Trump says 'US may make a deal on Cuba': What it means for Cubans?

The U.S. President Donald Trump did not offer any details about what level of outreach his administration has had with Cuba recently or when

US President Donald Trump expressed on Saturday, January 31, 2026, that the United States would "work a deal" on Cuba.

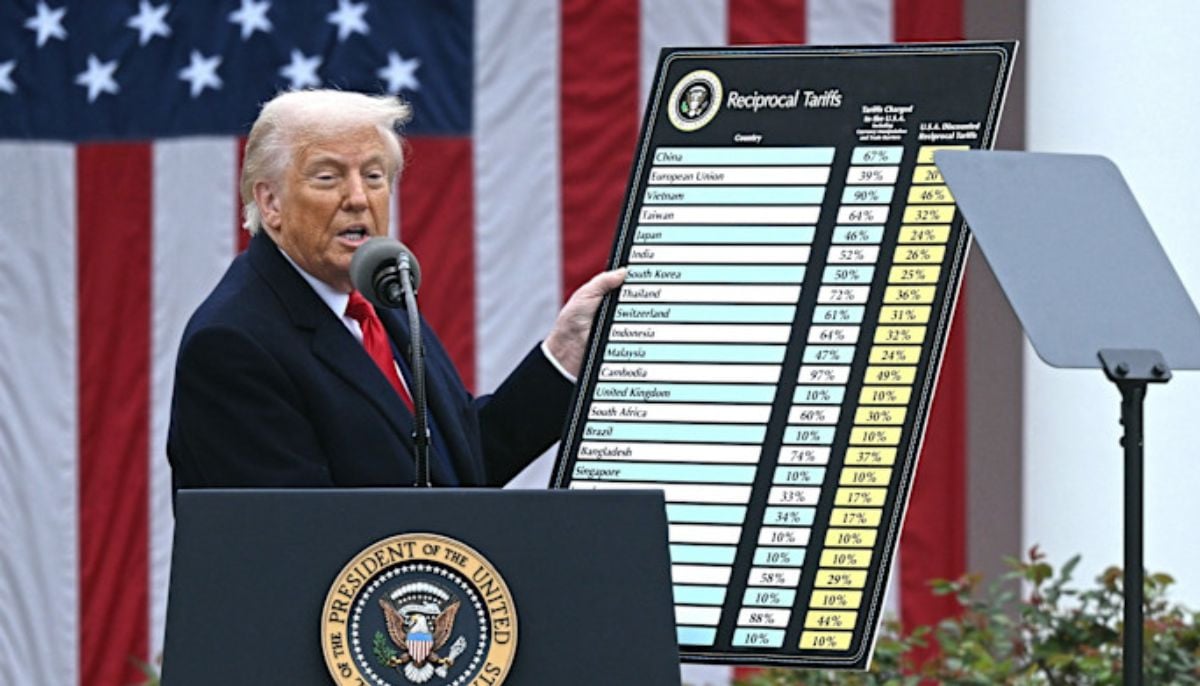

Trump reiterated his call for Cuba to negotiate with the United States. His comments came days after threatening tariffs on any country supplying Cuba with oil.

"It doesn't have to be a humanitarian crisis," Trump told reporters aboard Air Force One en route to Florida.

"I think they probably would come to us and want to make a deal... They have a situation that's very bad for Cuba. They have no money. They have no oil. They lived off Venezuelan money and oil, and none of that's coming now."

Venezuela was Cuba's largest oil supplier in 2025, meeting roughly one-third of the island's daily needs. Supply from Venezuela dropped following the US blockade on shipments from there, even before the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro.

Reuters exclusively reported in January that Mexico, Cuba's top supplier after Venezuela cut off shipments in December, was reviewing whether to continue sending oil amid fears it could face retaliation from Washington.

Cubans under siege as US Stranglehold Sets in:

Cubans from all walks of life are hunkering into survival mode, navigating lengthening blackouts and soaring prices for food, fuel and transport as the US threatens a stranglehold on the communist-run nation.

Reuters interviewed over three dozen residents of towns and neighborhoods around the capital, Havana—the country's political and economic engine—from street vendors to private sector workers, taxi drivers and state employees.

Together, those discussions paint a picture of a people pushed to the limit as goods and services—particularly those tied to ever more limited fuel supplies—become scarcer and more expensive.

For much of rural Cuba, this is not entirely new. The island's frail and antiquated power generation system has been slowly failing for years, and residents have grown accustomed to spending hours at a time without functioning electricity, internet, or water pumps.

But the seaside capital, where the streets are lined with 1950s-era cars and colorful if decrepit Spanish colonial architecture, has until recently fared better.

Now crisis looks set to swamp it, too, as fuel shortages take hold, with first Venezuela and then Mexico halting oil shipments to the island.

US President Donald Trump has said tariffs will be imposed on imports from countries that supply Cuba with oil, ratcheting up the pressure on Washington's longtime foe in the wake of the ousting of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, a key Cuban ally, in early January.

In many other countries, the conditions would have sent people out into the streets. So far, in a nation where dissent has long been curbed, there has been little sign of protest, but it is unclear how much more Cubans will be willing to endure.

Cuba's peso has lost more than 10% of its value against the dollar in three weeks, pushing up the price of groceries.

Daily life getting more difficult:

Trump, when asked about the prospect of a US military intervention in Cuba shortly after the capture of Maduro, said he did not think an attack was necessary because "it looks like it's going down."

On Friday, Cuba's Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez declared an "international emergency" in response to the US tariff warning, which he said constituted "an unusual and extraordinary threat."

But the government has said little about how it will manage the growing threat of a humanitarian crisis.

Many of the Cubans Reuters spoke with said daily life—already difficult—had been reduced to basics like assuring food, fuel for cooking, and water, and that it had become noticeably harder in recent days.

Lines for gasoline have grown significantly this week at a handful of service centers in the city still supplied with fuel.

And since the US blocked Venezuelan deliveries of oil to Cuba in mid-December, virtually all gas has been sold at a premium, in dollars—a currency to which few Cubans have access.

'You have to pay the price or stay home.'

The crunch has hit both public and private transportation, putting some buses and private taxis out of business and forcing others to raise their prices.

For decades, the government that has its roots in Fidel Castro's 1959 Cuban Revolution has survived despite sometimes brutal economic struggles, upending regular predictions of imminent collapse or an uprising.

It has long alleged a US-led effort to foment revolt, but the most recent widespread protests were in the pandemic year of 2021, despite a 12% contraction of the economy between 2019 and 2024.

Sharp crackdowns on any form of dissent, combined with the emigration of between one and two million people since the pandemic, have all but eliminated organized in-country opposition.

Meanwhile, Cubans interviewed by Reuters generally declined to answer questions about the prospect of protests.

-

Kim Jong Un's 'reaction' to North Korea embassy 'attack' sparks memes

-

EU halts trade vote: Lawmakers insist US must respect deal in tariff probe limits

-

Elon Musk’s Tesla enters UK power market, aims to supply electricity to homes

-

China passes new ethnic unity law: What it means for minority rights and identity

-

Oil prices surge despite global move to release strategic reserves as geopolitical risks mount

-

US launches new trade probe targeting China, EU and key allies, sparking tariff fears

-

Tornado warning ends for Pittsburgh but tornado watch continues across western Pennsylvania

-

Neil McCasland missing for two weeks as FBI expand search in Albuquerque