Time for a change

India's upcoming elections, starting April 19 and stretching until June 1, are certainly world’s largest exercise in voting

Before the latest round of BJP rule under the iron fist of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi began in 2014, the consensus opinion was that India is South Asia’s best democracy and arguably the best in the Global South as a whole.

Its upcoming elections, slated to begin on April 19 and stretching until June 1, are certainly the world’s largest exercise in voting, with around 960 million registered voters. And then there is also the fact that elected governments have held sway in India, more or less uninterrupted, since it won its independence in 1947.

When this unbroken democratic streak is contrasted with the spotty track record of India’s neighbours and much of the rest of the developing world, one can understand the fanfare. But this was pre-PM Modi, pre-religious minorities being disenfranchised and barred from citizenship and having their freedom restricted, pre-the region's freest press, on paper, being muzzled by a combination of private money and public power, pre-state violence against peaceful protesters and pre-opposition leaders being picked up on corruption charges and rival parties having their bank accounts frozen to the point that they complain of being unable to campaign. It is not as though these things never happened in India pre-Modi, but they have certainly been kicked up a notch under his rule.

Last week, Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal became the second opposition chief minister to be arrested on corruption charges this year. A popular opposition leader being arrested for corruption in an election year? Did someone say Pakistan? The party workers protesting CM Kejriwal's arrest were hit with the same iron fist as the farmers marching peacefully for their rights and the people of Occupied Kashmir speaking out against their illegal annexation. ‘If you cannot win them over, crush them’ appears to have become the BJP motto when it comes to dissent. All this has, to a great extent, silenced the Indian democracy chorus, with some openly asking if it is indeed dead.

This would imply that PM Modi and the BJP are the killers. Indeed, much of the fretting about India’s democratic backsliding often centres almost entirely around what the current government is doing. Rescuing Indian democracy and secularism thus becomes about removing one man and one party. Sadly, this is not the case. The Hindutva phenomenon ought to prompt a deeper look at the structural flaws rooted in Indian democracy. After all, PM Modi and BJP did not seize power in a coup. They are an outcome of India’s democracy. And no, Hindutva is not a bug in an otherwise good system leading to undesirable results. This style of oppressive majoritarianism is arguably a feature of the system

The first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all style of parliamentary democracy in India is part of a very long list of British things that former British colonies should have thrown out with British rule but have kept around to their detriment. The system favours majority rule, even when a party does not even command a majority of votes. The BJP-led NDA coalition has won less than 40 per cent of votes in India’s last two elections, winning just around 31 per cent of votes in 2014. And yet, its rule is virtually uncontested. One does not need a lot of votes in this system, just enough votes in a lot of places will do. Religious majoritarianism is simply the best response to first-past-the-post in India, a religiously diverse country but with Hindus making up the majority in most places. Why put in the effort of cobbling together a multi-religious, pluralistic coalition when simply appealing to one group will do the trick?

A broad, inclusive coalition makes sense when one is trying to get rid of a colonial oppressor that thrives on divide-and-conquer. Sticking to a strategy that has outlived its purpose can arguably explain the contrasting fortunes of the BJP and Congress to a great extent. Nor is keeping a colourful coalition together easy. It requires compromise both from the majority and the minority. Those who fail this balancing act risk upsetting both. The BJP is unencumbered by such dynamics. Even though there are many Hindus who reject its bigoted ideology, enough are willing to go along for it to win parliament and rule unopposed.

Apologists for India’s authoritarian turn might argue that harping on about rights and secularism is all well and good but the imperative to get things done is just as, if not more, important. A system that distributes power more equally might also be less decisive in exercising it, too constrained by the imperative to balance competing needs. After all, India has supplanted its former colonial masters as the world’s fourth largest economy under the BJP, its education system is churning out CEO after CEO of some of the most valuable companies in the world and it has even reached the moon. But these milestones, though impressive, can be deceptive.

To a great extent, the BJP has been in the right place at the right time and is lucky to be running a big country with low expectations. Poverty is still widespread in India, with a GDP per capita lower than Bangladesh’s and less than $1000 per year higher than Pakistan’s. As per the World Bank, over 10 per cent of India’s population still has to defecate in the open while, as of 2021, around three-quarters of its population was reportedly unable to afford a healthy diet. The Congress government that preceded the BJP managed to attain similar growth rates while avoiding entirely the negative growth PM Modi’s government clocked during Covid-19, while bungling the response to the pandemic as well. But India is bigger than most and thus can climb high on global rankings that only take the aggregate into account, giving bragging rights to a country where most have little to cheer about.

This does not mean that the narrative of India’s success is all a myth. Just that its governance under the BJP has not been as an increasingly vocal, often non-resident Indian lobby would claim. Thus, for the good of abstract rights, principles, and material outcomes, perhaps it is time to try something different.

The writer is an assistant editor at The News. He tweets/posts

@SubhaniSami and can be reached at: samisubhani85@gmail.com

-

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame

Dwayne Johnson Confesses What Secretly Scares Him More Than Fame -

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus

Elizabeth Hurley's Son Damian Breaks Silence On Mom’s Romance With Billy Ray Cyrus -

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’

Shamed Andrew Should Be Happy ‘he Is Only In For Sharing Information’ -

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter

Daniel Radcliffe Wants Son To See Him As Just Dad, Not Harry Potter -

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud

Apple Sued Over 'child Sexual Abuse' Material Stored Or Shared On ICloud -

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels

Nancy Guthrie Kidnapped With 'blessings' Of Drug Cartels -

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing

Hailey Bieber Reveals Justin Bieber's Hit Song Baby Jack Is Already Singing -

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras -

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards -

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest -

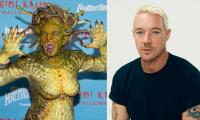

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween'

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween' -

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down -

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest?

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest? -

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights -

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed