What do lawyers think of the SC verdict?

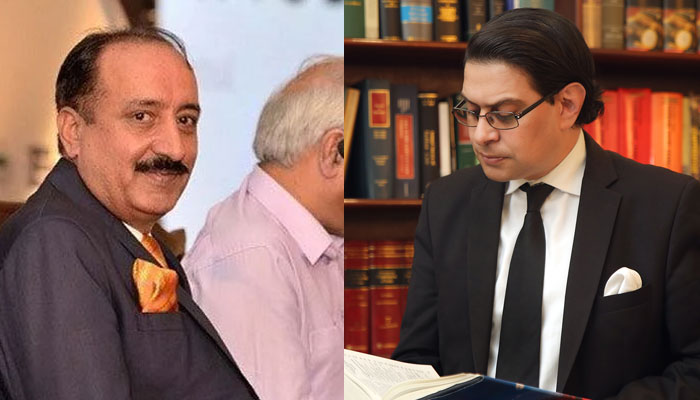

Ahsan Bhoon says that “the dissenting note is closer to the Constitution, in that the majority opinion is an odd interpretation and seems to have added something that was not even in the Constitution

KARACHI: The Supreme Court of Pakistan has ruled — in a 3-2 decision — that the votes of dissident members of parliament, against their parliamentary party’s directives, will not be counted.

With the verdict leading to questions regarding future votes of no-confidence and parliamentarians’ right to vote on individual conscience, lawyers weigh in on the verdict:

President Supreme Court Bar Association Ahsan Bhoon says that “the dissenting note is closer to the Constitution, in that the majority opinion is an odd interpretation and seems to have added something that was not even in the Constitution”.

For lawyer Abdul Moiz Jaferii, “the court in this supposedly robust interpretation has rendered the plain meaning of the Constitution redundant. Article 63-A(2) provides for a process — which the court has simply ignored in favour of a general understanding of disqualification as present in Article 63.

In doing so, it has rendered the idea of deseating — as exemplified in great detail in Article 63-A — completely redundant to suit space for constitutional design. But there is space for constitutional design where the Constitution is not clear — which it is here in 63-A”.

High Court advocate Abuzar Salman Khan Niazi explains the approach taken by the SC: “The court hasn’t done a literal interpretation [of Article 63-A] but has gone for a purposive interpretation in this case. In a kind of activism or judicial lawmaking (which happens around the world), the court has tried to prevent ‘mischief’ by filling in legal loopholes via this verdict. What was the mischief? To prevent ‘lotacracy’. I had personally been erring on the side of a literal interpretation — but there are lawyers who would side with the purposive approach as well”.

Supreme Court lawyer Faisal Chaudhry says that what the SC has done is that it has “in effect kept the background of our floor-crossing and horse-trading in mind — which was the reason for [Article 63-A] in the first place. Our Constitution is different. We have a different political history. In that context, we have to be realistic. Even in this current [political] scenario, the vote of no-confidence wasn’t brought on merit ...but by inducing members of the PTI — who were elected under the PTI ticket. Principally, these members should have resigned and then gone to the public for a fresh mandate”.

Constitutional expert and Supreme Court lawyer Salman Akram Raja says that with this verdict “someone would have to be mad now to vote against the party direction. Not only would the vote not be counted, they could also lose their seat and possibly face jail time. The only door left open for revolt is to convince the majority of party members to vote against their own party leader. The revolt has to be a substantial one — a minority vote will not count”.

Lawyer Salaar Khan says that the court’s opinion “purports to ground itself in democratic principles — and perhaps it is to a fault.

Many wondered whether the court would go to the extent of reading a lifetime disqualification into Article 63-A to prevent it altogether. It’s appreciable that the court didn’t, in this case, go so far as to read in a disqualification period as it has done in the context of 62(1)(f); it left this to parliament.

However, it still effectively reaches the same result through an answer to another question instead — whether or not the vote ought to be counted. Here, the court curiously holds that the ‘true measure’ of the law’s ‘effectiveness’ would be if no person can be a defector to begin with. Now, a dissenting vote will not be counted altogether thus incurring disqualification for no gain. So, to that extent, there’s practically no value left in defecting”. Salaar says that this though “comes at the cost of other provisions of the Constitution which are no less central to a democracy. For instance, in many cases, a vote of no-confidence is now largely redundant”.

On the vote of no-confidence, Faisal Chaudhry feels that it is incorrect to say that the verdict has blocked any chances of a future vote of no-confidence. “The SC has just ensured that you cannot buy votes in parliament. Keeping our political situation before me, I think this is the only way to allow governments to work. The entire decade of the 80s saw vote buying. There’s a very sketchy political background behind 63-A so the SC has successfully filled the loopholes and ensured that the governments are voted out not booted out.”

So how can a vote of no-confidence take place now, after the verdict? Salman Raja says that it can happen “in case of a coalition government or if you get a majority of the parliamentary party to go against their PM. The distinction now is between majority and minority dissent”.

According to legal scholar Osama Siddique: “What the Supreme Court Order doesn’t account for is that political parties are run as fiefdoms or personality cults in Pakistan. What if the party head does egregious things or becomes an erratic and dangerous egomaniac or otherwise undermines democratic principles and norms? What if he then becomes entrenched because of the initial calculus of seats? Is a member then bound to not dissent on essentially national and larger than party considerations?”

Abdul Moiz Jaferii feels the court has also “disregarded the inherent concept of constituency politics or at the very least takes a simplified view of it. A constituency politician is much more than the sum of the parts of his/her political party, and has worked hard to create an individual position.

On the verdict’s expedient nature, Jaferii says: “If you look at the minority opinion, that is where most legal opinion has stood. 63-A says what it says; deseating is deseating — and to read anything else into it is tantamount to adding to the constitution. That is impermissible. The court should also have realized that this reference was tainted with political expediency. Just on that pretext alone this should have been disregarded — just on the timing of the question”.

-

Man Convicted After DNA Links Him To 20-year-old Rape Case

Man Convicted After DNA Links Him To 20-year-old Rape Case -

Royal Expert Shares Update In Kate Middleton's Relationship With Princess Eugenie, Beatrice

Royal Expert Shares Update In Kate Middleton's Relationship With Princess Eugenie, Beatrice -

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Leaves King Charles With No Choice: ‘Its’ Not Business As Usual’

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Leaves King Charles With No Choice: ‘Its’ Not Business As Usual’ -

Dua Lipa Wishes Her 'always And Forever' Callum Turner Happy Birthday

Dua Lipa Wishes Her 'always And Forever' Callum Turner Happy Birthday -

Police Dressed As Money Heist, Captain America Raid Mobile Theft At Carnival

Police Dressed As Money Heist, Captain America Raid Mobile Theft At Carnival -

Winter Olympics 2026: Top Contenders Poised To Win Gold In Women’s Figure Skating

Winter Olympics 2026: Top Contenders Poised To Win Gold In Women’s Figure Skating -

Inside The Moment King Charles Put Prince William In His Place For Speaking Against Andrew

Inside The Moment King Charles Put Prince William In His Place For Speaking Against Andrew -

Will AI Take Your Job After Graduation? Here’s What Research Really Says

Will AI Take Your Job After Graduation? Here’s What Research Really Says -

California Cop Accused Of Using Bogus 911 Calls To Reach Ex-partner

California Cop Accused Of Using Bogus 911 Calls To Reach Ex-partner -

AI Film School Trains Hollywood's Next Generation Of Filmmakers

AI Film School Trains Hollywood's Next Generation Of Filmmakers -

Royal Expert Claims Meghan Markle Is 'running Out Of Friends'

Royal Expert Claims Meghan Markle Is 'running Out Of Friends' -

Bruno Mars' Valentine's Day Surprise Labelled 'classy Promo Move'

Bruno Mars' Valentine's Day Surprise Labelled 'classy Promo Move' -

Ed Sheeran Shares His Trick Of Turning Bad Memories Into Happy Ones

Ed Sheeran Shares His Trick Of Turning Bad Memories Into Happy Ones -

Teyana Taylor Reflects On Her Friendship With Julia Roberts

Teyana Taylor Reflects On Her Friendship With Julia Roberts -

Bright Green Comet C/2024 E1 Nears Closest Approach Before Leaving Solar System

Bright Green Comet C/2024 E1 Nears Closest Approach Before Leaving Solar System -

Meghan Markle Warns Prince Harry As Royal Family Lands In 'biggest Crises' Since Death Of Princess Diana

Meghan Markle Warns Prince Harry As Royal Family Lands In 'biggest Crises' Since Death Of Princess Diana