Fallacious utopia

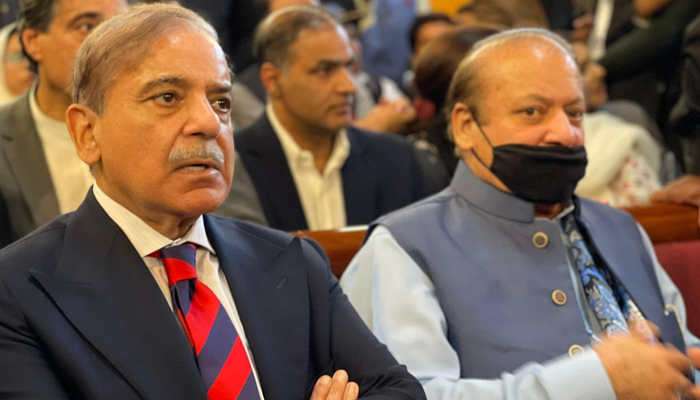

As the country witnessed a rather emotional return of the bastion of the House of Sharif, a pressing question remains regarding the future outlook of leaders to come.

While the country is scheduled to undergo a programme of economic recovery, are we to remain dependent on the exile and return of leaders for the country to function?

In one of his popular dialogues – the ‘Republic’ – Plato presents the framework of a just society. As loaded as this term may be, one of the key features of this society was the presence of a ‘philosopher king.’ An individual who governs his subjects and his own life in the course of pursuing the ultimate truth and thereby discovering that notion of good which encompasses justice, equity, and equality.

Plato argues that such a figure would be suited to the role of a leader as his spirit would not be encumbered by greed and lust which are traits of human beings found in a state of nature (ie: people left without a state or collective union). Plato’s assumption is that the absence of political ambition would allow the philosopher to enact policies beneficial for his subjects. Without delving into the merits of Plato’s arguments in this dialogue, the question remains whether such a figure could be allowed to emerge from amongst the 230 million people residing in Pakistan.

It appeared for a moment that former prime minister Imran Khan might represent the stoic ideals encapsulated in Plato’s philosopher. Placed into that coveted throne was a man who preached ideals of morality by rinsing the corridors and halls of parliament. As many of his cultists argue, he had ‘nothing to gain’ from coming to Pakistan and contesting elections to become the leader of this great nation. Before his ardent supporters give out a yelp of excitement over this dignified allusion to the selfless king, it is worth noting that Mr Khan was operating in a vacuum, divorced from the practical realities under which he had been anointed as leader by the forces that be.

The abrupt divorce between Islamabad and Rawalpindi towards the end of Mr Khan’s premiership signalled his amnesia of how his coronation was arranged. It seemed that pride, vainglory, and hastiness trumped the pursuit of justice. Slogans were thrown around, claims were made, members of the opposition eliminated; what started as a programme of accountability, remained just that – a programme. To what end, no one knows, nor did anyone care. As long as petrol prices remained low, the thieves in their cells, and inflated figures of GDP growth were provided, we stood at the cusp of greatness. The wheel continued to rotate, rather than being re-imagined.

One may approach the subject of Mr Nawaz Sharif’s return with similar scepticism due to his turbulent tenures as prime minister: an inevitable tussle with the not-so smooth operators leading to his court trial and subsequent dismissal. At Minar-e-Pakistan we witnessed a somewhat emotional Nawaz Sharif, a father returning to his children after a journey through time. However, Mr Sharif may not have noticed that the younger of the bunch may no longer be willing to welcome him with open arms as long as their treasured chief remains in Adiala Jail.

The subtle difference that is always associated with the love of the people for their leader lies within the fear or generosity of the said leader. As of now, the gems of history have been presented before us. However, the episodes of disqualification and the move to London has left the populace feeling uneasy.

With the ushering of each leader, a different dream was sold to the public. Upon partition, it was that we are free from the persecution and tyranny of our neighbours; Pakistan then became a treasured ally of the West, we were the last stronghold in Asia against the communist wave; our nation bore the brunt of the war on terror, lives were lost and we were told that it was for the greater good; then we cosied up to our Chinese benefactors so that a program of economic mobilization was initiated; and now we yearn for true freedom.

It appears that we have come full circle, now that once again freedom is being demanded, but freedom from what or whom. Freedom from our circumstances, freedom from our declining status, or freedom from those who represent our interests? The preceding three demands represent the ambivalence of feelings amongst the interests of people along a polarized spectrum of socio-economic classes.

Unfortunately, the arrival at ballot-boxes has always been a dilemma of choosing between the lesser of evils for many of those reading this article. Could it be that our political environment has never been conducive to the grooming of potential philosopher kings or that the divide between the two classes that exist – oligarchs and workers – has enlarged to the extent that the only option that remains is tyranny? Policies have been made as part of knee-jerk reactions to various local and international plights, without the foresight of future repercussions. A reflection on our political history would reflect that it has been a case of both illnesses.

As rebellious children, we ask rather rudely: what has this 75-year-old state provided us? Broken dreams and broken people. While ambassadors were being driven across the border, our dictators and politicians were concerned with the acquisition of marvels of German and Japanese engineering. As a piece of our country broke away, our president was recovering from his stupor in the early hours of the morning.

Finally, as accountability and justice was being delivered, disputes over a bureaucratic appointment translated into a swift ejection from parliament. It appears that Pakistan may not be capable of producing philosopher kings. However, one could argue that it simply requires an immediate cessation of prodigal habits to favour gradual cultivation of empathetic leaders.

The writer is a lawyer.

-

King Charles Lands In The Line Of Fire Because Of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor

King Charles Lands In The Line Of Fire Because Of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor -

Denise Richards Doubles Down On Abuse Claims Against Ex Husband Aaron Phypers Amid Show Return

Denise Richards Doubles Down On Abuse Claims Against Ex Husband Aaron Phypers Amid Show Return -

Russia Set To Block Overseas Crypto Exchanges In Sweeping Crackdown

Russia Set To Block Overseas Crypto Exchanges In Sweeping Crackdown -

Gwyneth Paltrow Reveals Deep Personal Connection With Kate Hudson

Gwyneth Paltrow Reveals Deep Personal Connection With Kate Hudson -

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle’s Game Plan For Beatrice, Eugenie: ‘Extra Popcorn For This Disaster’

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle’s Game Plan For Beatrice, Eugenie: ‘Extra Popcorn For This Disaster’ -

OpenAI To Rollout AI Powered Smart Speakers By 2027

OpenAI To Rollout AI Powered Smart Speakers By 2027 -

Is Dakota Johnsons Dating Younger Pop Star After Breakup With Coldplay Frontman Chris Martin?

Is Dakota Johnsons Dating Younger Pop Star After Breakup With Coldplay Frontman Chris Martin? -

Hilary Duff Tears Up Talking About Estranged Sister Haylie Duff

Hilary Duff Tears Up Talking About Estranged Sister Haylie Duff -

US Supreme Court Strikes Down Trump’s Global Tariffs As 'unlawful'

US Supreme Court Strikes Down Trump’s Global Tariffs As 'unlawful' -

Kelly Clarkson Explains Decision To Quit 'The Kelly Clarkson Show'

Kelly Clarkson Explains Decision To Quit 'The Kelly Clarkson Show' -

Inside Hilary Duff's Supportive Marriage With Husband Matthew Koma Amid New Album Release

Inside Hilary Duff's Supportive Marriage With Husband Matthew Koma Amid New Album Release -

Daniel Radcliffe Admits To Being Self Conscious While Filming 'Harry Potter' In Late Teens

Daniel Radcliffe Admits To Being Self Conscious While Filming 'Harry Potter' In Late Teens -

Director Beth De Araujo Alludes To Andrew's Arrest During Child Trauma Talk

Director Beth De Araujo Alludes To Andrew's Arrest During Child Trauma Talk -

'Harry Potter' Alum Daniel Radcliffe Gushes About Unique Work Ethic Of Late Co Star Michael Gambon

'Harry Potter' Alum Daniel Radcliffe Gushes About Unique Work Ethic Of Late Co Star Michael Gambon -

Video Of Andrew 'consoling' Eugenie Resurfaces After Release From Police Custody

Video Of Andrew 'consoling' Eugenie Resurfaces After Release From Police Custody -

Japan: PM Takaichi Flags China ‘Coercion,’ Pledges Defence Security Overhaul

Japan: PM Takaichi Flags China ‘Coercion,’ Pledges Defence Security Overhaul