As a doctrine descends

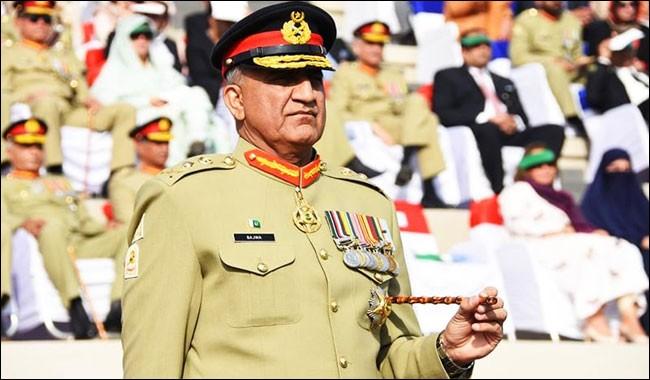

Let’s assume Nawaz Sharif is done and dusted. Is the ‘Bajwa doctrine’ (which has been unloaded upon us in a manner choreographed to seem incidental) capable of leading this country onward and upward?

Conceding that the thought process driving this so-called doctrine reflects a burning personal and institutional desire to make Pakistan a stable, viable and progressive country. The question isn’t one of the bona fides of the underlying intent but of correctness of the thought process. Will the means proposed lead to the desired end?

According to Imtiaz Gul’s account of this (off-the-record?) conversation with journalists, the chief said, “I saved democracy in this country, I’m the biggest supporter of democracy”. As someone wondered on Twitter, saved democracy from whom exactly? Bullet points from the doctrine that solicit comment are: (i) the 18th Amendment was a mistake and needs to be reconsidered; (ii) indiscriminate application of laws anchored in the constitution is a must; and (iii) subversion of the judiciary won’t be tolerated.

Before we consider these points, let’s recall a few fault-lines that have held us up: democracy vs dictatorship; centralism vs federalism; bigotry vs tolerance; representative vs unrepresentative institutions; and doctrine of necessity vs constitutionalism. The civilian-control-of-military camp argues that historically civil-military imbalance in Pakistan has fed centralism, bigotry and doctrine of necessity justifying dictatorships and rule of men. If you stand on the other side of these fault-lines, you seek an end to civ-mil imbalance.

As this conversation is premised on the basis that khakis and civvies all want this country to prosper, this debate isn’t about how best to confine military adventurism to the barracks. So let’s get the awkward bit out of the way. Our history of the constitution being molested and democracy being disrupted is a history of authority being usurped in ‘larger national interest’. All the ‘meray aziz humwatno’ speeches were filled with claims to be serving democracy. This is what makes one nervous about such claims to democracy being or having been saved.

Khurram Husain has written an excellent piece about how NFC formula in the 18th Amendment has given a bigger share of the financial pie to provinces along with a commitment that such share won’t be reduced. This has left less with the centre to commit to defence budget. Is the attack on the 18th Amendment our version of the guns vs butter debate coming to head? Many have warned for years that our national security thinking (and its funding need) isn’t sustainable. Should we reconsider the thinking that makes us a security state or should we wrestle back money committed to people’s welfare in programmes such as BISP?

The ancillary argument is that provinces aren’t yet ready for the power delegated to them and are splurging the cash they’re now awash with. The unstated part of this argument is that post-18th Amendment, the centre has fewer instruments of control over the provinces, which have greater flexibility to do as they please. And this is a bad thing for the country. This is the kind of thinking that broke Pakistan up in 1971. Provinces are underdeveloped – but because they have been kept as such by a paternalistic and overbearing centre.

We are a diverse country. But with Punjab as its largest unit, which naturally dominates all institutions, derisive labels such as ‘Punjabi establishment’ resonate with those in smaller provinces seeking autonomy and empowerment. The 18th Amendment hasn’t transformed us into a confederation. It is step toward realising the constitutional promise that we are a federation. If provinces are to be puppets controlled by a stick-bearing centre, let’s stop pretending that we are a federation or democracy. Allowing agency to provinces is a must for our survival.

For rule of law proponents, there can be nothing more soothing than a chief seeking indiscriminate application of the constitution and the law. Part XII of the constitution deals with the armed forces, and Article 243 states plainly that, “the federal government shall have control and command of the armed forces.” And yet we continue to pretend that the military is a pillar of the state independent of the executive, and ‘doctrines’ appear which nurture the sense that the military is endowed with the power to oversee and keep elected governments in check.

If the wish is to reiterate unflinching commitment to supremacy of the constitution, wouldn’t actions speak louder than words if institutions were seen discharging responsibilities exclusively within their lawful domain? Wherefrom is claimed the legal authority to pontificate on matters that fall way beyond the functions of an institution? Wherefrom is claimed expertise to pronounce upon matters in relation to which one has no training? Would sceptics be wrong in viewing the content of such a ‘doctrine’ as self-contradictory?

And how firm is any professed commitment to indiscriminate application of laws? We have Articles 9, 10 and 10A in the constitution that guarantee right to life and liberty, freedom from illegal detention, due process and fair trial. Now with military courts in place and with the (amended) Anti Terror Act and Fair Trial Act vesting overbroad authority in security agencies, why is the missing person problem still alive and kicking? Why is the Pashtun Long March (or PTM) being painted as anti-Pakistan and Rao Anwar being treated as a pampered son of the soil?

Why is it unpatriotic to question the scope of authority of intelligence agencies or ask why the ISI doesn’t functionally report to the prime minister when the law says it does? When the military pulled itself back from civilian domain post-Musharraf, it was for all to see. The 2013 election didn’t see spooks involved in electoral engineering and credit for that was attributed to General Kayani. Why is the perception growing once again that sector commanders are on the prowl in the run up to Election 2018? And what is being done to dispel it?

Who in his right mind can support subversion of the judiciary? An independent judiciary is essential to uphold rule of law and our collective right to justice. But why was the need felt to declare support for the judiciary? Article 190 of the constitution obliges all executive and judicial authorities to act in aid of the Supreme Court. But when the SC has sought no such assistance and seems perfectly capable of having its orders enforced, why did the leadership of an institution that forms part of the executive volunteer such help and protection?

Justice Shaukat Siddiqui of the Islamabad High Court has been issued a show-cause notice by the Supreme Judicial Council for asking thorny questions about the military’s role as guarantor in the agreement post-Faizabad dharna. The notice states that the judge questioning “participation of officials” in resolution of the Faizabad fiasco “fell outside the judicial domain”. It will be interesting to see the outcome of this reference, as day in and day out judges scrutinise discharge of authority by public officials (who are in civvies of course).

Likewise, a petition against Justice Faez Isa (who as part of the SC bench hearing the Faizabad dharna matter has given grief to intelligence agencies for their sloppy role) is also up for hearing. Now these happenings must be purely coincidental, but they create a perception that so long as the judiciary is rendering judgments against politicos it will be defended and supported. But if judges turn their focus toward exercise of authority by khakis, a consequence could be piercing scrutiny into the conduct of the judges in question.

The basic contradiction underlying a claim to being saviour of democracy and rule of law in this context is: the real source of the power to control the polity from behind the curtain is the threat that if politicos don’t fall in line, direct charge will be taken of the stage. So long as the threat is real, the levers of control are effective. But with such means of control, the state remains unstable and democracy hangs by a thread.

The writer is a lawyer based in Islamabad.

Email: sattar@post.harvard.edu

-

Timothée Chalamet Reveals Rare Impact Of Not Attending Acting School On Career

Timothée Chalamet Reveals Rare Impact Of Not Attending Acting School On Career -

Liza Minnelli Gets Candid About Her Struggles With Substance Abuse Post Death Of Mum Judy Garland

Liza Minnelli Gets Candid About Her Struggles With Substance Abuse Post Death Of Mum Judy Garland -

'Saturday Night Live' Star Will Forte Reveals How He Feels About Returning To The Show After 2010 Exit

'Saturday Night Live' Star Will Forte Reveals How He Feels About Returning To The Show After 2010 Exit -

Police Officer Arrested Over Alleged Assault Hours After Oath-taking

Police Officer Arrested Over Alleged Assault Hours After Oath-taking -

Prince William Issues 'ultimatum' To Queen Camilla As Monarchy Is In 'delicate Phase'

Prince William Issues 'ultimatum' To Queen Camilla As Monarchy Is In 'delicate Phase' -

Maxwell Seeks To Block Further Release Of Epstein Files, Calls Law ‘unconstitutional’

Maxwell Seeks To Block Further Release Of Epstein Files, Calls Law ‘unconstitutional’ -

Winter Olympics 2026: Remembering The Most Unforgettable, Heartwarming Stories

Winter Olympics 2026: Remembering The Most Unforgettable, Heartwarming Stories -

King Charles Hands All Of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Records And Files To Police: Report

King Charles Hands All Of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Records And Files To Police: Report -

Eric Dane's Family Shares Heartbreaking Statement After His Death

Eric Dane's Family Shares Heartbreaking Statement After His Death -

Samsung Brings Perplexity AI To Galaxy S26 With ‘Hey Plex’ Voice Command

Samsung Brings Perplexity AI To Galaxy S26 With ‘Hey Plex’ Voice Command -

Fergie’s Spent £13,000 A Day Since Andrew’s Troubles Started: Here’s Where She Fled

Fergie’s Spent £13,000 A Day Since Andrew’s Troubles Started: Here’s Where She Fled -

Eric Dane's Death Becomes Symbol Of ALS Awareness

Eric Dane's Death Becomes Symbol Of ALS Awareness -

Michael B. Jordan Gives Credit To 'All My Children' For Shaping His Career: 'That Was My Education'

Michael B. Jordan Gives Credit To 'All My Children' For Shaping His Career: 'That Was My Education' -

Sun Appears Spotless For First Time In Four Years, Scientists Report

Sun Appears Spotless For First Time In Four Years, Scientists Report -

Bella Hadid Opens Up About 'invisible Illness'

Bella Hadid Opens Up About 'invisible Illness' -

Lawyer Of Epstein Victims Speaks Out Directly To King Charles, Prince William, Kate Middleton

Lawyer Of Epstein Victims Speaks Out Directly To King Charles, Prince William, Kate Middleton