being literate are 4.5 times lower than the urban male from the top income group.

In addition to the differences between urban men in the top 20 per cent income group and rural women in the bottom 20 per cent, there is also a gap between urban women in the top 20 per cent and the bottom 20 per cent. For example, 83 per cent women in the top 20 per cent households in urban areas of Pakistan are literate, compared to only 34 per cent women in the bottom-fifth income group in urban areas. Similarly, 63 per cent women in the top 20 per cent households in rural areas are literate compared to 20 per cent women in the bottom fifth in the region.

The situation is even grimmer if we unpack these aggregate national numbers. For example, according to 2018-19 figures, only 7.0 per cent of rural women from the bottom-fifth households in Balochistan; 12 per cent in Sindh; 24 per cent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP); and 28 per cent in Punjab are literate. There is a wide disparity among provinces when compared to the national average of female literacy in rural areas among different income groups.

There is also a large literacy gap among women from the top 20 per cent of households in Punjab and those in Balochistan. Sixty-seven per cent of rural and 84 per cent urban women from the top 20 per cent of households in Punjab are literate, while only 49 per cent of rural and 69 per cent urban women in Balochistan from the same income group are literate.

There is also a wide educational inequality within provinces. For example, in the best performing province – Punjab – 92 per cent of urban men from the top 20 per cent households are literate, while only 28 per cent of rural women from the bottom-fifth are literate. Similarly, in Sindh, 93 per cent of urban men from the top 20 per cent households are literate, while only 12 per cent of rural women from the bottom-fifth are literate. The situation in KP and Balochistan is also not different.

A deep dive into district-level education statistics further reveals the stark realities of wasted talent and equality opportunities. Ninety-one per cent men and 80 per cent women from urban areas of Islamabad are literate while this percentage for rural Islamabad is 89 per cent and 78 per cent respectively. However, if compared with a low-performing district in Punjab’s Rajanpur, only 51 per cent rural men and 21 per cent rural women are literate.

In Sindh, the top five districts are in Karachi. Korangi is on top, where 87 per cent men and 80 per cent women are literate. Similarly, in Karachi East, 86 per cent and 77 per cent women are literate. If compared with Tharparkar, only 65 per cent urban men and 38 per cent women are literate, while this percentage in rural Tharparkar is 41 per cent and 12 per cent respectively for men and women. So, urban women in Karachi have seven times more chances of getting an education in comparison to rural women in Tharparkar.

The worrying fact is that there is slow progress on filling this gap and tapping the potential of ‘last boys and girls’. In 2018-19, 30 per cent of children aged 5-16 were out of school – 36 per cent girls and 25 per cent boys. In the 2004-05 and 2019-20 periods, the net enrolment rate of girls at the primary level increased only 12 per cent – from 48 per cent to 60 per cent – or 1.0 per cent a year. With this rate, it will take 40 years to achieve 100 per cent national net enrolments of women at the primary level.

The national average masks stark disparities among provinces for net primary enrolment for women from 2004-5 to 2019-20. KP has been on top, increasing girls primary net enrolment from 40 per cent to 59 per cent from 2004-5 to 2019-20 (19 per cent increase with an average of 1.6 per cent per year), while the low performer is Sindh, achieving only a 7.0 per cent increase in the net enrolment rate (from 42 per cent to 49 per cent) in 12 years – 0.6 per cent annually.

It will take about 70 years in Sindh to achieve the 100 per cent primary net enrolment rate at the current pace. And this is only about net primary enrolment, let alone secondary-level education (matric) or a university degree. This means that when Pakistan will be 100 years old in 2047, the dream of teaching our girls to read and write will still be unfulfilled, what to talk of providing them with quality and decent higher education opportunities.

To be continued

The writer is an Islamabad-based environmental and human rights activist.

-

James Van Der Beek's Friends Helped Fund Ranch Purchase Before His Death At 48

James Van Der Beek's Friends Helped Fund Ranch Purchase Before His Death At 48 -

King Charles ‘very Much’ Wants Andrew To Testify At US Congress

King Charles ‘very Much’ Wants Andrew To Testify At US Congress -

Rosie O’Donnell Secretly Returned To US To Test Safety

Rosie O’Donnell Secretly Returned To US To Test Safety -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Spotted On Date Night On Valentine’s Day

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Spotted On Date Night On Valentine’s Day -

King Charles Butler Spills Valentine’s Day Dinner Blunders

King Charles Butler Spills Valentine’s Day Dinner Blunders -

Brooklyn Beckham Hits Back At Gordon Ramsay With Subtle Move Over Remark On His Personal Life

Brooklyn Beckham Hits Back At Gordon Ramsay With Subtle Move Over Remark On His Personal Life -

Meghan Markle Showcases Princess Lilibet Face On Valentine’s Day

Meghan Markle Showcases Princess Lilibet Face On Valentine’s Day -

Harry Styles Opens Up About Isolation After One Direction Split

Harry Styles Opens Up About Isolation After One Direction Split -

Shamed Andrew Was ‘face To Face’ With Epstein Files, Mocked For Lying

Shamed Andrew Was ‘face To Face’ With Epstein Files, Mocked For Lying -

Kanye West Projected To Explode Music Charts With 'Bully' After He Apologized Over Antisemitism

Kanye West Projected To Explode Music Charts With 'Bully' After He Apologized Over Antisemitism -

Leighton Meester Reflects On How Valentine’s Day Feels Like Now

Leighton Meester Reflects On How Valentine’s Day Feels Like Now -

Sarah Ferguson ‘won’t Let Go Without A Fight’ After Royal Exile

Sarah Ferguson ‘won’t Let Go Without A Fight’ After Royal Exile -

Adam Sandler Makes Brutal Confession: 'I Do Not Love Comedy First'

Adam Sandler Makes Brutal Confession: 'I Do Not Love Comedy First' -

'Harry Potter' Star Rupert Grint Shares Where He Stands Politically

'Harry Potter' Star Rupert Grint Shares Where He Stands Politically -

Drama Outside Nancy Guthrie's Home Unfolds Described As 'circus'

Drama Outside Nancy Guthrie's Home Unfolds Described As 'circus' -

Marco Rubio Sends Message Of Unity To Europe

Marco Rubio Sends Message Of Unity To Europe