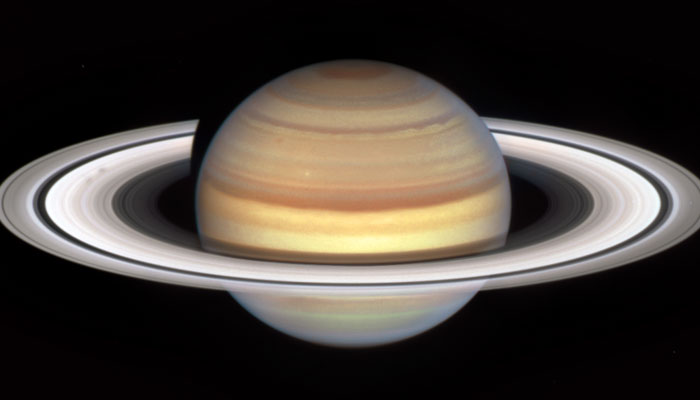

Saturn finally has its first Trojan asteroid

Trojan asteroids are space rocks that share planet's orbit, says scientist

Gaseous giant Saturn seems to have snatched its first known Trojan asteroid “2019 UO14” when the space rock was “bouncing” around the solar system a few thousand years ago.

With the help of this celestial event, Saturn has finally joined its fellow solar system planets as the parent of trailing asteroids called “Trojans”, reported Space.

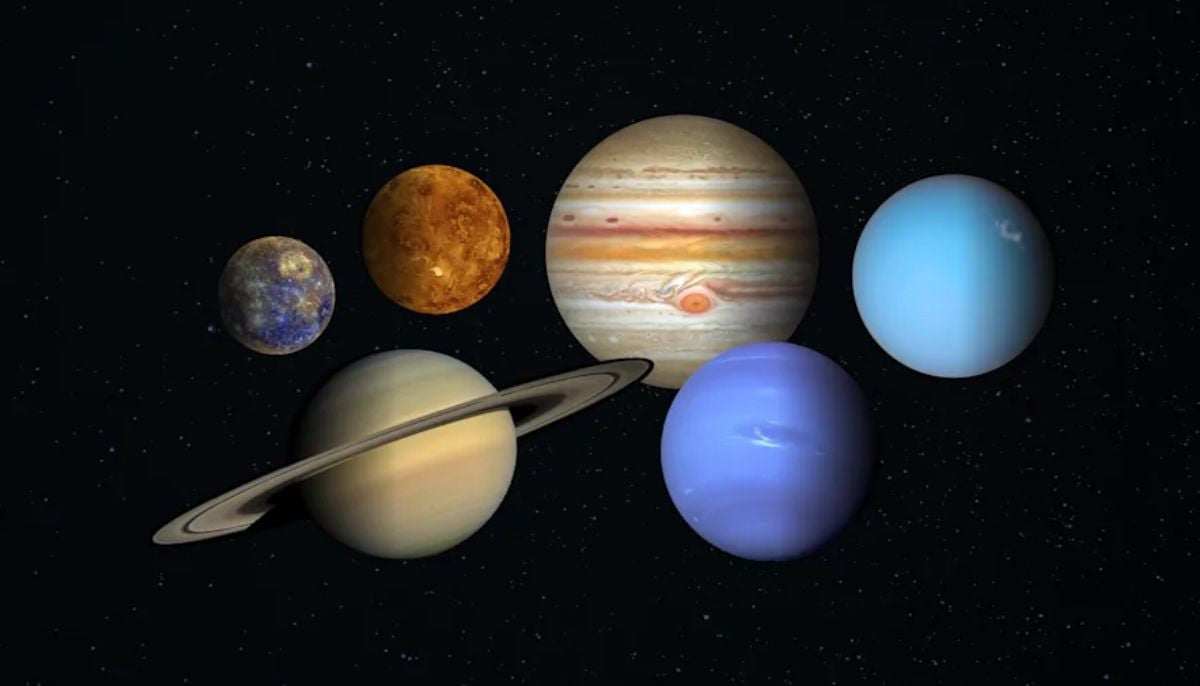

However, it has been revealed that the gas giant may have cheated a little to fit in with its contemporaries, Jupiter, Neptune and Uranus.

As the orbit of this Saturnian Trojan is unstable, Saturn appears to be a terrible parent, which will lose this cosmic hanger-on in around 1,000 years.

This means that astronomers will have to play their part in hunting for more asteroids sharing an orbit with Saturn, especially if the “ringed planet” wants to hang with its fellow gas and ice giants.

It is worth noting that even smaller terrestrial planets like Earth and Mars also have Trojans.

"We think it is about 9 miles (15 kilometres) across, though its composition is unknown, it probably originated from the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune," discovery team member Paul Wiegert said.

He added: "The Trojan asteroid was in the process of gravitationally 'bouncing' between the giant planets when it got snagged by Saturn."

Furthermore, Wiegert explained that Trojan asteroids are space rocks that share a planet's orbit, which is either remaining ahead of or behind the planet.

-

Planetary parade 2026: Here's how to see six planets aligning today

-

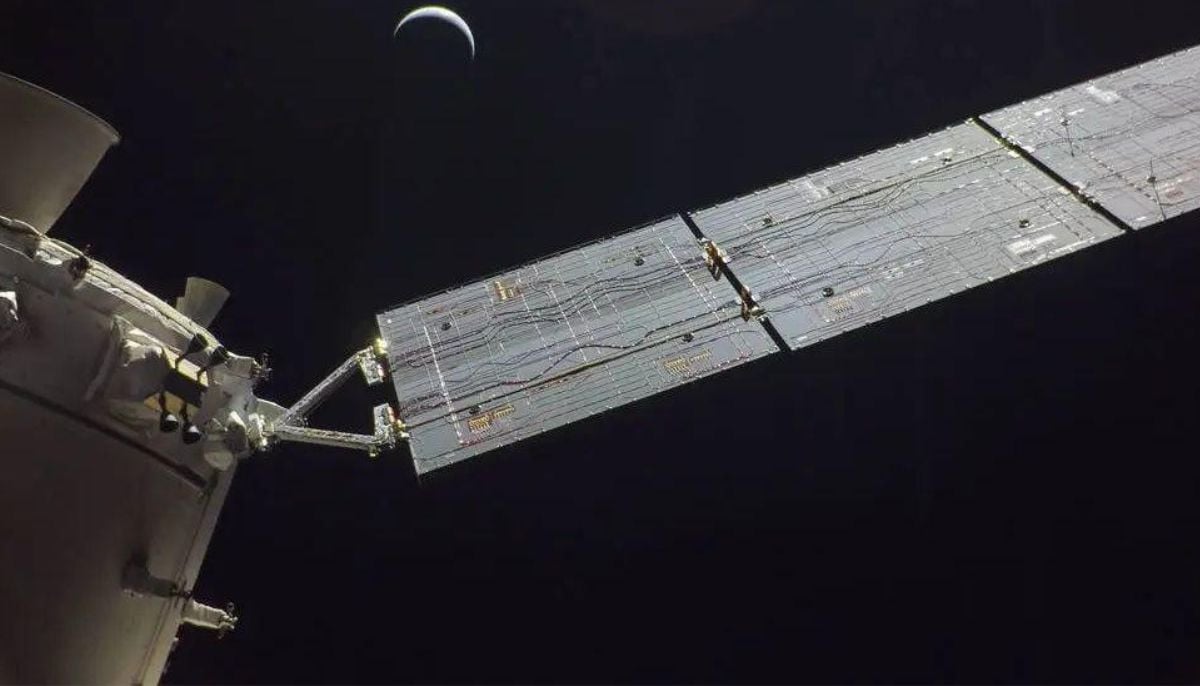

NASA announces new Artemis moon mission aimed at expanding astronauts’ exploration efforts

-

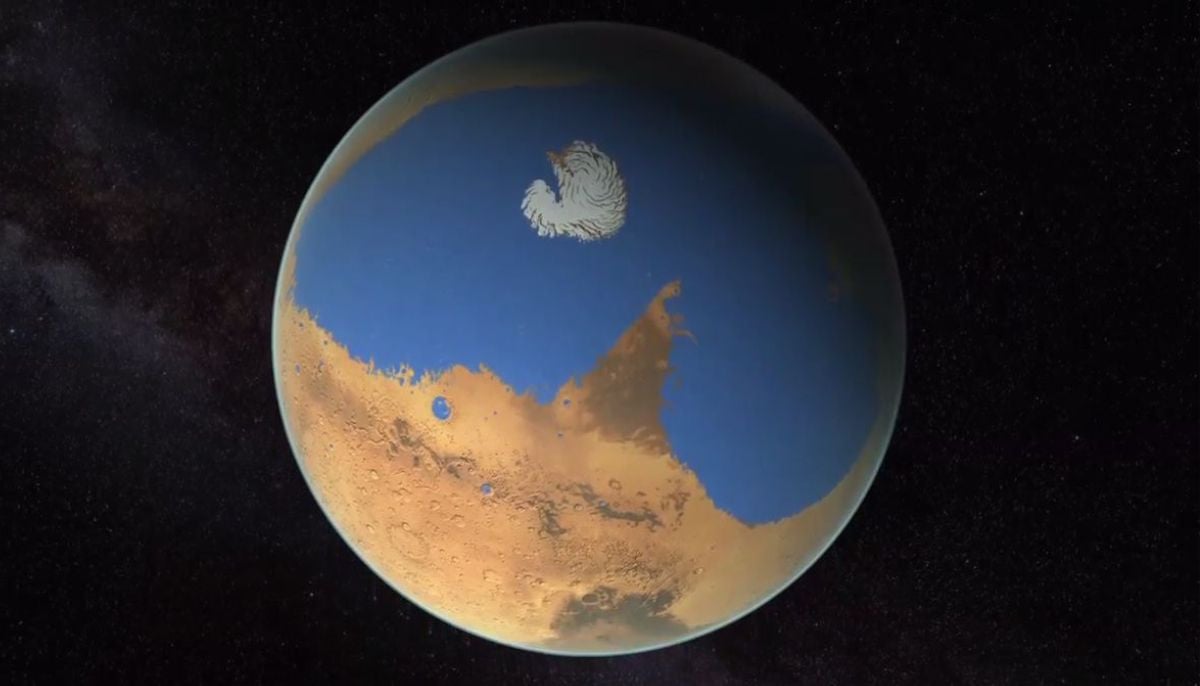

Is human mission to Mars possible in 10 years? Jared Isaacman breaks it down

-

Total lunar eclipse to turn Moon red on March 2-3

-

Stunning new photos of the Milky Way shed light on how stars are formed

-

Antarctica’s mysterious ‘gravity hole’: What’s behind the evolution of Earth’s deep interior?

-

‘Mars’ missing water mystery takes a surprising turn as new study finds regional dust storms trigger massive water loss into space

-

Scientists reveal how sleeping can unlock your creative potential