Governing higher education

Pakistani Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have not produced single Nobel Laureate or unicorn company

Governance is the backbone of any education system. Over the years, I have consistently highlighted the material deficiencies in our educational governance – whether it pertains to basic or higher education.

Reforming governance in universities and HEIs is imperative to raising academic standards, equipping graduates with 21st-century skills, and enhancing research outcomes. Despite significant investments, Pakistan’s HEIs continue to produce subpar results in terms of employable graduates and impactful research. Addressing these systemic weaknesses through comprehensive governance reforms, inspired by global best practices, is the way forward.

The governance structures in Pakistan’s public-sector HEIs are outdated, marked by huge inefficiencies, poor outcomes, and a lack of accountability. One critical reform is transforming governing boards to enhance their effectiveness. A major improvement is needed in their composition. The majority of the governing boards should comprise independent, non-executive members with expertise in fields such as education, finance, law, technology, and governance practices. Appointments should be merit-based, ensuring diverse perspectives and a strong commitment to institutional progress.

Top global universities, such as those in the Ivy League, Stanford, MIT, and leading institutions in the UK like Oxford and Cambridge, have consistently produced remarkable contributions to both scientific advancements and entrepreneurship. These institutions are home to hundreds of Nobel Laureates and have generated alumni who founded thousands of billion-dollar companies, such as Google, Facebook, and Microsoft. Their emphasis on research, innovation, and robust governance frameworks has enabled them to shape the modern world.

In stark contrast, Pakistani Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have not produced a single Nobel Laureate or unicorn company, underscoring the urgent need for transformative reforms to build an ecosystem capable of fostering world-class scientists and entrepreneurs.

To strengthen board governance, subcommittees focused on key areas like finance, audit, academics, and research should be established. These subcommittees can streamline oversight functions, facilitate evidence-based decision-making, and enable boards to focus on strategic priorities.

Another essential reform is the separation of roles between the governing board’s chairperson and the vice-chancellor (VC). Currently, VCs serve as both the chief executive and the chairperson of governing boards, creating a conflict of interest that compromises the independence of the boards. This dual responsibility hampers independent oversight. The governing board should instead be chaired by an independent, non-executive member, while the VC focuses on implementing strategies approved by the board and managing day-to-day operations. This separation of powers will ensure robust governance.

VCs should be selected for their leadership, strategic acumen, and management expertise, rather than being solely evaluated on academic credentials like a PhD or publication count, and the chairperson of the board should have governance experience.

One of the biggest weaknesses in the current governance frameworks of almost all public-sector HEIs is that the power of appointment and termination of VCs is vested in the prime minister/president in the case of federal HEIs and chief minister in the case of provincial HEIs for the tenure of three to four years. Since prime ministers and chief ministers have huge responsibilities managing the country and provinces and do not provide any oversight on HEIs, this results in a major flaw that breaks down board governance. It is therefore essential that this power of appointment or removal of the CEO, which is inherently vested in the board in almost all jurisdictions, must be changed to empower the governing boards.

To institutionalise good governance practices, the Higher Education Commission (HEC) should develop a governance code for HEIs. This code should be modeled on the State-Owned Enterprises (SOE) Act 2023 and global best practices. It should clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the governing board, chairperson and VC. It should also empower the boards to appoint the VCs, mandate annual evaluations of board performance, and require external auditors to review compliance with the code.

Financial accountability is another critical area for reform. HEIs must prepare financial statements under recognised frameworks, such as the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), and ensure they are independently audited according to International Standards on Auditing (ISA) as applicable in Pakistan. Transparency in financial practices will build trust among stakeholders and ensure effective utilisation of public and private investments in education. Annual reports detailing financial performance, academic achievements and research contributions should be made publicly available on HEIs’ websites.

Periodic external assessments of HEIs are necessary to evaluate their outcomes relative to investments. Metrics such as graduate employability, research quality, and operational efficiency should guide these assessments, fostering accountability and identifying areas for improvement.

Another pressing need is to establish a unified higher education governance structure that promotes collaboration between federal and provincial governments. The current setup – with separate federal and provincial HECs alongside provincial education departments – results in duplication, inefficiencies, and inconsistent policies. A single, unified Higher Education Commission, with representation from federal and provincial governments as well as independent, non-executive members, can address these issues. Such a body would ensure cohesive policymaking, regulate HEIs effectively, and align national priorities with global standards.

HEIs must also embrace digital transformation to modernise their operations and improve outcomes. By automating administrative processes, implementing robust e-learning platforms, and leveraging data analytics, institutions can become more efficient and accessible. Online and hybrid learning models should be normalised to expand access to education and enable lifelong learning. With focused leadership, a two-year timeline for digital transformation is achievable.

Public-private partnerships offer significant opportunities to improve funding and strengthen industry linkages. Such collaborations can establish innovation hubs, co-fund research, and provide students with practical workplace exposure. Engaging industry in curriculum design and skill development will ensure graduates are well-prepared for job markets.

Leadership development is another cornerstone of effective governance. Board members, VCs and other executives should undergo regular training in governance, strategic planning, and performance evaluation. Leadership development programmes can build the capacity of HEI leaders to tackle challenges and drive institutional growth.

Specific focus should also be given to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education and entrepreneurship. Establishing specialised research centres, innovation labs, and incubators within HEIs can provide a platform for groundbreaking research and startup development. These initiatives should be integrated into academic curricula to foster an entrepreneurial mindset among students and faculty. It is important that leadership in research, startup development and incubators is entrusted to individuals with the right mindset. Partnerships with top global companies and universities should also be cultivated to enhance the quality of these initiatives and provide students with access to cutting-edge technologies and opportunities.

These reforms are not theoretical ideals; they are grounded in proven practices adopted by leading universities worldwide. Countries like the US and the UK have successfully implemented governance frameworks that emphasize independent boards, financial transparency, and strong leadership. Pakistan’s HEIs can draw inspiration from these examples to build a robust higher education system.

The stakes could not be higher. The low quality of human resources in Pakistan, driven by an archaic and ineffective education system, is a major factor behind the country’s socio-economic problems. Reforming HEIs can serve as a catalyst for national progress by producing skilled graduates and impactful research that addresses business and societal needs.

By implementing these reforms, Pakistan can transform its higher education institutions into global centers of learning and innovation. Improved governance, financial transparency and digital adoption will enable HEIs to contribute meaningfully to the nation’s development and prepare graduates to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

The writer is a former managing partner of a leading professional services firm and has done extensive work on governance in the public and private sectors. He tweets/posts @Asad_Ashah

-

Costco Canada Food Court’s New Menu Item Sparks Debate: 'Take This Back!'

Costco Canada Food Court’s New Menu Item Sparks Debate: 'Take This Back!' -

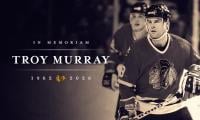

Chicago Blackhawks Honour Troy Murray With Tribute And Moment Of Silence At United Center

Chicago Blackhawks Honour Troy Murray With Tribute And Moment Of Silence At United Center -

Washington Capitals Rout Calgary Flames 7-3 Behind Connor McMichael's Two Goals

Washington Capitals Rout Calgary Flames 7-3 Behind Connor McMichael's Two Goals -

Fact Check: Iddo Netanyahu’s Death Rumours Spread Online But Viral Fire Video Comes From New Jersey

Fact Check: Iddo Netanyahu’s Death Rumours Spread Online But Viral Fire Video Comes From New Jersey -

Hilary Duff Says She And Sister Haylie Duff ‘don’t Speak’ Right Now

Hilary Duff Says She And Sister Haylie Duff ‘don’t Speak’ Right Now -

Steve Carell Reveals Role That Means Most To Him

Steve Carell Reveals Role That Means Most To Him -

Prince William, Harry Relationship Turning Point Came In 2020, Says Insider

Prince William, Harry Relationship Turning Point Came In 2020, Says Insider -

Harry Styles Reveals Why He Became More Private After 'One Direction' Split

Harry Styles Reveals Why He Became More Private After 'One Direction' Split -

Eva Mendes Shares Behind-the-scenes Glam Prep Before Ryan Gosling’s SNL Hosting Gig

Eva Mendes Shares Behind-the-scenes Glam Prep Before Ryan Gosling’s SNL Hosting Gig -

King Charles Stable As New Poll Says Monarchy Will Last 20 More Years

King Charles Stable As New Poll Says Monarchy Will Last 20 More Years -

John F. Kennedy Jr.'s Ex Daryl Hannah's Pal Rosanna Arquette Slams 'Love Story' Portrayal

John F. Kennedy Jr.'s Ex Daryl Hannah's Pal Rosanna Arquette Slams 'Love Story' Portrayal -

Bianca Censori's Plan To Expose Kanye West Revealed

Bianca Censori's Plan To Expose Kanye West Revealed -

Princess Diana Disliked Woman Who ‘really Understood’ King Charles

Princess Diana Disliked Woman Who ‘really Understood’ King Charles -

Tori Spelling Reacts To Online Rumors About Her Appearance: 'It’s Horrific'

Tori Spelling Reacts To Online Rumors About Her Appearance: 'It’s Horrific' -

Arnold Schwarzenegger 'in Talks' For Potential Return To Iconic ’80s Roles

Arnold Schwarzenegger 'in Talks' For Potential Return To Iconic ’80s Roles -

Oil Crisis: Saudi Cuts Oil Output As Prices Hit Highest Since 2022; G7 Weighs Stock Release

Oil Crisis: Saudi Cuts Oil Output As Prices Hit Highest Since 2022; G7 Weighs Stock Release