The Daanish debate

Whether the Daanish Schools effort has been able to live up to its principles or not may be debatable

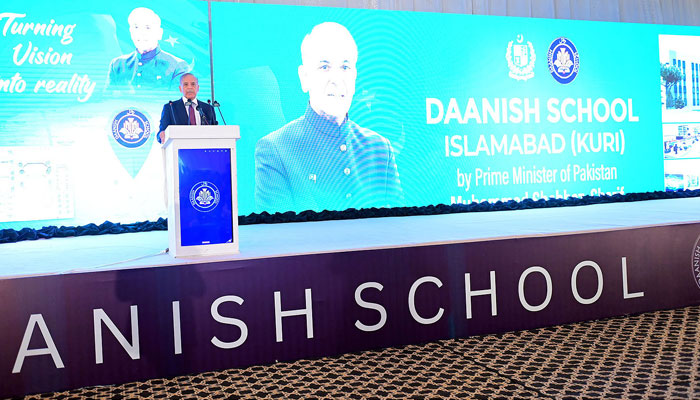

On April 9, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif inaugurated a Daanish School campus in Islamabad. The Daanish Schools effort is anchored in a powerful principle: every child should be able to access the highest quality education. Whether the Daanish Schools effort has been able to live up to its principles or not may be debatable, but many experts that I respect deeply take issue with the principle itself. This is a problem with many dimensions and implications.

Resource constraints are the most common citation against Daanish Schools. One of my dear friends – politically unattached, and intellectually courageous – said in response to the April 9 launch in Islamabad, that many, many regular government schools could be built in the amount of money that it will take to build one Daanish school. She isn’t wrong – Daanish schools are indeed very expensive.

Yet schools – subsidized entirely by the state – for gifted and talented students exist in almost any country where it is not a curse to be born underprivileged. Should gifted and talented children on the wrong side of DHA be excluded from access to high-quality education just because of the circumstances of their birth? Of course not.

Perhaps the debate around Daanish schools should then be about how the Pakistani governance system determines and decides which gifted and talented students will have access to a Daanish school, and how the quality of the learning experience at Daanish schools will be established and maintained.

Sadly, as I explained in this column last week, much the way that the NFC debate is centred around the wrong metric and the wrong incentive (a fiscal crisis), the Daanish school debate is centred around the wrong person and the wrong instinct. Most of the negative reaction to Daanish schools among experts and genuine critics is anchored, wittingly or unwittingly, around the person of the prime minister. If we don’t like Shehbaz Sharif, we naturally will not be open to liking anything he does.

My challenge is the opposite. Being partial to the kind of obsessive work ethic and appetite for delivery that the current PM has demonstrated, I need to establish an objective view of public policy efforts like the Daanish schools. Additionally, as a trusted voice and often an adviser to governments and international organizations, my perspective on Daanish schools needs to be consistent with the wider philosophy I espouse in education, and my positions on an array of other, relevant and related public policy issues.

What should the primary metric for assessing Daanish schools be? First, let’s get rid of the branding – for the sake of objectivity. ‘These’ schools are supposed to be premium quality government schools for capable students from the most underprivileged circumstances. The schools are publicly funded and are capital-intensive, but this is a modality of how these schools are delivered. It is not germane to the purpose of establishing and running them.

The primary purpose of these schools is not how cheaply or efficiently they can be run. The primary purpose of these schools is to ‘level up’ children who would otherwise have no route to a better life. The means of achieving this purpose is through the provision of a world-class learning experience for these poor kids – absent the burden of economic, social, opportunity, or other kinds of costs. These schools are the delivery instrument for this ‘world-class learning experience’. The first-order question about these schools then should be: ‘Are these schools providing a world-class learning experience?’

Instead of this line of questioning, critics of these schools jump ahead to the more mundane, but more readily ‘viral’ question of costs and financing. The issue of the costs of building these schools, and running these schools is important if your job is to track public expenditure. It is also important if you have a generic scepticism of all government spending. It is also important if you believe that all politicians and bureaucrats are corrupt and all money in the public sector is vulnerable to being stolen. The issue of the costs of building these schools and running these schools, however, is not more important than the quality of learning experience being provided at, or the end product graduating from these schools.

This doesn’t mean that the quantum of expenditure on these schools does not merit serious scrutiny or reflection. But it does mean that the key metric for assessing whether this is a good idea and whether it is working needs to be the purpose for which the idea was conceived and executed.

Here, the Punjab Daanish Schools and Centers of Excellence Authority Act of 2010 becomes instructive. This is the law through which the Daanish schools were codified as part of the law. This law offers a keen insight into the structural inclinations and habits of the Pakistani public sector. And it merits deep reflection as the current prime minister tries to fulfil his well-founded and important passion for high-quality education.

If you read through the law, two things will strike you powerfully. One is obvious (and inspiring and noble). The other is invisible, requires objective scrutiny and is worrying.

First, the good news. The law clearly articulates who the Daanish schools are for. In its own words, they are for “the destitute, most deprived and marginalized student, if the total combined gross income of the members of the household of the student does not exceed six thousand rupees per month.” Over the years, this baseline income level has increased to Rs15,000 – but the principle this stipulation espouses is absolutely one that should excite and engage every reasonable Pakistani.

Now the bad news. The word ‘excellence’ appears in the law fourteen times but is capitalized in each instance. It refers to the “Centres of Excellence” that the law is authorizing. Not once in the entire law is the notion of excellence unpacked or defined. We can’t know what quality education Daanish schools are providing if the law itself doesn’t commit to that quality. Speaking of which, the word ‘quality’ appears three times in the law. Again, there too, the word is not defined. We don’t know what the law intended when it articulated its commitment to quality.

The Daanish schools law is an ample case study of how the framing of really high quality (no pun intended) public policy instincts results in amorphous public policy results. Daanish schools have been in operation for over a decade. The core instinct of PM Shehbaz Sharif in initiating these schools was noble, righteous, and urgent – then as it remains now. The core instinct of critics of these schools in questioning the per unit cost of delivering high-quality education, synonymous with ‘excellence’, is misguided and off the mark.

The reason is that neither the law that established Daanish schools itself nor the critics of the effort are focusing on the core purpose of the schools – a life-altering, path-breaking and globally competitive, premium quality education.

On April 9, at the inauguration of the Daanish school in Islamabad, PM Shehbaz Sharif renewed his long-standing commitment to education by responding to the calls for a robust and concerted effort to address the massive learning crisis in the country – one that is reflected in part in the large numbers of out of school children. Federal Minister for Education Dr Khalid Maqbool Siddiqui also spoke at the event of the urgency of taking action on this front. His delivery was passionate and reflective of a degree of sincerity. All of this is welcome. It is exciting news for those invested in education.

The real question in all this – be it Daanish schools, or of convening the Council of Common Interests to establish a national agenda for education, or of finding more efficient ways to deliver education, or of school meals programmes, or the vitality of government school buildings as centres of convening communities around the country – is what the purpose of all of it is.

If Pakistani children do not learn they will not prosper. An education system (public and private) cannot only serve the needs of teachers, consultants, bureaucrats, or private school owners. An education system – and all efforts to improve it – must be for the children that the system claims to be serving. The metric for this service is learning. It is excellence. It is quality. If we aren’t talking about learning, the quality of teaching, and what constitutes excellence, we are repeating mistakes we have already made.

The writer is an analyst and commentator.

-

Pamela Anderson, David Hasselhoff's Return To Reimagined Version Of 'Baywatch' Confirmed By Star

Pamela Anderson, David Hasselhoff's Return To Reimagined Version Of 'Baywatch' Confirmed By Star -

Willie Colón, Salsa Legend, Dies At 75

Willie Colón, Salsa Legend, Dies At 75 -

Prince Edward Praised After Andrew's Arrest: 'Scandal-free Brother'

Prince Edward Praised After Andrew's Arrest: 'Scandal-free Brother' -

Shawn Levy Recalls Learning Key Comedy Tactic In 'The Pink Panther'

Shawn Levy Recalls Learning Key Comedy Tactic In 'The Pink Panther' -

King Charles Fears More Trouble As Monarchy Faces Growing Pressure

King Charles Fears More Trouble As Monarchy Faces Growing Pressure -

Inside Channing Tatum's Red Carpet Return After Shoulder Surgery

Inside Channing Tatum's Red Carpet Return After Shoulder Surgery -

Ryan Coogler Brands 'When Harry Met Sally' His Most Favourite Rom Com While Discussing Love For Verstality

Ryan Coogler Brands 'When Harry Met Sally' His Most Favourite Rom Com While Discussing Love For Verstality -

Sarah Pidgeon Explains Key To Portraying Carolyn Bessette Kennedy

Sarah Pidgeon Explains Key To Portraying Carolyn Bessette Kennedy -

Justin Bieber Rocked The World With Bold Move 15 Years Ago

Justin Bieber Rocked The World With Bold Move 15 Years Ago -

Sam Levinson Wins Hearts With Huge Donation To Eric Dane GoFundMe

Sam Levinson Wins Hearts With Huge Donation To Eric Dane GoFundMe -

Kate Middleton Steps Out First Time Since Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor's Arrest

Kate Middleton Steps Out First Time Since Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor's Arrest -

Inside Nicole 'Snooki' Polizzi's 'private' Marriage With Husband Jionni LaValle Amid Health Scare

Inside Nicole 'Snooki' Polizzi's 'private' Marriage With Husband Jionni LaValle Amid Health Scare -

Germany’s Ruling Coalition Backs Social Media Ban For Children Under 14

Germany’s Ruling Coalition Backs Social Media Ban For Children Under 14 -

Meghan Markle Shuts Down Harry’s Hopes Of Reconnecting With ‘disgraced’ Uncle

Meghan Markle Shuts Down Harry’s Hopes Of Reconnecting With ‘disgraced’ Uncle -

Liza Minnelli Alleges She Was Ordered To Use Wheelchair At 2022 Academy Awards

Liza Minnelli Alleges She Was Ordered To Use Wheelchair At 2022 Academy Awards -

Quinton Aaron Reveals Why He Does Not Want To Speak To Wife Margarita Ever Again

Quinton Aaron Reveals Why He Does Not Want To Speak To Wife Margarita Ever Again