History's first pandemic mystery solved after 1,500 years: What really happened?

The discovery reshapes our understanding of how pandemics emerge, recur and spread-and why they remain a persistent feature of human civilization.

Scientists have unraveled a 1,500-year-old puzzle by identifying the cause of the “Plague of Justinian,” the outbreak regarded as the world’s first recorded pandemic.

Researchers have now detected Yersinia pestis in a mass grave beneath the ruins of Jerash in Jordan, marking the first firm biological evidence of the outbreak.

“For centuries we’ve relied on written accounts describing a devastating disease but lacked any hard biological evidence of plague’s presence,” said paper author and genomicist Rays Jiang, of the University of South Florida.

"Our findings provide the missing piece of that puzzle—the first direct genetic window into how this pandemic unfolded at the heart of the empire.”

"The discovery reshapes our understanding of how pandemics emerge, recur, and spread—and why they remain a persistent feature of human civilization."

The researchers further wrote, “Our findings demonstrate that plague pandemics didn’t stem from a single evolutionary lineage or event but instead emerged independently from diverse, regionally entrenched reservoirs.”

How did Yersinia pestis spark a pandemic?

The Justinian Plague, which emerged in 541 CE, is considered the world’s first documented pandemic. It spread rapidly across the eastern Mediterranean and Byzantine Empire, with historians estimating that it claimed between 15 and 100 million lives over two centuries, making it one of history’s most devastating outbreaks.

After centuries of uncertainty, the cause of the Plague has been identified: Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that would later trigger the Black Death in 1346, is believed to have sparked this ancient pandemic.

Cracking a 1,500-year-old medical riddle

The new study uses advanced DNA techniques, led by an interdisciplinary team at the University of South Florida and Florida Atlantic University, and examined eight human teeth recovered from burial chambers beneath Jerash’s ancient Roman hippodrome.

DNA analysis showed that the victims carried nearly identical strains of Y. pestis, confirming the bacterium’s presence in the empire between 550 and 660 AD.

The evidence points to a rapid and lethal outbreak, echoing historical reports of widespread deaths. A separate study indicates that Y. pestis had been circulating in human populations for thousands of years before the Justinian pandemic.

It also suggests that later pandemics, including the Black Death and sporadic cases today, didn’t emerge from a single source but arose independently from animal reservoirs.

-

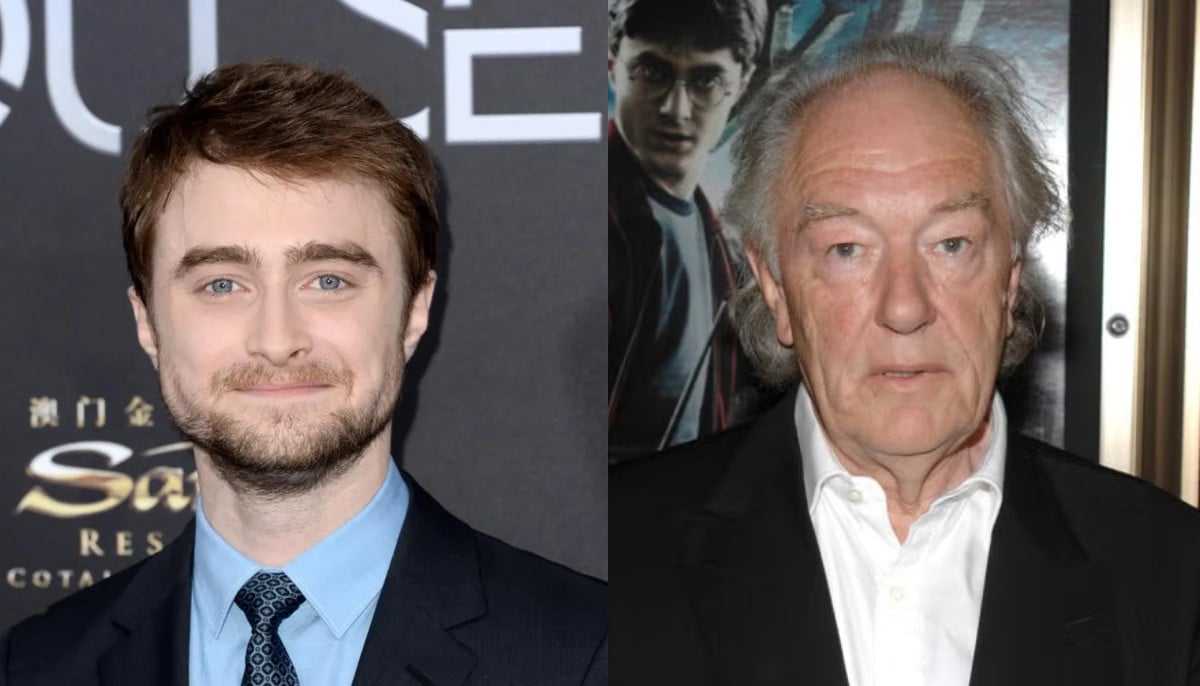

'Harry Potter' alum Daniel Radcliffe gushes about unique work ethic of late co star Michael Gambon

-

Paul McCartney talks 'very emotional' footage of late wife Linda in new doc

-

It's a boy! Luke Combs, wife Nicole welcome third child

-

Gemma Chan reflects on 'difficult subject matter' portrayed in 'Josephine'

-

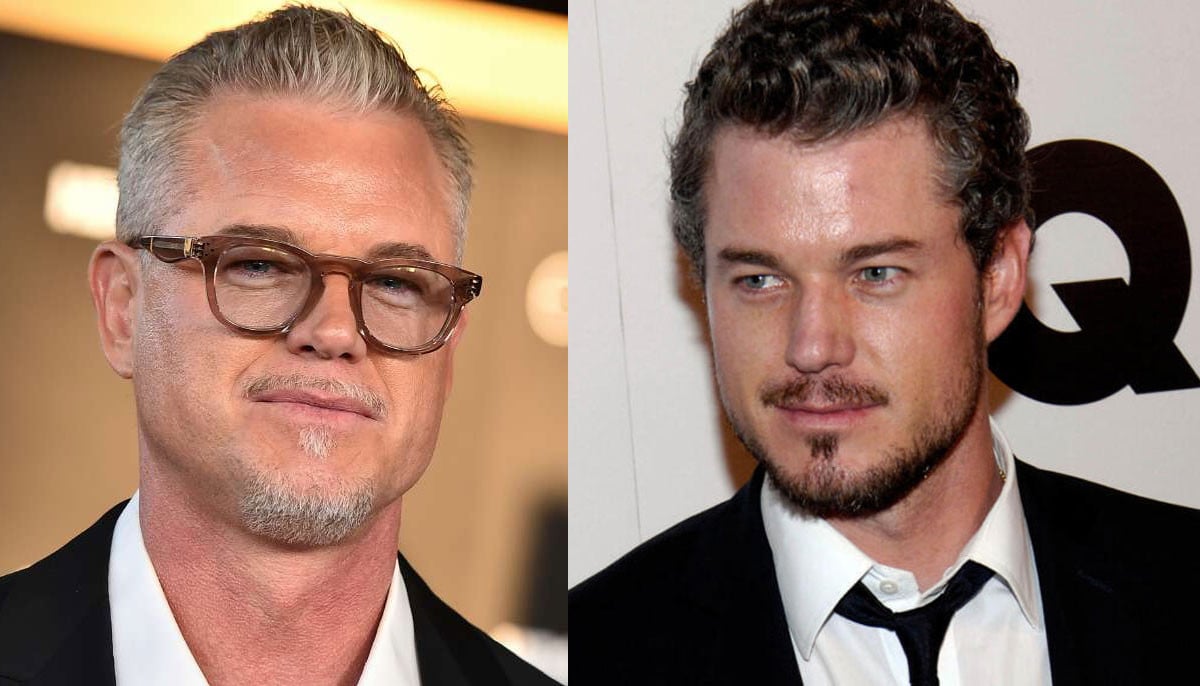

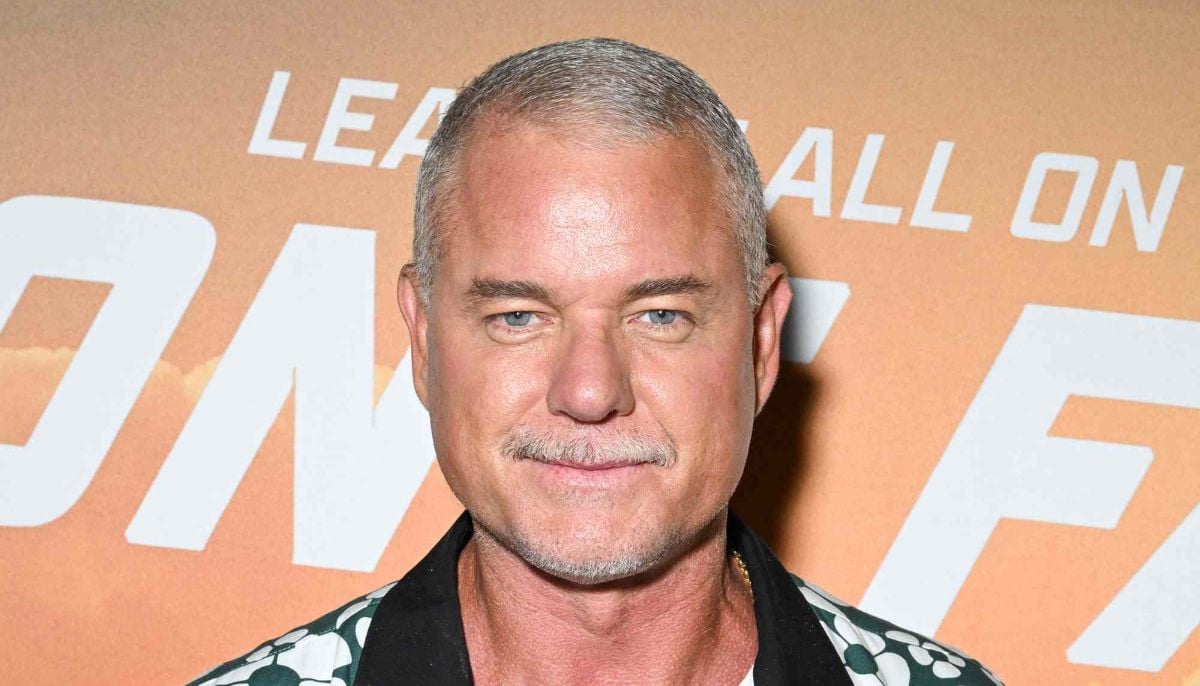

Rebecca Gayheart unveils what actually happened when husband Eric Dane called her to reveal his ALS diagnosis

-

Eric Dane recorded episodes for the third season of 'Euphoria' before his death from ALS complications

-

Jennifer Aniston and Jim Curtis share how they handle relationship conflicts

-

Apple sued over 'child sexual abuse' material stored or shared on iCloud