Analysis: Mastering the roster; a statistical study

As Master of the Roster, they exercise unbridled discretion to select benches to hear cases

In legal theory, all judges of a court are equal. Many chief justices cite the Latin phrase ‘primus inter pares’ to claim they are only ‘first among equals’. The wisdom of the court, it is said, is a collective and collegiate wisdom and a chief justice’s judicial opinions carry no greater weight than that of any other judge.

But do chief justices practise what they preach? As Master of the Roster, they exercise unbridled discretion to select benches to hear cases. This blurs the distinction between the chief justice’s role as institutional administrator of the court and his role as a collegial member of the bench.

Do chief justices succumb to the natural desire to ensure primacy of their own opinion by employing their mastery of the roster to select benches of judges more likely to agree with them? The power risks making him or her not just ‘first among equals’, but ‘master of the bench’. And does that skew the reality of our apex court closer to the Orwellian logic – all judges are equal, but some judges are more equal than others?

The debate is not novel to Pakistan. Five years back, in India, four senior judges held a press conference against Chief Justice Dipak Mishra alleging “cases having far-reaching consequences for the nation and the institution have been assigned by the Chief Justice of this court to the benches of his preference”. It had no effect. When a petition was subsequently filed challenging the chief justice’s discretion, Mishra selected and presided over a bench that reasserted his mastery of the roster. Ironically, when one of the four rebels, Justice Gogoi himself became chief justice – he assiduously avoided any step towards reform.

Academics in India, and in jurisdictions like Canada and South Africa, have statistically scrutinized the power of chief justices to form benches and assign cases and whether they use this power strategically to reach desired ideological outcomes. For some chief justices, at least, they found the answer to be in the affirmative. Other countries avoid this problem altogether, either (like the US Supreme Court) by mandating all judges of the apex court must sit collectively or (like Philippines, Nepal and Brazil) by forming benches and assigning cases randomly.

In Pakistan, the debate has assumed political significance. Political leaders affiliated to the PDM allege there is a group of judges within the Supreme Court who share an ideological bent and important political cases, over the past few years, are almost exclusively assigned to benches comprising, or having a majority, of such judges. They have coined the term ‘like-minded judges’ to refer to them and list, as an example, almost a dozen cases thus fixed including the issue of elections in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the PTI’s right to hold a ‘long march’ to Islamabad, interpretation of Article 63-A of the constitution, the challenge to the NAB Ordinance amendments, and the inquiry into the Justice Mazahir Naqvi audio-leaks. While unfounded complaints by losing parties about allegedly biased benches are far from uncommon, these allegations have assumed greater weight for three reasons.

Firstly, because nearly all high-profile political cases heard by the apex court in the past two years have invited – with a frequency and vehemence unknown to our judicial history – a formal request from one or more litigants for constitution of “a full court”. All requests, thus far, have been denied.

Secondly, this perception regarding wrongful exercise of the power to form benches and affix cases – even if unfounded – has contributed to the passage of two separate Acts of Parliament seeking to regulate Supreme Court procedures and constitution of benches. As one erstwhile government minister, Khurram Dastagir, stated in his speech supporting the legislation, “independence of judiciary does not mean discretion of one individual”. One of those Acts has already been struck down by the Supreme Court – again, it is alleged, by a “like-minded bench”.

Thirdly, and most importantly, at least seven serving Supreme Court judges have, on different occasions, questioned the authority of the chief justice in constitution of benches and at least some of them have, vociferously, protested their persistent alleged exclusion from important constitutional cases. In his farewell speech, a recently retired judge, Justice Baqar, complained “exclusion of certain judges from the hearing of sensitive cases… has an adverse effect on the impartiality of judges while also tarnishing the public’s perception about the independence and integrity of the judiciary” and has created “fissures amongst members of the bench.”

Other judges have, however, vehemently defended the chief justice’s primacy as ‘master of the roster’ and his discretion to form benches and assign cases as he pleases, deeming it a settled constitutional issue.

Who is right? Do chief justices employ their mastery of the roster for strategic purposes? Are some judges systematically included, and others excluded, from benches to whom politically important cases are assigned? Do chief justices exhibit a bias (conscious or unconscious) in the selection of benches hearing such cases? If so, there is a compelling reason to regulate the chief justice’s discretion.

To answer these questions, we employed a statistical study of decisions of the Supreme Court from December 31, 2016 to June 30, 2023 – a period covering the entire tenures of the last three chief justices (and all but three months of the incumbent chief justice’s tenure) and compiled a data-set of all Supreme Court decisions within this period reported in the two leading law journals – PLD and SCMR. In total, there were 1957 reported decisions (excluding decisions reported more than once).

We then sought to identify ‘politically important’ decisions within this set. Of course, deciding if a particular case is politically important or not may be subjective. While impossible to eliminate subjectivity, we minimized it by defining politically important cases as a case meeting one of the following criteria:

i) Filed by or against a political party;

ii) Involving the eligibility of a politician to contest elections to or hold high political office;

iii) Relating to conduct of elections or having significant electoral implications;

iv) Relating to alleged serious misconduct of a politician including inquiries, criminal charges, bail, travel restrictions, freezing of assets etc;

v) Challenging a major legislative, policy, appointment or administrative decision of the federal and provincial governments having direct and significant political impact for the ruling party/ies;

vi) Involving an issue of major importance for the armed forces, intelligence agencies or their heads.

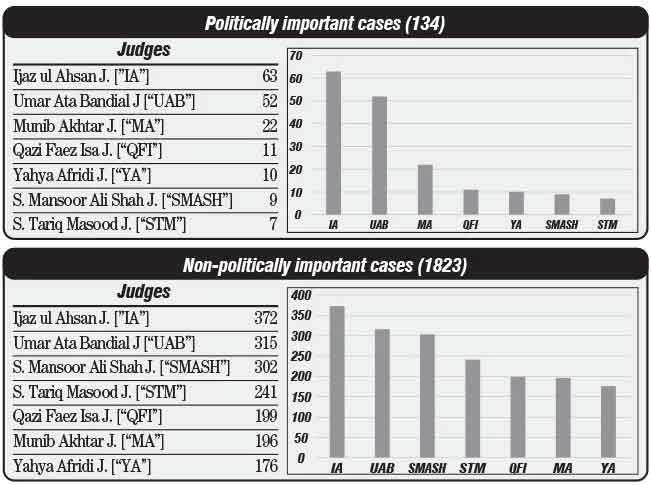

Using these criteria, we identified 134 politically important decisions in this period. We then compared the composition of benches deciding politically important cases to that of benches deciding non-politically important cases. The results shed some light on the questions posed above.

Among the seven senior judges who have been in the apex court for at least five years (a group that includes Justices Bandial, Isa, Masood, Ahsan, Shah, Akhtar and Afridi), there is a clear and statistically significant disparity when it comes to assignment of political cases.

The tables below compare the frequency with which each of those seven featured in benches deciding politically important cases and in benches deciding non-politically important cases.

In terms of featuring in non-politically important cases, all seven judges are closely clustered together. While Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan still features in the most benches, he is only 1.89 times more likely to be part of a bench deciding non-politically important cases than Justice Yahya Afridi (the last on the list).

When it comes to politically important cases, however, there is a stark disparity. Justices Ijaz ul Ahsan and Umar Ata Bandial, followed at some distance by Justice Munib Akhtar (whose rate of inclusion in such cases jumps dramatically in the present and previous chief justice’s tenures), are far more likely to be included than the other four. Indeed, when assigning politically important cases to a bench (or constituting a special bench to hear politically important cases), chief justices were fully nine-times more likely to have included Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan than Justice Sardar Tariq (the last on the list).

Clearly, then, some judges are more equal than others.

We also segregated data for the tenure of each chief justice separately. Some interesting patterns emerge. In Chief Justice Saqib Nisar’s tenure, a total of 60 politically important cases were decided. He was part of such cases 33 times while Justices Ijaz ul Ahsan and Bandial sat in on 30 and 26 occasions respectively. At the other end of the spectrum, Justice Sardar Tariq, Mansoor Ali Shah and Yahya Afridi were included a total of 3, 0 and 0 times respectively (though it must be noted the latter two were appointed in the middle of Chief Justice Nisar’s tenure).

Now chief justices, generally, are more likely (five-times more) to include themselves in benches hearing politically important cases compared to non-politically important cases. That may be unsurprising. Some chief justices, however, demonstrate clear preferences in the judges they choose to join them. So during Chief Justice Nisar’s tenure, the odds of inclusion of Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan on benches headed by the chief justice were over 10 times higher than his odds of inclusion on benches not headed by the chief justice. Similarly, during that period, the odds that Justice Bandial would be part of a bench hearing a political important case were around three-times higher than the odds of him being included in a non-politically important case.

In contrast, there are no such statistically significant correlations for Chief Justice Asif Khosa’s tenure.

We must note here that, while nearly all legally (and politically) significant decisions of general import are included in the PLD and SCMR, many (relatively insignificant) decisions of the Supreme Court are not reported and technical decisions in specific areas of law are often carried in one of the more specialized law journals. But adding those to the data set is only likely to increase the disparity noted above. While a fuller and more academic exposition of our process and conclusions must await another occasion, we share our preliminary findings for general readers here since it is clear complaints about selective formation of benches in the apex court are not entirely baseless.

To protect the institutional functioning of the court and its independence and legitimacy, the power to form benches and assign benches cannot remain at the whim of the chief justice alone. It tends to:

i) Impair public confidence in the neutrality of the apex court and its chief justice.

ii) Expose, needlessly, individual judges to accusations of bias.

iii) Breed distrust and promote fissures between judges.

iv) Limit the institutional independence of judges on a bench. If the choice to disagree with the chief justice carries the added risk of future marginalization from important cases, judges are less likely to voice their disagreement. It undermines the open and collegial deliberations that ensure the court’s decisions are a product of collective wisdom.

v) Potentially undermine the external independence of the court – since actors outside the court, seeking to influence the court’s decisions, need only co-opt one judge (the chief justice) to ensure the court’s decisions on relevant matters skew in their favour. It makes the institutional capture of Pakistan’s powerful Supreme Court much easier.

A more transparent and confidence-inspiring method of constituting benches and assigning cases is easily possible using technology and international examples. That would dispel the impression (with apologies to jurist John Selden) that justice in Pakistan varies with the size of the chief justice’s foot.

-

King Charles Holds Emergency Meeting After Andrew Arrest: 'Abdication Is Not Happening'

King Charles Holds Emergency Meeting After Andrew Arrest: 'Abdication Is Not Happening' -

Amazon Can Be Sued Over Sodium Nitrite Suicide Cases, US Court Rules

Amazon Can Be Sued Over Sodium Nitrite Suicide Cases, US Court Rules -

'Vikings' Star Mourns Eric Dane's Death

'Vikings' Star Mourns Eric Dane's Death -

Patrick Dempsey Reveals Eric Dane's Condition In Final Days Before Death

Patrick Dempsey Reveals Eric Dane's Condition In Final Days Before Death -

'Heartbroken' Nina Dobrev Mourns Death Of Eric Dane: 'He'll Be Deeply Missed'

'Heartbroken' Nina Dobrev Mourns Death Of Eric Dane: 'He'll Be Deeply Missed' -

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Arrest: What Happened When A Royal Was Last Tried?

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Arrest: What Happened When A Royal Was Last Tried? -

Alyssa Milano Expresses Grief Over Death Of 'Charmed' Co-star Eric Dane

Alyssa Milano Expresses Grief Over Death Of 'Charmed' Co-star Eric Dane -

Prince William, Kate Middleton Camp Reacts To Meghan's Friend Remarks On Harry 'secret Olive Branch'

Prince William, Kate Middleton Camp Reacts To Meghan's Friend Remarks On Harry 'secret Olive Branch' -

Daniel Radcliffe Opens Up About 'The Wizard Of Oz' Offer

Daniel Radcliffe Opens Up About 'The Wizard Of Oz' Offer -

Channing Tatum Reacts To UK's Action Against Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor

Channing Tatum Reacts To UK's Action Against Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor -

Brooke Candy Announces Divorce From Kyle England After Seven Years Of Marriage

Brooke Candy Announces Divorce From Kyle England After Seven Years Of Marriage -

Piers Morgan Makes Meaningful Plea To King Charles After Andrew Arrest

Piers Morgan Makes Meaningful Plea To King Charles After Andrew Arrest -

Sir Elton John Details Struggle With Loss Of Vision: 'I Can't See'

Sir Elton John Details Struggle With Loss Of Vision: 'I Can't See' -

Epstein Estate To Pay $35M To Victims In Major Class Action Settlement

Epstein Estate To Pay $35M To Victims In Major Class Action Settlement -

Virginia Giuffre’s Brother Speaks Directly To King Charles In An Emotional Message About Andrew

Virginia Giuffre’s Brother Speaks Directly To King Charles In An Emotional Message About Andrew -

Reddit Tests AI-powered Shopping Results In Search

Reddit Tests AI-powered Shopping Results In Search